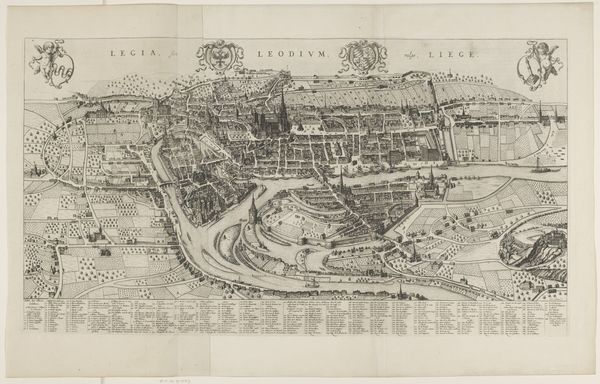

drawing, print, paper, ink, engraving

#

drawing

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

paper

#

ink

#

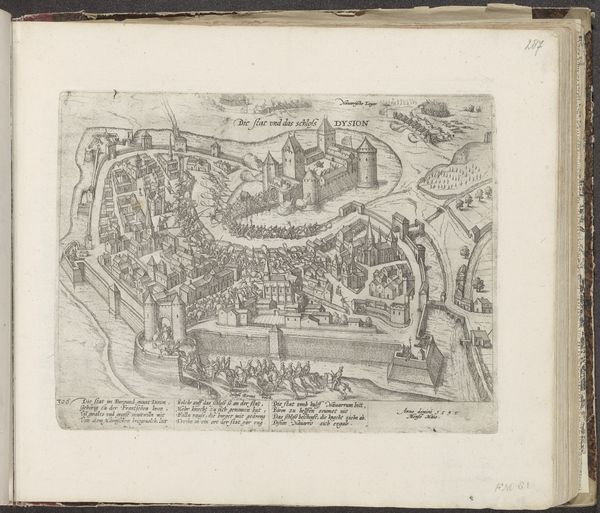

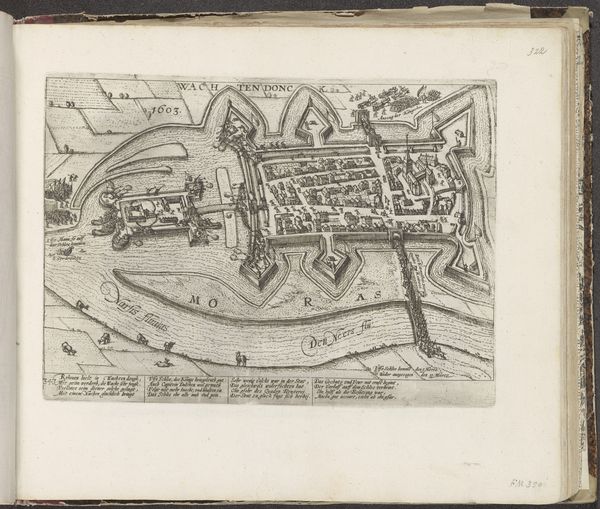

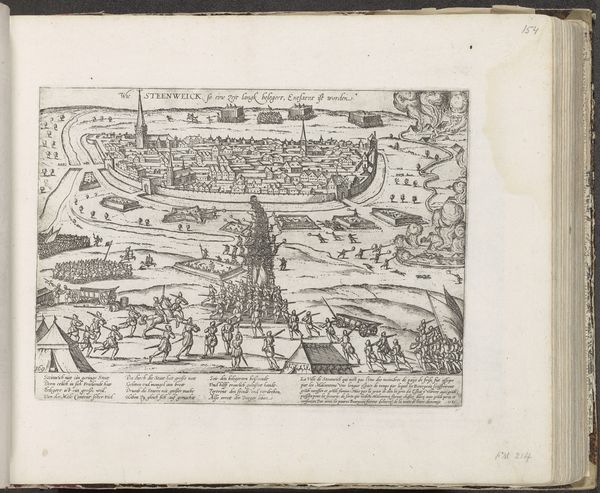

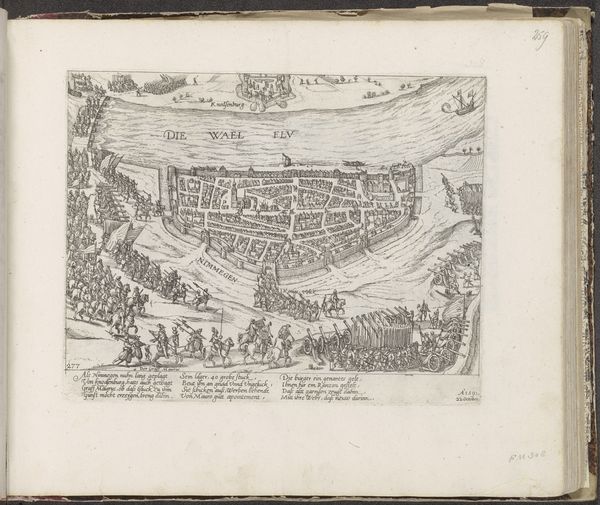

cityscape

#

engraving

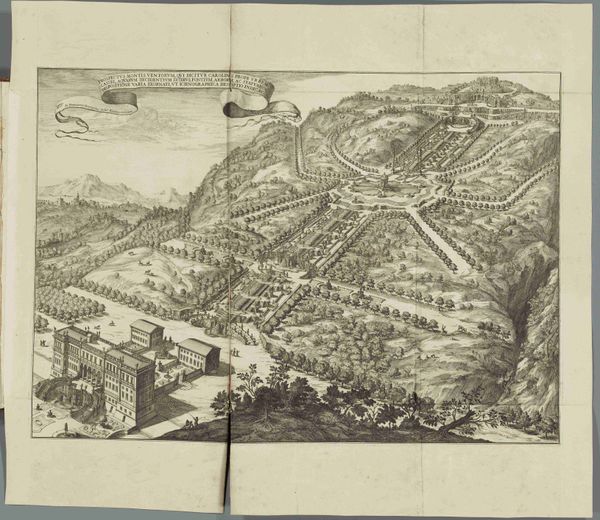

Dimensions: height 438 mm, width 950 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately, I’m struck by the starkness, the near monochrome feel of it. It’s quite diagrammatic; everything appears meticulously delineated yet… static. Editor: Yes, that controlled precision is quite telling. What we’re looking at is "Gezicht op Luik, bestaande uit twee delen," or "View of Liege, in two parts," an engraving crafted in 1652 by Julius Milheuser. Its cool restraint speaks volumes when you consider the turbulent backdrop of 17th-century Europe. Curator: Indeed. We must consider this piece in the context of the Dutch Golden Age, a period of immense upheaval and shifting geopolitical power. Look at how methodically the city is mapped. This reflects the intense drive to survey, to own and to control not only land but also knowledge, something absolutely vital in establishing dominance in a new economic system. Editor: Notice how the network of ink-drawn lines structures the cityscape. This reveals an intent to find balance amid competing perspectives. The formal symmetry suggests this pursuit. It brings structure out of possible social imbalance. Curator: Balance, yes, but perhaps not harmony. Observe the elevated vantage point and overall structure: The composition suggests an underlying tension, a quiet exercise of authority and even surveillance of Liège by those who would exert political control, expressed via detailed artistic output that objectifies the city. How do you feel the materiality contributes to these effects? Editor: The very act of engraving, cutting into the metal plate, mirrors a kind of forceful incision of intellect onto the material world. That incisiveness creates visual structure and emphasizes each form—a semiotic gesture of definition itself. Curator: Exactly. This approach—of both artist and burgeoning elite class—reflects what could only be described as an effort to redefine spatial politics, visualizing social norms of power for posterity. Editor: Considering those meticulous lines and geometric patterns, I see now the attempt to create permanence out of something far more dynamic. Curator: Right. And it reminds me that art is so often used to validate or justify particular power relations, but its status and interpretation often depend on where one finds themself located in history. Editor: Well, it’s been enlightening to look at this artwork with both its visual elements and contextual framework in mind. Curator: Yes, appreciating both intrinsic form and cultural narratives provides greater understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.