Copyright: Public domain

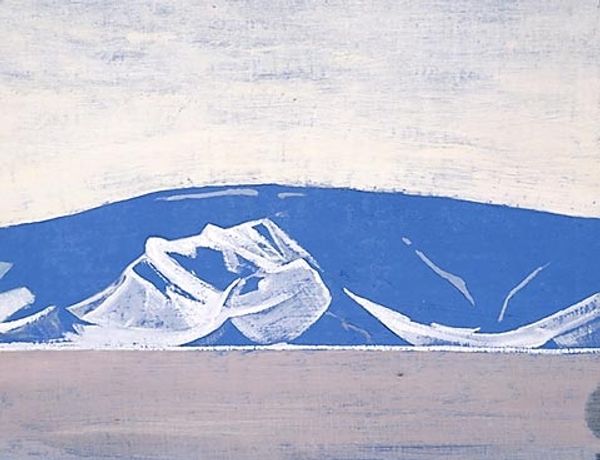

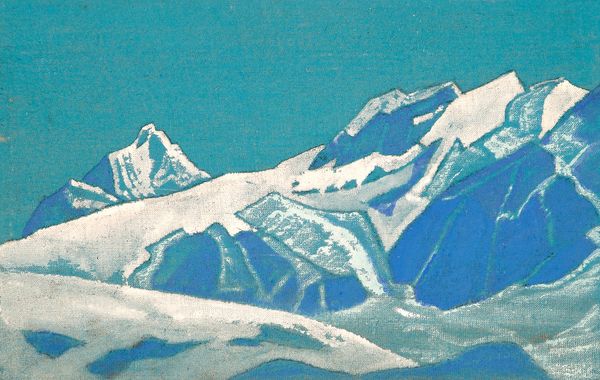

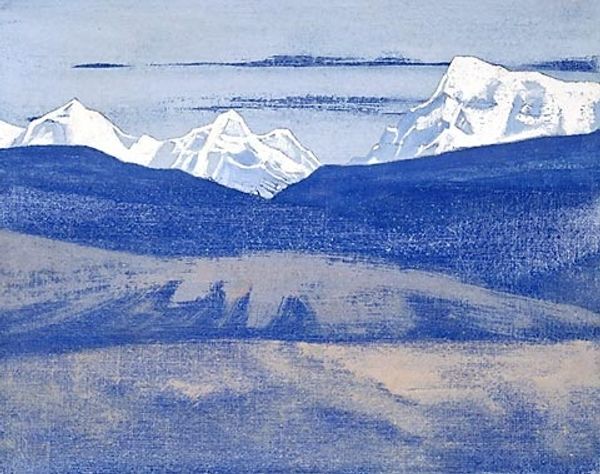

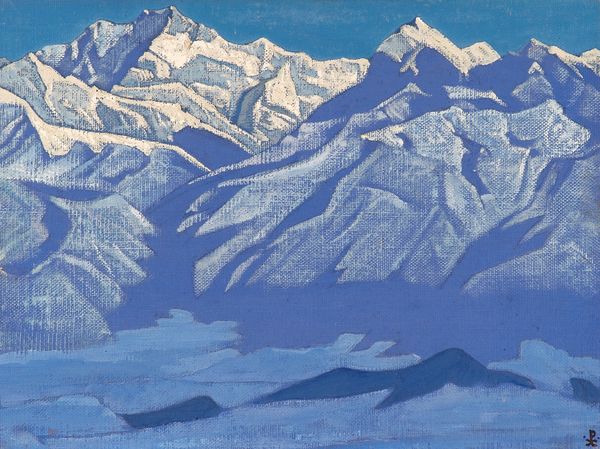

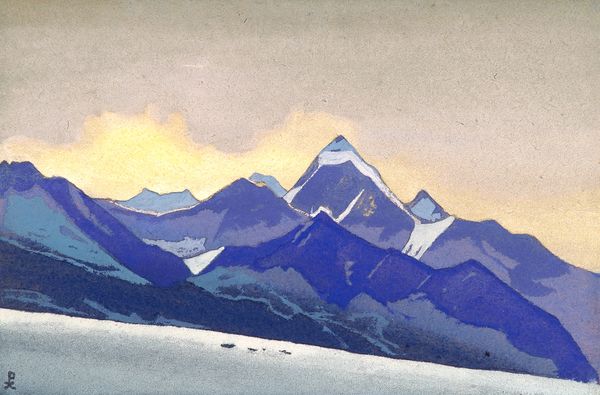

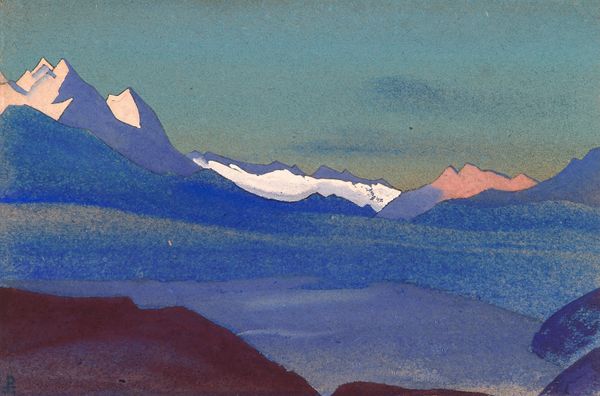

Curator: Ah, Roerich's "Tibet," painted in 1929. Notice the gouache and tempera, very typical of his approach. Editor: It’s striking! The colors are so bold and geometric; almost dreamlike. I'm drawn to the use of tempera and gouache on... what *is* the support here? What’s your perspective on this piece? Curator: We must consider the material conditions. Roerich wasn’t simply depicting a landscape. What matters is how his chosen materials -- easily portable and relatively inexpensive like gouache, allowing for swift application -- facilitated his extensive travels across Central Asia. This connects directly to the dissemination of the image and, by extension, Roerich's artistic and philosophical ideas, doesn't it? Editor: So the very act of creating art on the move influenced the style and the message? Curator: Precisely. Look closely at the flat, almost theatrical backdrop. He layers gouache, almost like stage flats, doesn't he? These weren't mere landscapes for Roerich; they were stages for projecting spiritual and political ideals. How does the relative availability of pigments factor in, given the remoteness of the subject? Editor: That's fascinating. It's not just about *what* he painted, but *how* the materials and process became intrinsically linked to his travels, philosophical vision, and, essentially, to reaching a wider audience. I never considered how deeply connected the materials were to his social and spiritual pursuits. Curator: It reveals how art production is entwined with labor, materiality, and ultimately, cultural consumption. Thinking about art this way, always keeps our analysis grounded. Editor: I agree. I'll never look at a landscape painting the same way again. Thanks! Curator: My pleasure. Examining the material production can reshape the very way we interpret art history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.