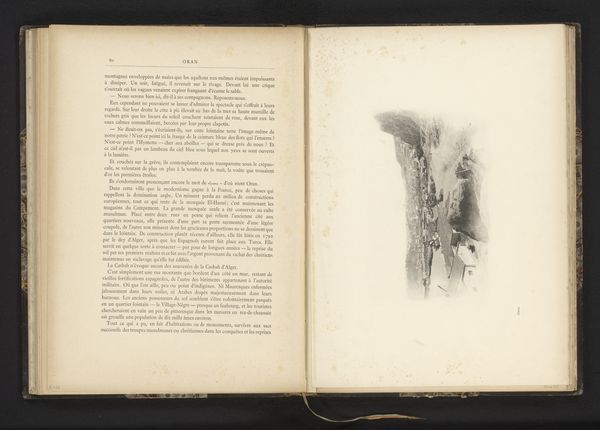

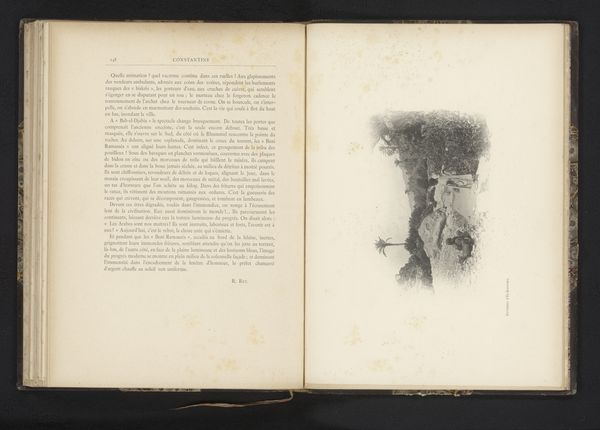

Gezicht op de kloof bij El Kantara te Algerije before 1892

0:00

0:00

julesgervaiscourtellemont

Rijksmuseum

print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 280 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

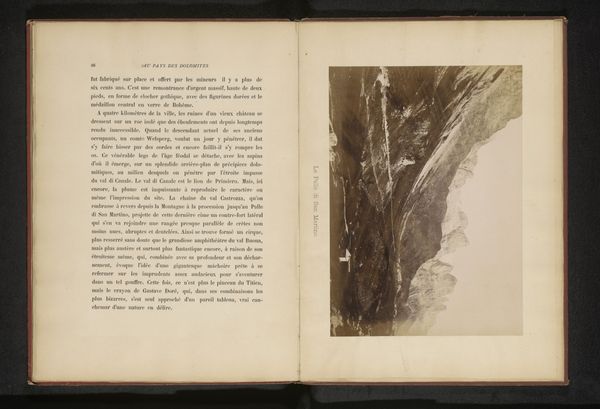

Curator: This photogravure print captures a rather serene view, doesn't it? There’s a stillness that emanates even from the implied movement of the figures crossing in the background. Editor: Indeed. The stark contrasts almost render it dreamlike, yet there’s something about it that feels…colonial, expected? It feels staged, viewed through a very specific, romanticized lens. I wonder how that impacts its reading. Curator: That's an interesting reaction. This image, "Gezicht op de kloof bij El Kantara te Algerije", or "View of the Gorge at El Kantara in Algeria", is attributed to Jules Gervais-Courtellemont and was made prior to 1892. You've picked up on the Orientalist style very perceptively. Notice the emphasis on light, and the way the figures are positioned almost as adornments to the landscape? It's crucial to examine photography not just for its supposed objective capture, but also as a product of its socio-historical context. Who made the image and for what reasons? This was for an illustrated photography book, so a mass-produced art object of the period. Editor: Precisely. And looking at the materials and methods only confirms this interpretation further, doesn't it? Photogravure—a method allowing for mass reproduction but also implying some level of artistic, authorial, control. To me, this image serves as a stark reminder that photography is rarely neutral. What kind of message does this photograph contribute to colonial narratives about North Africa at the time? How were prints like these consumed and circulated? It is now a part of the Rijksmuseum collection. Curator: Good point. And if we start to deconstruct the notion of photography and processes, we realize the labour required here—extraction of raw materials for the print and book, transport across imperial geographies—which are frequently invisible to our readings today. This also reinforces a power dynamic where labor is obscured and made invisible, serving a purpose. Editor: So true, that labor continues to echo today within debates around repatriation, extraction, cultural ownership, and legacies of power...I'm so intrigued by the questions this piece poses in such a gentle form! Curator: Yes, and hopefully such questioning is something all our listeners also carry forward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.