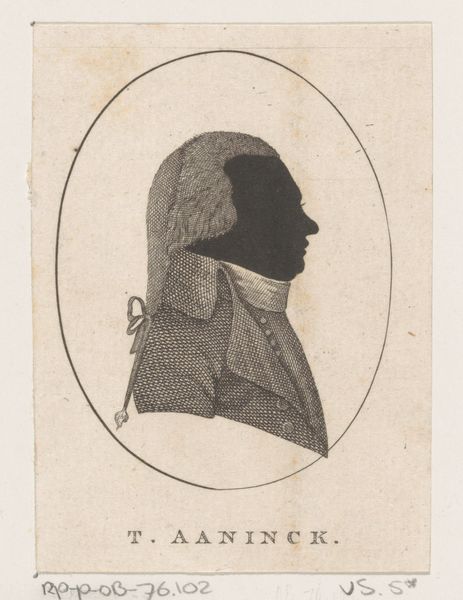

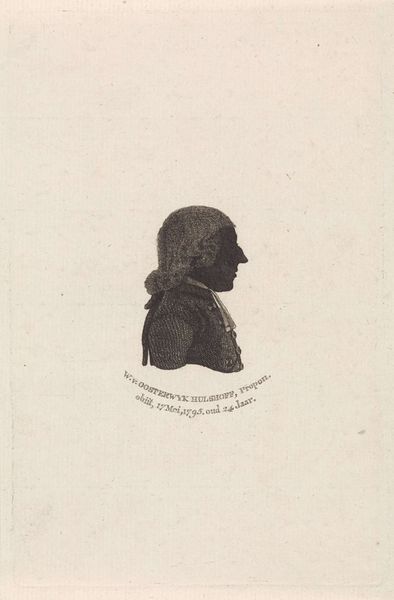

Silhouetportret van de predikant Heere Everts Oosterbaan 1782 - 1851

0:00

0:00

danieliveelwaard

Rijksmuseum

drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

amateur sketch

#

light pencil work

#

shading to add clarity

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

idea generation sketch

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

sketchbook drawing

#

pencil work

Dimensions: height 188 mm, width 128 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a "Silhouette Portrait of Reverend Heere Everts Oosterbaan," attributed to Daniël Veelwaard, from between 1782 and 1851. It's a pencil drawing. It has a sort of stark, formal feel to it, yet the sketchy quality makes it feel quite accessible. What stands out to you? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the materials themselves. Consider the social and economic implications of pencil drawings as a means of portraiture in this period. Unlike painted portraits, which were often commissioned by the elite, pencil sketches provided a more accessible mode of representation for a broader segment of society. Editor: So, the pencil itself democratized portraiture? Curator: In a sense, yes. Think about the availability of paper and pencils versus the pigments and training required for painting. The sitter, a Reverend, signals to the clerical middle class and his attire speaks volumes about profession and societal status. Can we really understand the nuances of class here by comparing high and low means of production? How does this method speak to its period differently? Editor: I guess I hadn’t considered the economic implications of even simple materials like pencil and paper. Curator: Exactly. We see a negotiation between elite visual language – portraiture - and accessible materiality through pencil, labour and the paper itself! Look at the very texture of the paper, its probable origin, perhaps from a local mill. It’s not merely a picture; it’s a record of social conditions, captured through material choices and their availability. The making becomes the art! Editor: It gives a lot of food for thought on how we usually perceive portraits and how simple this could be achieved. Curator: Precisely, this shift forces us to ask critical questions about art's relationship to labor, production, and who has access to representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.