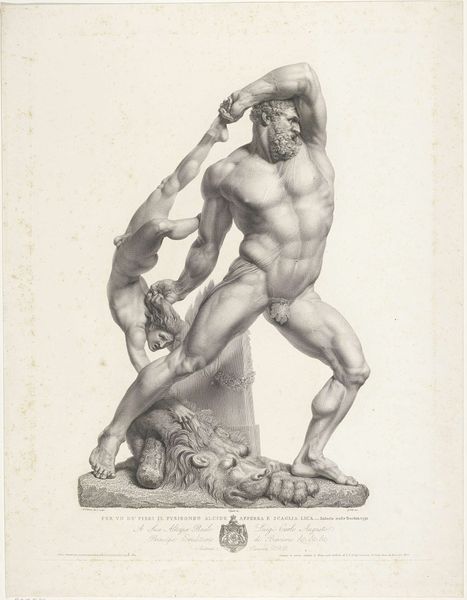

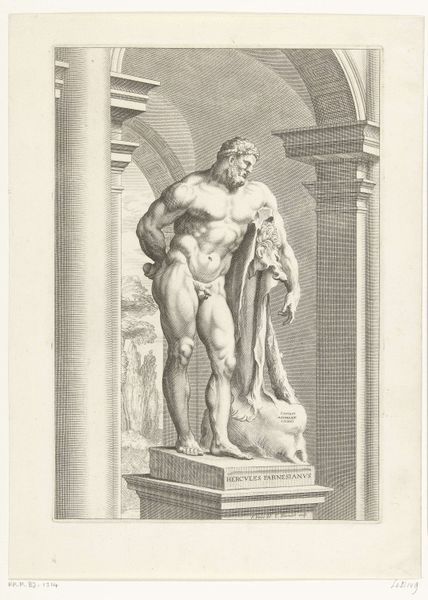

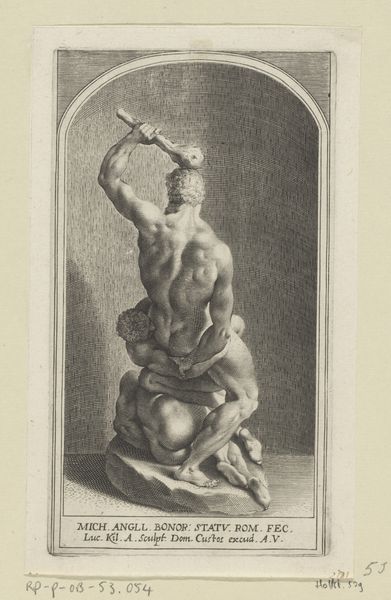

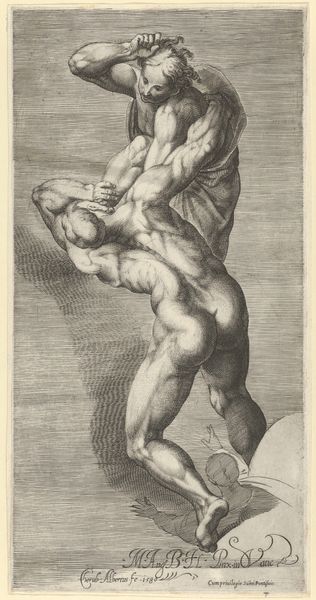

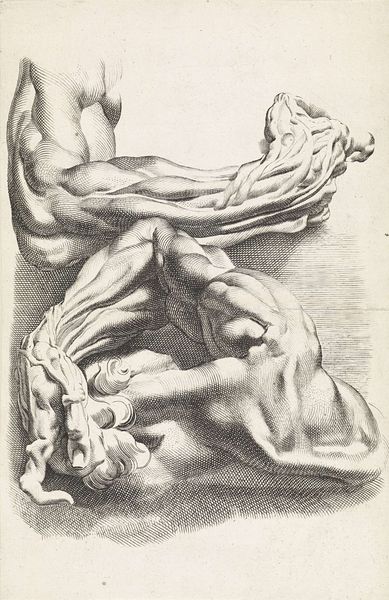

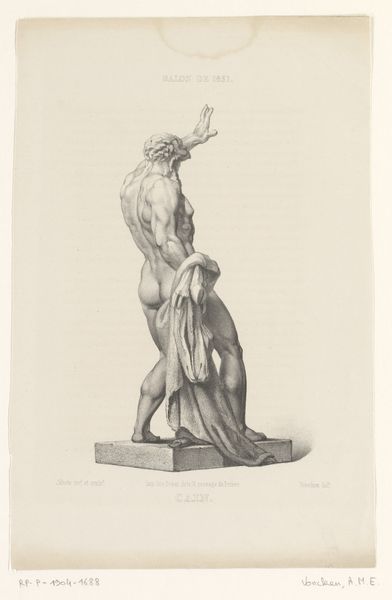

print, engraving

#

pencil drawn

# print

#

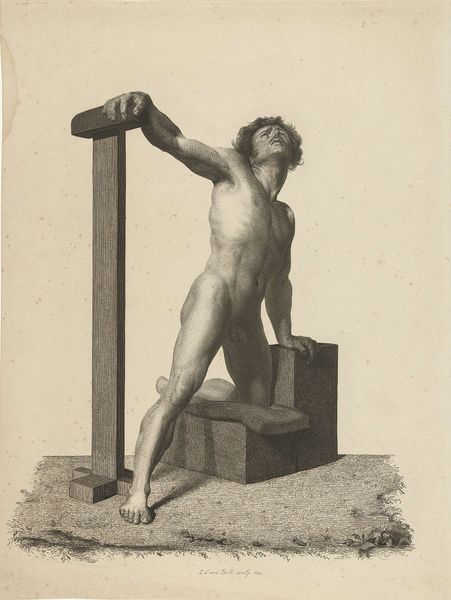

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

classicism

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

graphite

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 620 mm, width 465 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

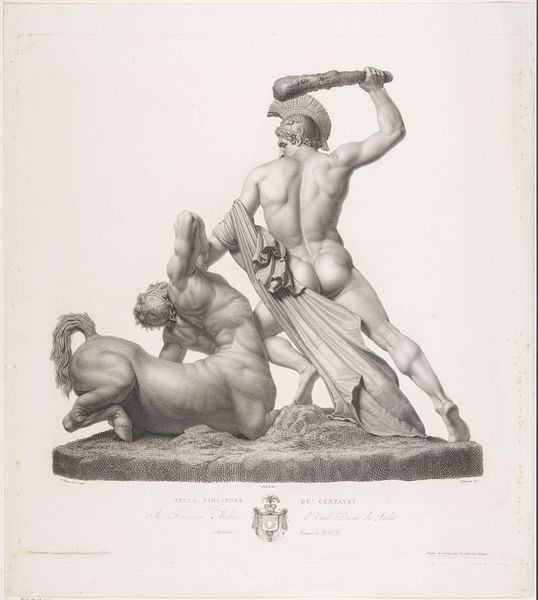

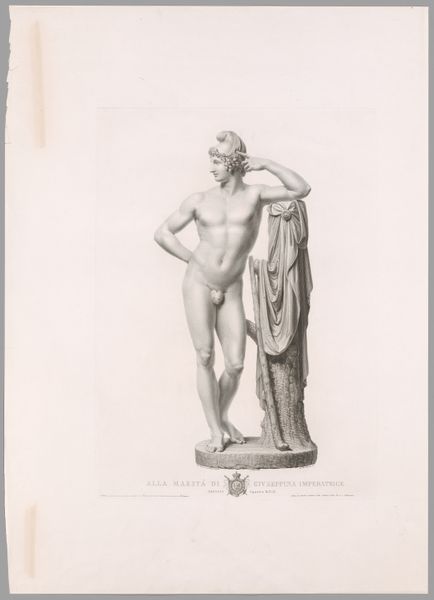

Editor: Here we have Pietro Fontana's engraving, Hercules and Lichas, from 1812, currently housed in the Rijksmuseum. It’s incredibly dramatic – the composition really emphasizes Hercules' raw power as he's hurling Lichas away. What do you see when you look at this print? Curator: For me, it’s about the materiality of the print itself and the means of its production. Consider the labor involved in creating those intricate lines. It's not just about depicting a mythological scene, but also about the social context of printmaking in the 19th century. Who was commissioning these works, and for what purposes? Was it purely aesthetic, or were there didactic or political aims as well? Editor: So, less about the classical story itself and more about who was consuming these images and how they were made? Curator: Precisely. How does the process of engraving – the carving, the inking, the printing – transform the original concept of Hercules's rage? The print democratizes art. Suddenly, these formerly monumental forms become domestic commodities. Are we still grappling with similar questions of art’s accessibility and distribution today through digital mediums? Editor: That’s a really interesting point. I hadn't considered the printmaking process as part of the narrative itself, or how that might transform something initially seen as 'high art'. Curator: Right, Fontana's print blurs those categories. It compels us to reconsider what we traditionally define as ‘high’ art by pointing towards processes and labor involved in artmaking. How would it be seen differently if it was made by an anonymous craftsperson instead of being linked to Fontana? Editor: That perspective gives me a lot to consider about other pieces. Thanks! Curator: And thank you! Considering the material conditions always gives you a fresh reading.

Comments

rijksmuseum over 2 years ago

⋮

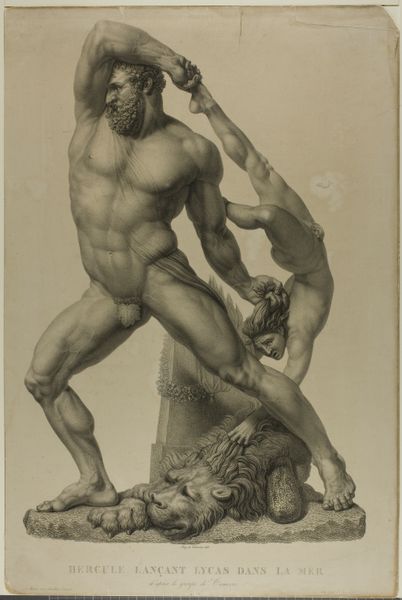

Hercules casts his servant Lichas, who holds on for dear life in vain, into the sea. The vengeful centaur Nessus gave Hercules’ wife his own blood with the promise that it would ensure her husband’s faithfulness. Lichas brought Hercules a garment drenched in Nessus’ blood, however it proved to be poisoned and caused Hercules unbearable pain. The frenzied Hercules killed Lichas. In the end, the desperate Hercules cast himself on a pyre and died.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.