painting, oil-paint

#

portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

romanticism

#

genre-painting

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public domain

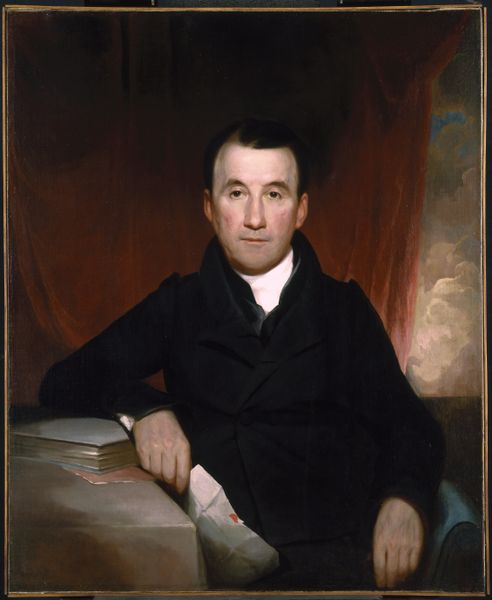

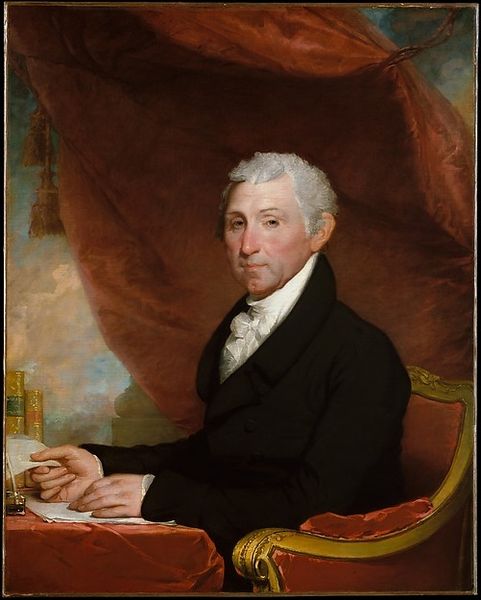

Curator: Let’s turn our attention to this portrait of George Clarke, created in 1829 by Samuel Morse, rendered in oil paint. Editor: My first impression is one of calm formality. The sitter is bathed in a soft light, surrounded by symbols of wealth and knowledge—the books, the drapes. Curator: Indeed. It’s crucial to consider the role of portraits in the 19th century, especially for men of Clarke’s social standing. Portraiture was a visual declaration of status and power. Think about the conventions Morse adheres to: the subject's pose, the carefully chosen backdrop suggesting sophistication. Editor: Right. I also find myself wondering how much Clarke’s identity and self-presentation are constructed versus natural here. His gaze is direct, but not confrontational. It is carefully crafted for the viewers. Curator: Exactly. The backdrop provides a wealth of information on what’s thought to be important by both the sitter and, quite possibly, the artist. Looking through the window, we see his estate. Consider how enslaved people working the land may have been part of that “vista”, even if unacknowledged. This work’s role in normalizing specific class structures must be considered. Editor: And it reflects upon Morse’s worldview, too. He paints this vision of success, consciously or not reinforcing those existing hierarchies. I see art as never existing in a vacuum; it’s always intertwined with complex socio-political systems. Curator: It makes you contemplate the ethics involved when portraying a man of such status. Morse is complicit. I believe art history is often a case study in complicity. We are all implicated in a long history, as curators, as scholars, and in general, as appreciators. Editor: Agreed. Viewing art from this lens changes our expectations. Curator: These subtle yet revealing details allow a discussion that considers not only the history of portraiture but the broader implications of representing wealth and social order at that time. Editor: Yes. Morse’s rendering opens a portal for considering how art played a part in defining privilege and prestige in nineteenth-century America.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.