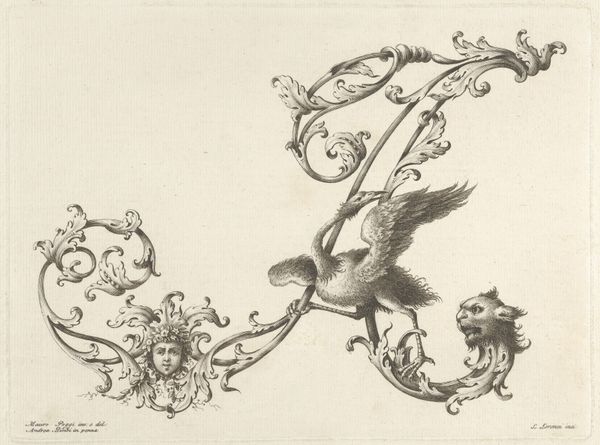

print, engraving

#

baroque

# print

#

pen sketch

#

landscape

#

geometric

#

line

#

islamic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 185 mm, width 238 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Welcome. We’re standing before “Afrika,” an engraving dating from between 1719 and 1749. The printmaker was Philipp Andreas Degmair, and it’s now held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: What a fascinating menagerie! My first impression is this elaborate decorative arrangement teeters between the factual and pure fantasy. The sharp lines create an almost scientific yet playful cataloguing. Curator: Absolutely. Its symbolic weight is deeply embedded in the European imagination of the time. Africa here is constructed from a series of images meant to conjure the “dark continent,” blending observations with myth. Notice the ostriches and what seems to be a carefully placed pyramid—hallmarks of exotic otherness. Editor: Yes, and I'm curious about the choices regarding the materials used in its production. The precision of the engraving, that ability to mass produce… It speaks to the evolving technologies of the printing press during that period and the dissemination of knowledge—or, in this case, perhaps the creation and solidifying of colonial-era myths. Curator: Indeed, printmaking allowed for these visual tropes to spread far and wide. The visual language Degmair employs reflects the power dynamics between Europe and the world it sought to understand and dominate. Even the inclusion of insects lends a specific weight, embodying ideas about tropical diseases. Editor: I agree. And I can't ignore how labor went into producing the print—the craftsman, Degmair himself, spending time etching the design into the plate. This meticulous act transformed the representation into a consumable object for the European audience. Curator: And those details speak volumes. The engraving's symbolic vocabulary isn't just a representation of a place, but of the cultural anxieties and aspirations that underpinned it. The crescent adds another layer—invoking associations with the Ottoman Empire, Islam, and North Africa, underscoring complex perceptions. Editor: So while appearing whimsical and even a bit innocent, it functions more like an ideological blueprint printed on paper. I see the social processes of imagining a world through consumable artwork that makes it less remote and understandable for consumers in Europe. Curator: Precisely. Its visual power resides in its ability to package Africa into a series of accessible—if often skewed—symbols and markers. It makes me reflect on how continuity of images in turn constructs perceptions. Editor: Yes. Thinking through how a printed picture—of all the available mediums—shaped historical narratives is something to keep at the front of my mind after looking at Degmair's work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.