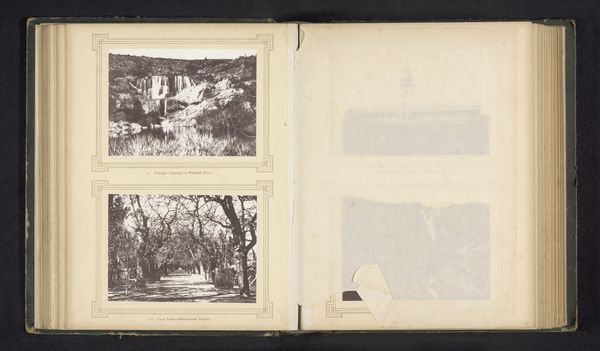

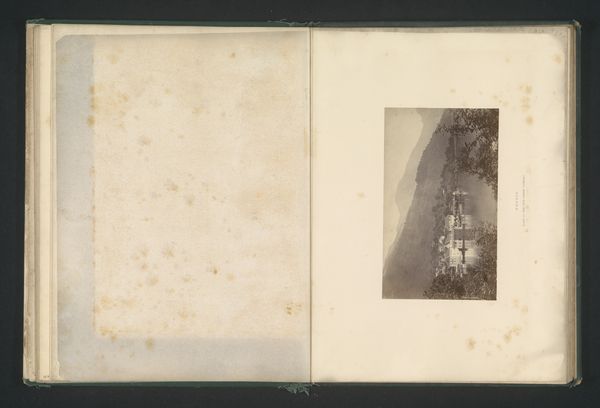

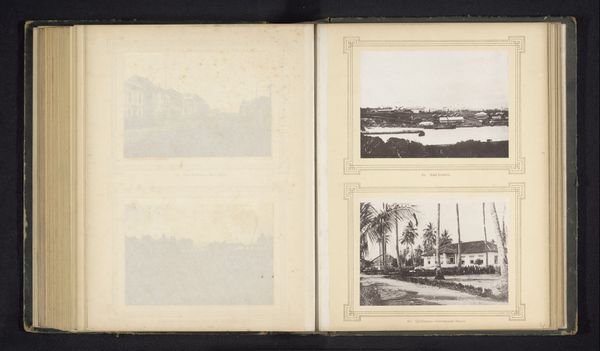

![['Orange Free State, Bloemfontein-Government buildings', 'Tulbagh-Waterfall'] by Sam Alexander](/_next/image?url=https%3A%2F%2Fd2w8kbdekdi1gv.cloudfront.net%2FeyJidWNrZXQiOiAiYXJ0ZXJhLWltYWdlcy1idWNrZXQiLCAia2V5IjogImFydHdvcmtzLzQ5N2VhMWEzLTNkZTctNDQxYi05YzBmLTM2NTUyMDNjMTBmYS80OTdlYTFhMy0zZGU3LTQ0MWItOWMwZi0zNjU1MjAzYzEwZmFfZnVsbC5qcGciLCAiZWRpdHMiOiB7InJlc2l6ZSI6IHsid2lkdGgiOiAxOTIwLCAiaGVpZ2h0IjogMTkyMCwgImZpdCI6ICJpbnNpZGUifX19&w=3840&q=75)

['Orange Free State, Bloemfontein-Government buildings', 'Tulbagh-Waterfall'] before 1880

0:00

0:00

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

appropriation

#

landscape

#

waterfall

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

albumen-print

#

building

Dimensions: height 290 mm, width 219 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Here we have a page from an album containing albumen prints, taken before 1880. The prints feature South African landscapes and architecture. Two prints of note showcase 'Orange Free State, Bloemfontein - Government buildings' and 'Tulbagh - Waterfall'. Editor: My immediate impression is the stark contrast between the architectural and natural subjects. It feels very controlled versus wild. What strikes you? Curator: I’m immediately drawn to the framing, both within the image—the rigid border around each print—and how these scenes might have been deliberately collected together to project particular ideologies of colonial ambition and control. We should unpack the implications of juxtaposing natural beauty with assertions of governance. Editor: That’s a good point. Focusing on 'Orange Free State,' the architectural style is decidedly Western, a visual declaration of dominance in a new land. These buildings project authority, purpose-built institutions… Curator: Exactly. Consider the historical context. This photograph would have circulated during a time when colonial powers were actively shaping the narrative of their presence in South Africa. How does the representation of infrastructure play a role in that? It asserts civilization, control of the landscape and its resources, a sense of permanence. And, interestingly, right beneath that…a pristine waterfall. Editor: The ‘Tulbagh - Waterfall’ is very different tonally and in terms of affect. The scale of the water tumbling down is imposing; there’s a sense of the untamed… Perhaps juxtaposing the built environment with the natural environment was intended to glorify the European ability to not only construct cities but to subdue the natural landscape to their desires? Curator: Perhaps. The choice of perspective certainly has a bearing. Both photographic approaches position the viewer as distant observers, almost detached. Consider how the act of viewing through a Western gaze implicates the spectator as someone outside the natural flow of these locales and communities. The ‘Orange Free State’ structures impose themselves upon the very site line; while the waterfalls and terrain in ‘Tulbagh’ remain remote and impenetrable to any lasting form of settler control. Editor: Absolutely. Seeing them side-by-side really emphasizes the constructed nature of colonial power through image-making, in ways that written narratives might mask. The contrast invites questions about whose perspective is being privileged here. Curator: Indeed. I find myself now seeing them, not as individual scenic views, but pieces of a larger puzzle—pieces that speak to issues of landscape appropriation, cultural imposition, and the complex relationship between power and representation in colonial South Africa. Editor: A compelling reminder that even seemingly innocuous landscapes are politically charged documents, when the lens of power dynamics is focused.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.