drawing, print, etching, watercolor

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

water colours

# print

#

etching

#

perspective

#

watercolor

#

coloured pencil

#

cityscape

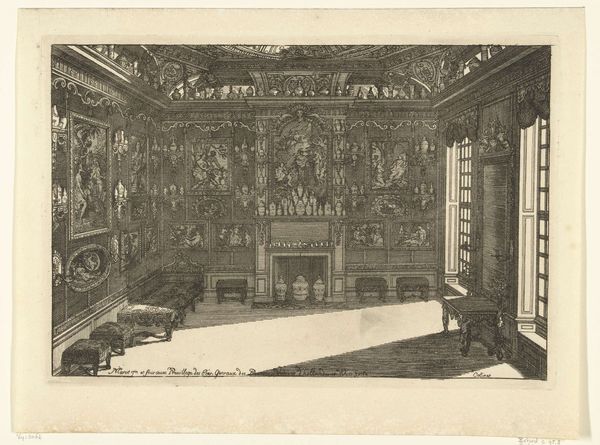

Dimensions: height 193 mm, width 240 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

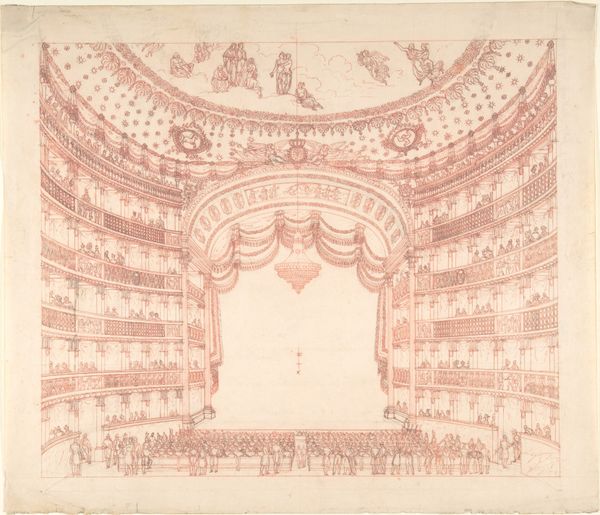

Curator: Here we have "Interior of the Teatro alla Scala in Milan," created sometime between 1800 and 1835 by Carlo Gilio Rimoldi. It’s a print combining etching and watercolor. Editor: It strikes me as a marvel of perspective. The way the artist uses color and light—or rather, a selective absence of it—draws the eye deep into the stage, emphasizing the immense scale of the opera house. Curator: Absolutely. Consider that the Teatro alla Scala was more than just an opera house; it was a pivotal space for political and social gatherings. Rimoldi’s work captures the heart of Milanese society in the throes of Neoclassical fervor. The theater itself embodies Enlightenment ideals of order and reason, providing a backdrop where class distinctions were both performed and challenged. Editor: Precisely! Note how the tiered boxes literally stack the social hierarchy, but all eyes ultimately converge on the stage, unifying them in shared spectacle. The etching provides a rigorous, architectural framework, almost a cage for human passions, with watercolor adding subtle gradations and highlighting the theater’s opulent materiality. Curator: That shared spectacle often masked underlying tensions. The opera became a forum for nationalistic sentiments during the Napoleonic era. The very act of attending was often fraught with meaning, signaling one’s political allegiance and social aspirations. These boxes—which the formal elegance and sharp perspective invite our gaze—were in fact closely guarded territories in their own right. Editor: Indeed. Also consider the central vanishing point, carefully positioned in the center stage. It’s not just a technical accomplishment, it invites our gaze, forcing us to interpret that very moment represented on stage as a key to interpreting society itself. Curator: It brings us back to the role of the opera house during periods of upheaval, serving not just as entertainment, but a barometer reflecting—and often, refracting—Milanese social currents. I now have a whole new interest in the ways people of color were excluded from the grand spectacle that played out in this architectural wonder. Editor: Looking at Rimoldi’s print now, I understand that beauty isn’t merely aesthetic but a system through which historical, sociopolitical relationships become both framed and visible.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.