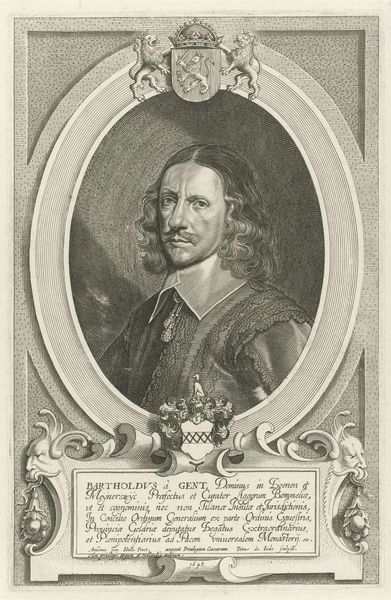

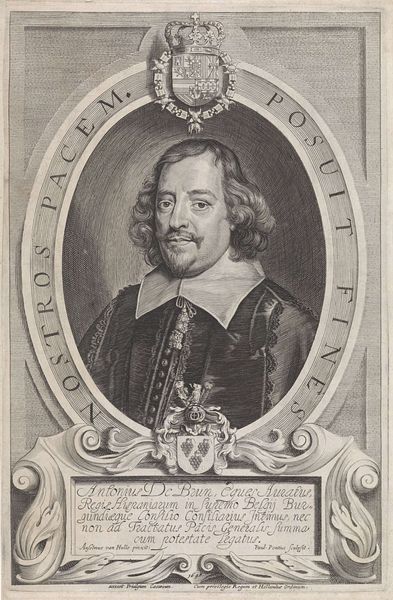

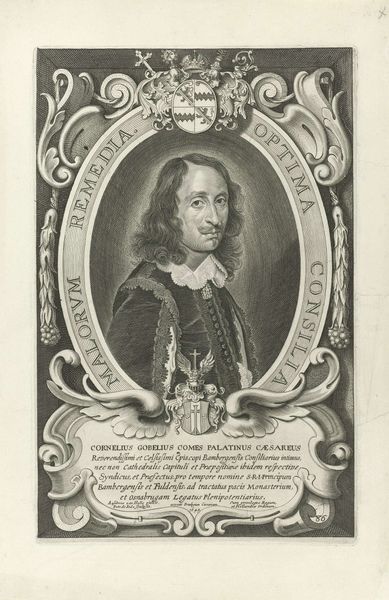

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 306 mm, width 199 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is a 1648 engraving by Paulus Pontius, currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It's a portrait of the diplomat Philippe Le Roy. Editor: My first impression is that it’s incredibly detailed! There’s an almost oppressive weight to the frame around his face. Curator: Note the intricate oval frame; it bears the inscription "Regnare est servire Deo" – "To reign is to serve God." Structurally, it reinforces a visual hierarchy, centering Le Roy as the subject but also subjecting him to divine will. Editor: The heraldry at the top corners speaks volumes, doesn't it? Those coats of arms and the cherubic figure directly above Le Roy project a complex network of allegiances—family, state, and spiritual authority, all converging. The cherub introduces an interesting duality—mortal governance and heavenly mandate. Curator: Precisely! Consider the sharp, linear quality of the engraving. It uses stark contrast to create volume and depth. Pontius masterfully uses the medium to convey texture, from the fine hairs of Le Roy’s moustache to the heavy folds of his robe. Editor: And what about Le Roy’s chain and the figures flanking the crest at the bottom? They feel less about personal adornment and more about broadcasting affiliation and societal role. The entire piece almost serves as a symbolic resume—his accomplishments rendered visually. Curator: His gaze is critical to the overall composition. Le Roy is looking directly at the viewer. It suggests an intentional presentation of himself—carefully constructed and undoubtedly controlled. The clarity of line and precise hatching underscore this deliberate attempt to create a lasting image of power. Editor: Thinking about it all, this portrait acts as more than just a likeness. It's a study in the symbols of power and obligation. Curator: A sophisticated blend of Baroque aesthetics and political iconography—Pontius gives us much to consider through his keen manipulations of form. Editor: Indeed. It has changed my view of 17th-century portraiture.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.