silver, print, photography

#

portrait

#

light pencil work

#

16_19th-century

#

character portrait

#

silver

#

wedding photograph

# print

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

photography

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

england

#

surrealism

#

men

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

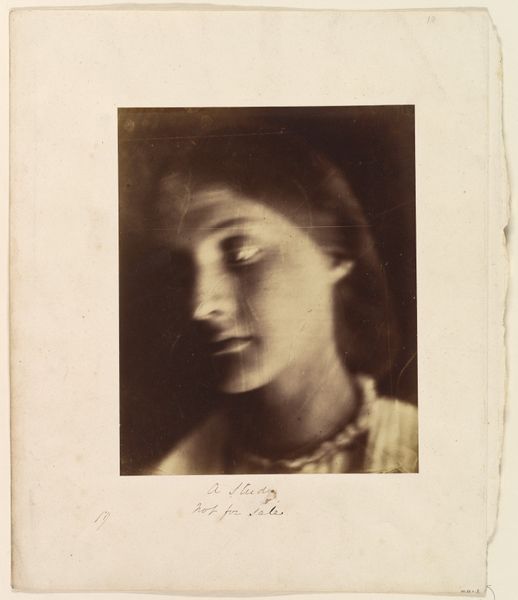

Dimensions: 24.5 × 19.1 cm (image/paper); 28.1 × 18.5 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Here we have Julia Margaret Cameron's "Julia Jackson," a silver print made between 1864 and 1865. Editor: It's immediately striking—so soft, almost dreamlike. The lighting, a play of chiaroscuro, draws your eye straight to the face. There's a definite Romantic sensibility. Curator: Cameron, of course, deliberately employed a soft-focus technique, challenging conventional photographic precision. Note how the composition hinges on the tonal relationships; light isn't just revealing form, it is form. Semiotically, the fuzziness evokes a kind of ethereal presence. Editor: Yes, and contextually, we can understand this rejection of crispness as a move against the clinical realism photography was often associated with at the time. Photography during the Victorian era, especially portraiture, was really becoming democratized—accessible to the rising middle classes. But Cameron elevated it. Curator: Indeed. The textured interplay of light and shadow, seen formally, provides an insight into Cameron’s intentional pursuit of atmospheric effect, making tangible a very palpable but indefinite mood. Her work explores the potential for the camera to access emotional states. Editor: Consider also the sitter herself. Julia Jackson, who would become Virginia Woolf's mother. As a member of the intellectual elite, Jackson, in front of Cameron’s lens, actively participates in creating an image of thoughtful contemplation, reflecting Victorian ideals of feminine intelligence and inner life, yet also pushing against constraints. The portrait thus enters discourses about gender roles and female agency. Curator: And look at the almost painterly manipulation of the print itself. There's an undeniable materiality that reminds us this isn't just a mechanical reproduction, but a constructed image. The subtle gradations speak of careful attention to detail. Editor: Seeing Cameron's images within a gallery space invites critical considerations about display and historical framing. Are we viewing these portraits as records of notable figures, or as conscious artistic interventions that question the very nature of photographic truth? It becomes less about Jackson's 'real' likeness, and more about Cameron's artistic statement, and the artistic conventions used when picturing women in photography. Curator: Precisely. By emphasizing visual texture over clinical sharpness, Cameron asserts a creative autonomy, demonstrating how photography might serve purposes that transcend the simply mimetic. Editor: This image reminds us that understanding artwork involves unraveling complex layers of intention, cultural context, and aesthetic decision. Thank you for guiding us through it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.