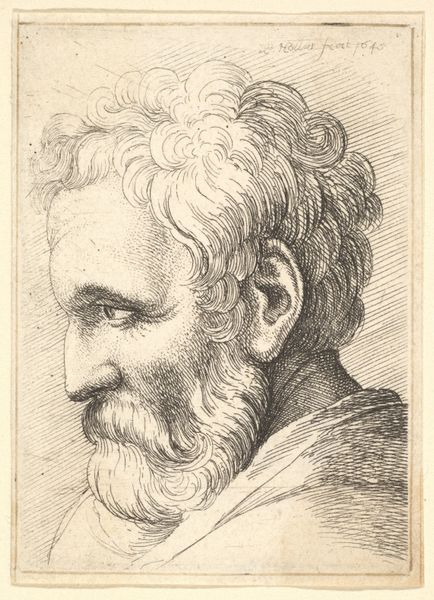

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

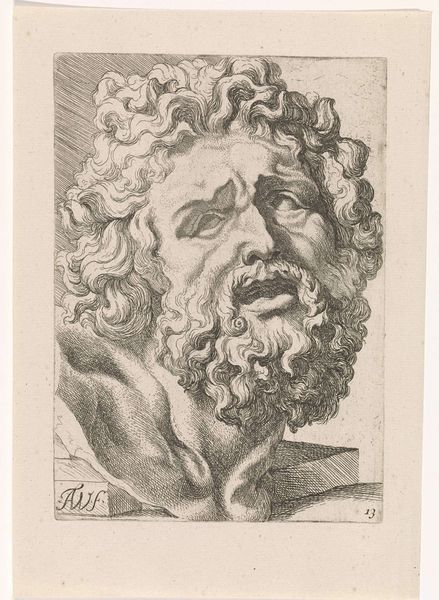

greek-and-roman-art

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

form

#

portrait reference

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

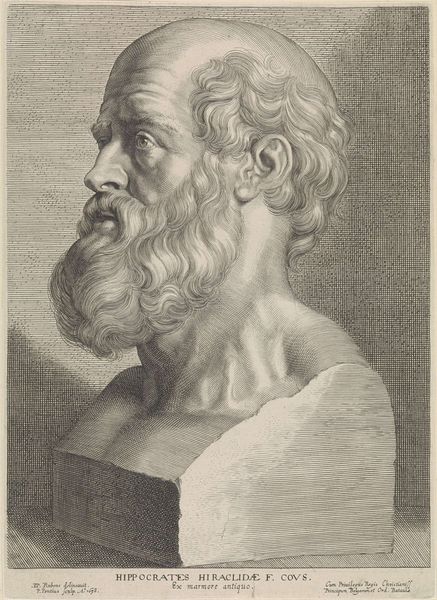

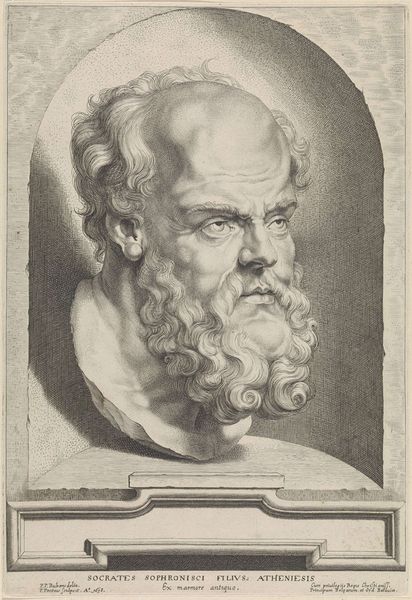

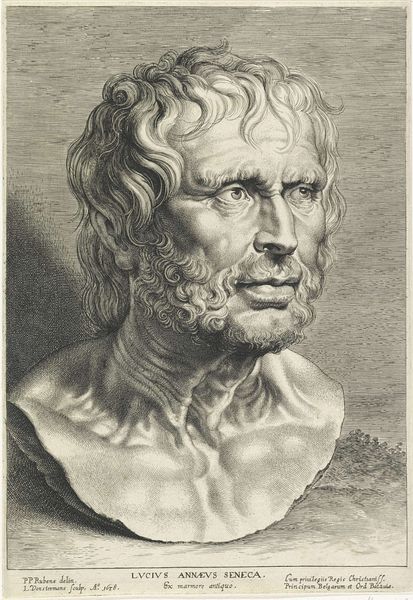

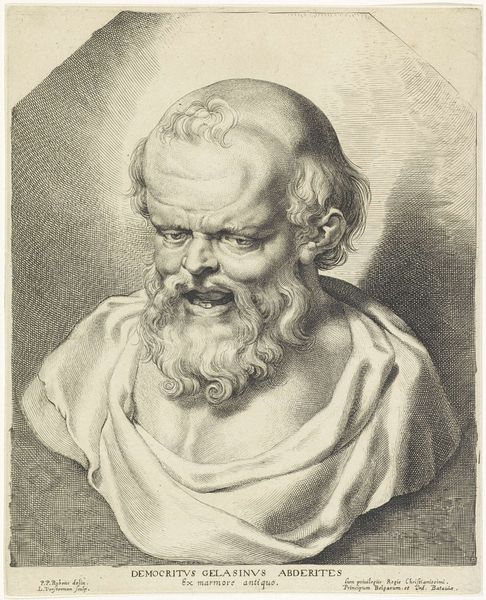

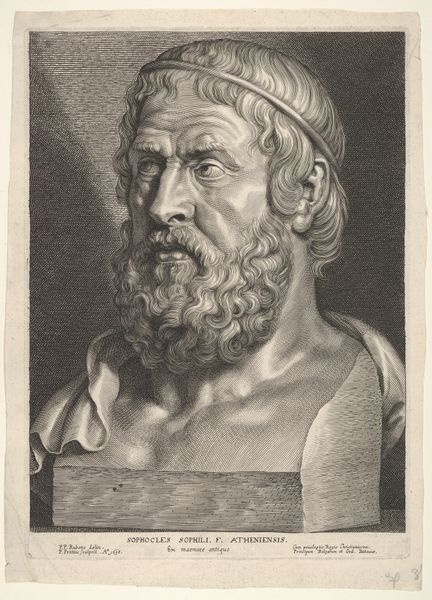

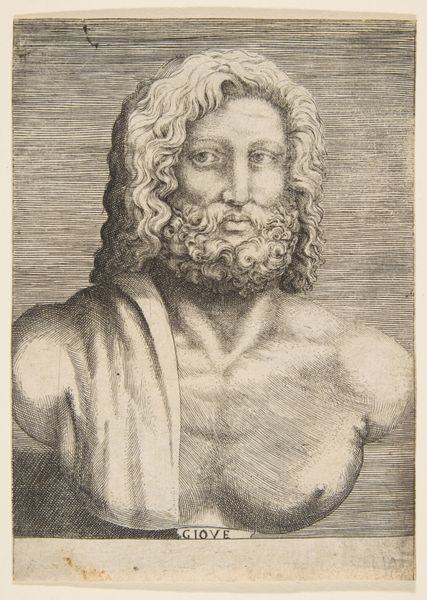

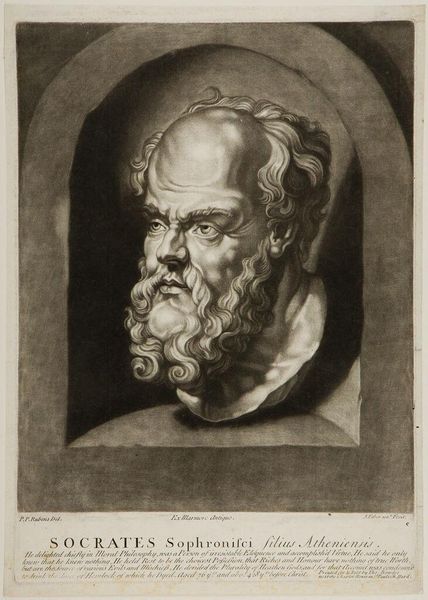

Dimensions: height 291 mm, width 190 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Bust of Plato," made between 1630 and 1638 by Lucas Vorsterman I, what strikes you first? Editor: It’s austere but also… thoughtful. There's a certain gravity conveyed by the artist's precise lines. The subject looks like he carries the weight of ages. Curator: Precisely. Vorsterman rendered this engraving, a print, to create the image after a likely Roman sculpture – note the inscription naming "ex marmore antiquo" – an ancient marble. Considering his practice as a reproductive engraver, the labour is significant. Vorsterman took sketches made by Peter Paul Rubens in Italy and further reproduced it on plates for printing and distribution to a broader audience. Editor: Absolutely. The context is vital. Think about the social and political implications. This print makes classical philosophy more accessible. Plato, previously the domain of elites, is now visually available, to those who might only see it as an aesthetic or social performance of holding intellectual thought. The material shifts meanings here; the original's aristocratic context of antique sculpture contrasts with print's democratization potential. Curator: I agree; the act of transferring from three dimensions of the original to a two-dimensional image on paper is intriguing, isn’t it? And this was after he adapted drawings after a likely three dimensional source! It underscores how essential technical skill and craft were to disseminate knowledge and artistic styles in Vorsterman's time. I wonder who printed and distributed this, too, which would shape reception further. Editor: Right. Questions of access are central. This portrait, though appearing to be an objective representation of an antique bust, has already been through layers of cultural translation and material transformation. I ask myself, too, what narratives of power and authority this kind of classical imagery sought to reproduce. Does the print democratize philosophy, or re-entrench its elitist power under the guise of antiquity? Curator: The quality and fineness with which he replicated this classical form into line print is undeniably high, which added value to his labour. That contrast in texture is interesting— the smooth, imagined marble and the rough lines, isn’t it? Editor: Indeed, by focusing on the visual qualities of a specific material – prints – and tracing how the production process, circulation and reinterpretation shaped this image’s multiple lives allows us to critically address issues of historical agency, reception, and how artistic decisions influence collective cultural consciousness. It really makes me question access to philosophy today. Curator: A worthwhile consideration for how an image functions in time, no doubt! Editor: It certainly gives one plenty to consider in our own image-saturated age.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.