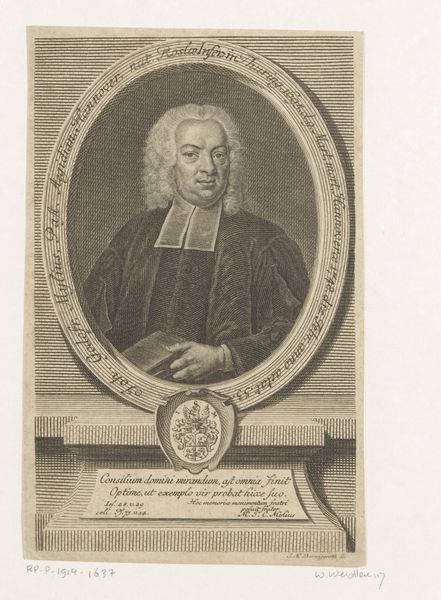

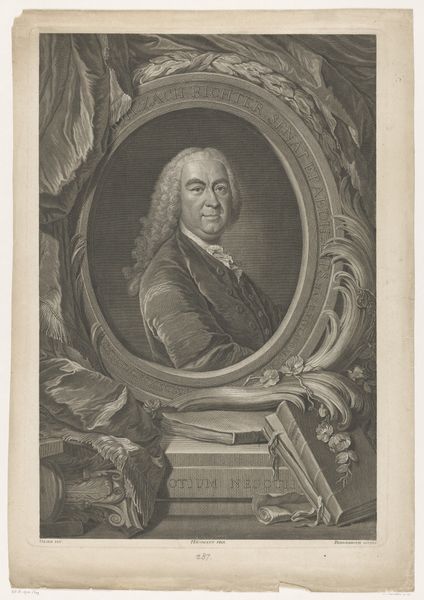

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

archive photography

#

historical photography

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 346 mm, width 216 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is "Portret van Johann Caspar Ulrich," an engraving created in 1751. You can find it here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The intricacy is captivating! The meticulous detail in the rendering of textures, like the fabric and the books, is immediately striking. There is a certain austerity that I see, too, appropriate for the sitter. Curator: Indeed. Considering Ulrich's role as an Abbot and Pastor, such representations were strategic. Note how the print positions him—a man of God, wisdom and letters— within a deeply stratified religious structure. The materials around him – the books, paper and quill – speak directly to literacy and intellectual power in the 18th century. Editor: Absolutely, the weight of those heavy tomes! It emphasizes the labor of learning and the construction of knowledge, which has material and social dimensions. It also prompts consideration of the labour involved in creating the artwork itself. Think of the skilled artisan meticulously working to produce this image in multiple copies, contributing to the circulation of this man's image and, by extension, his authority. Curator: Precisely. And we cannot overlook the performative nature of portraiture in solidifying identity. Ulrich is portrayed at eye-level, framed, almost literally, as an authority in the community. These Baroque era portraits helped construct a particular visual language of power, solidifying hierarchy, race, and gender structures within a broader socio-political context. Editor: I agree. Considering that so much labour and so many valuable materials have gone into rendering the sitter, that labor really tells us a lot about the power of the patron and the role he held in society at the time. The value attributed to portraiture speaks volumes about how certain individuals were seen to embody, on behalf of those who they served, certain virtues of their particular class, race, and gender. Curator: Looking at this artwork today encourages questioning whose stories get told and how representation operates as a tool within asymmetrical power relations. Editor: And to consider the complex, often invisible, processes of labor and material consumption embedded in even a seemingly simple portrait from the past.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.