#

toned paper

# print

#

personal sketchbook

#

street graffiti

#

coloured pencil

#

coffee painting

#

sketchbook drawing

#

watercolour bleed

#

watercolour illustration

#

sketchbook art

#

watercolor

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

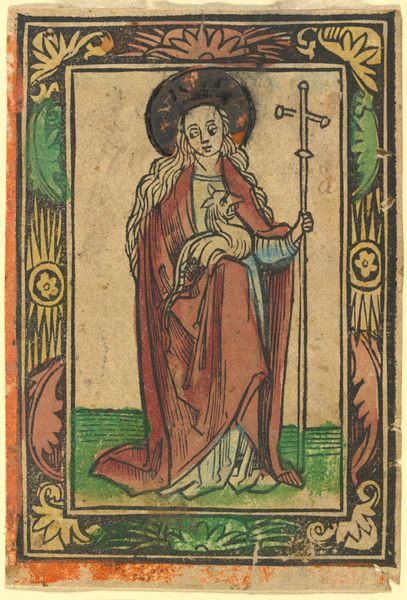

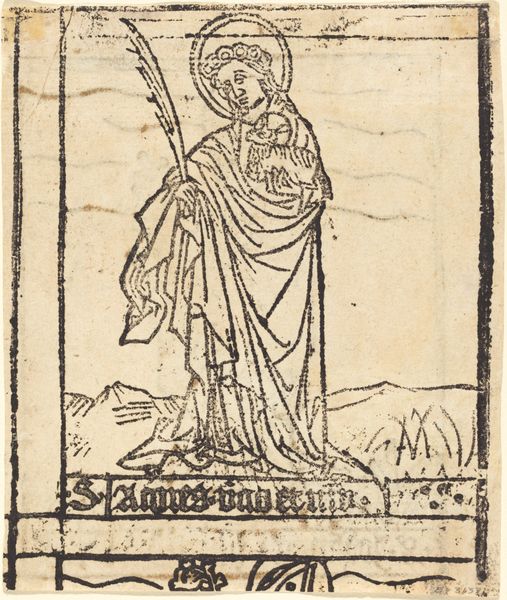

Curator: We're looking at "Saint Catherine of Alexandria," a print made anonymously between 1475 and 1485. Editor: It strikes me immediately as quite austere. The tones are muted, yet there's a boldness to the figure. What do you see in the saint’s symbolism? Curator: Saint Catherine is depicted with her traditional attributes: the sword and the wheel. The sword represents her martyrdom, beheading after refusing to renounce her Christian faith. The wheel refers to the spiked breaking wheel, intended for her execution, which miraculously shattered upon her touch. Editor: And what about the material production of the print? It's done on toned paper and, as it is a print, surely this was intended to be replicated, consumed, not an original painting to be kept in private. I'm curious how accessible such images would have been at the time. Was this sort of print used to spread propaganda or just for simple faith practices? Curator: It’s possible this type of print served multiple functions. Images like this helped disseminate hagiographies – the stories of the saints – providing visual anchors for the faithful. Catherine’s story is a potent narrative of intellect, courage, and divine intervention. The imagery imprints a narrative arc, offering an easily consumed memory device. Editor: I notice too the use of coloured pencil and watercolour here; this adds to the artisanal, more humble quality to it. What social layer did this serve, that may have separated it from richer devotional pieces commissioned at the time by the Church? Was there competition perhaps for whose message would reign? Curator: The print’s materiality would likely place it within a more accessible sphere. While grander works proclaimed faith's glory to the wealthy, these smaller prints perhaps played a crucial role in everyday devotion and served a wide audience within their own spaces. Editor: It’s fascinating how the physical object, made of common materials, links directly to issues of access, power and visibility. That such an unadorned rendering continues to connect us to deeply-rooted narratives and historical contexts seems remarkable. Curator: Indeed. Even now, centuries later, those symbols – the wheel, the sword – instantly conjure a vivid history. It highlights the enduring power of iconography.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.