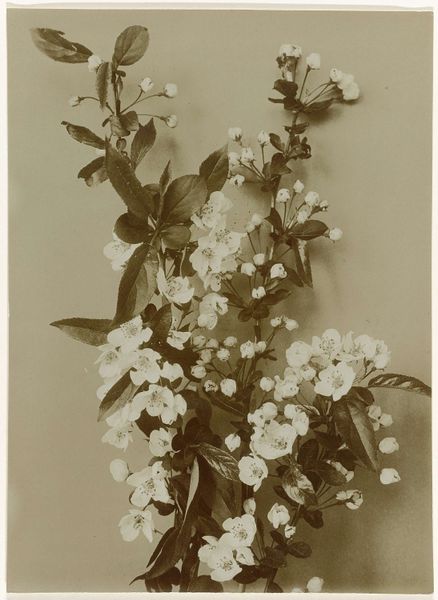

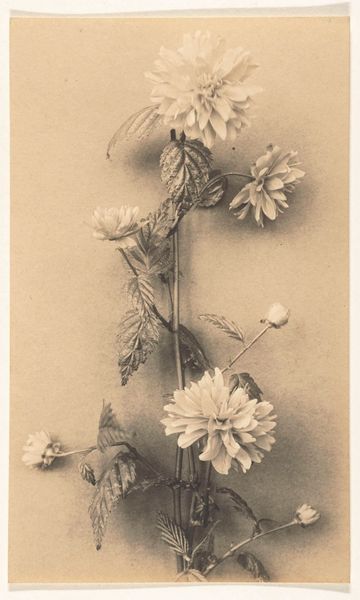

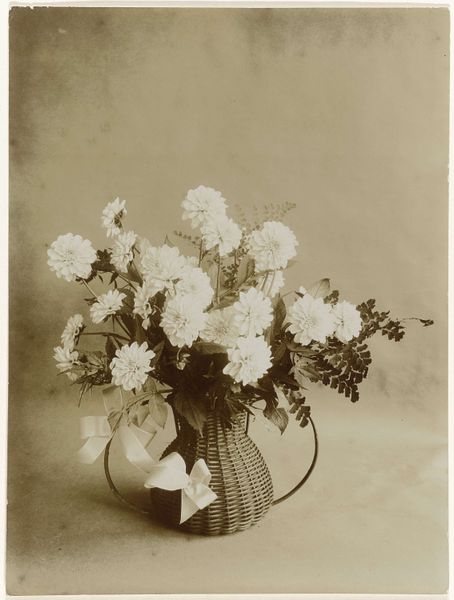

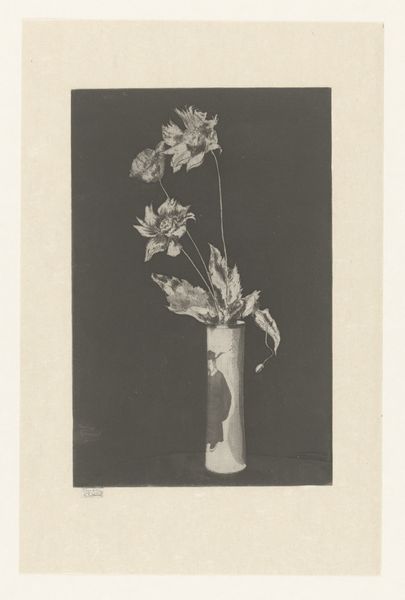

Dimensions: height 202 mm, width 168 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Richard Tepe's "Bloeiende dahlia tegen egale achtergrond", a photograph, probably gelatin silver print, created sometime between 1900 and 1940. It's currently at the Rijksmuseum. There's a dreamy, almost ethereal quality to this image. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Well, let's start with the means of its production. Photography democratized art, didn't it? Consider the availability of materials then. Silver gelatin prints made image creation accessible beyond painting. Who could now afford the tools and chemistry? This shifted the artist's role, focusing on the manipulation of light and the chemistry involved in producing the photographic print, rather than mastery of paint. Editor: That’s a good point! So, the shift in available tools altered the social landscape of art production? Curator: Precisely! Think about who would be engaging in flower photography like this at that time. Was it seen as work for hobbyists, scientists documenting specimens, or as high art? The scale is intimate and personal. Does it reflect mass-produced images or a handmade print, demonstrating the labor of producing it? Editor: It does have a sense of care. But the composition… is there anything that tells us about this particular photographer’s choices regarding composition? Curator: Consider the printing process. This specific gelatin silver print points towards reproducibility. But did the photographer alter any aspects of the production? Did they spend longer to create this work and manipulate it further during printing to give the ethereal feel? Understanding the relationship between production capabilities and consumption helps us really engage with this flower in a historical context. Editor: I hadn’t thought about photography in terms of labour. Thanks, that gives me a lot to consider when I look at art! Curator: The material always matters.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.