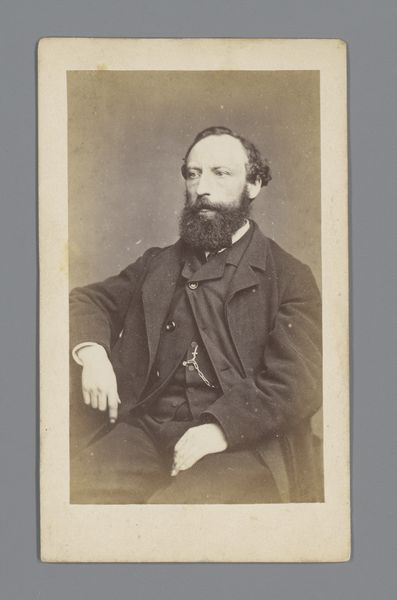

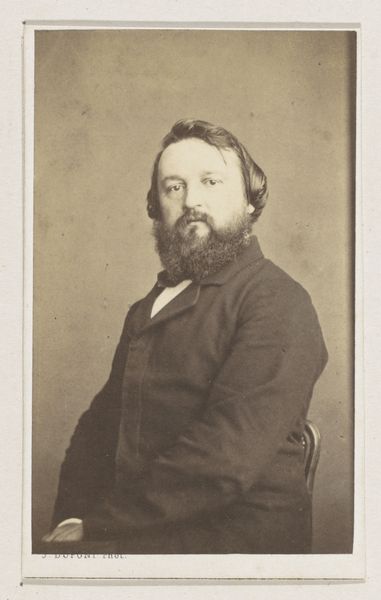

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 62 mm

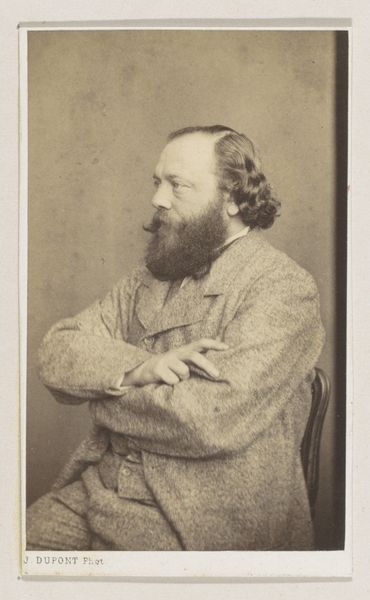

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a gelatin-silver print, a portrait of the painter Henri Adolphe Schaep by Joseph Dupont, dating from 1861. I’m struck by the contrast – the starkness of the sitter's gaze against the soft sepia tones. What strikes you about this image? Curator: What grabs me here is the materiality of the gelatin-silver print itself. This photographic process, relatively new at the time, democratized portraiture, shifting its production away from the traditional artist's studio and the elite. Consider the labor involved in the preparation of the gelatin emulsion, the photographer's skill in controlling light and exposure, the chemistry itself! These elements dictated the final product. How do you think that affected the perceived value of a portrait? Editor: That's a really interesting way of thinking about it. I suppose it made portraits more accessible but maybe less ‘precious’ if they became easier to produce? Did this early form of reproducible portraiture influence painting? Curator: Absolutely! Photography provided painters with a new means of studying their subjects and arguably impacted the status of painting itself. Dupont’s ‘J. Dupont Phot.’ signature in the corner feels like both a statement of authorship, and an early attempt to compete within the market, branding the reproducible. What can we learn from Schaep’s profession and the decision to produce a photograph? Editor: Perhaps Schaep himself saw value in aligning with this new technology to market himself? I’m not sure I had considered the commercial aspect of art and photography so directly. Curator: Precisely! By viewing the photograph as a commodity, made through the skilled labour of its technicians and marketed through recognizable branding, we are viewing its context of creation in a fresh light. Editor: This deeper dive has changed my view entirely. The conversation around labor and branding is fascinating! Curator: Indeed! Examining the material processes, the labour, and the social context truly reveals so much about a seemingly straightforward portrait.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.