Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

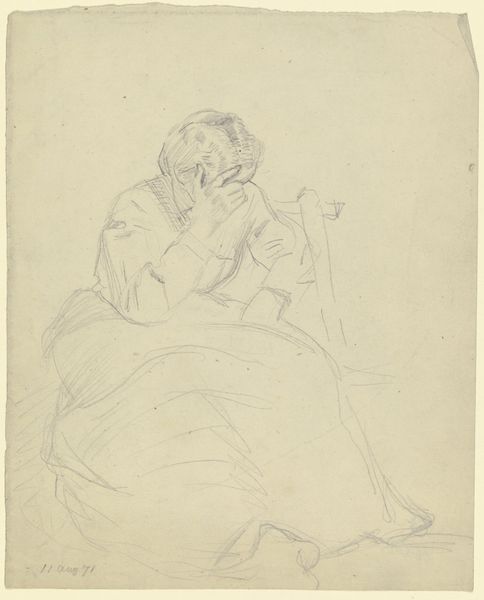

Editor: This pencil sketch, "A Woman Bowed in Grief," from around 1857 by Sir John Everett Millais, evokes such a strong feeling of despair, doesn't it? The woman's posture just screams sadness. What do you see in this piece beyond the obvious emotion? Curator: It's more than just sadness; it’s a posture of ancient lament. Note how her form echoes mourning figures from classical antiquity, yet Millais grounds her in a tangible Victorian reality through the suggestion of dress. Grief transcends time, but its visual expression is culturally coded. Do you see how the sketch’s lightness contrasts with the heaviness of the subject? Editor: Yes, there's a real tension there. The light pencil work almost makes it feel fleeting, like the grief itself is temporary. Does that contrast affect its symbolic meaning? Curator: Precisely! Consider how light is often used as a symbol of hope or divinity. Its delicate presence here suggests that even in deep sorrow, there remains a flicker of something beyond despair. Think of Renaissance paintings of Mary Magdalene; even in grief, the divine is present. Is there an implied narrative to her grief? What has she lost? Editor: Perhaps a loved one? Or maybe something less tangible, like innocence or faith? I guess the sketch leaves it open to interpretation. Curator: Indeed. The universality of grief allows for personal projection, tapping into our shared human experience. The artist provides the form; we provide the emotional content. It becomes a mirror reflecting our own losses and consolations. Editor: That's a powerful idea. I’ll never look at simple sketchwork the same way. Curator: Symbols offer infinite emotional landscapes and the best are capable of holding cultural and psychological depths that are often left untouched by literal depictions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.