silver, print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

silver

# print

#

landscape

#

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

Dimensions: 16 × 22.7 cm (image/paper); 31.7 × 43.5 cm (mount)

Copyright: Public Domain

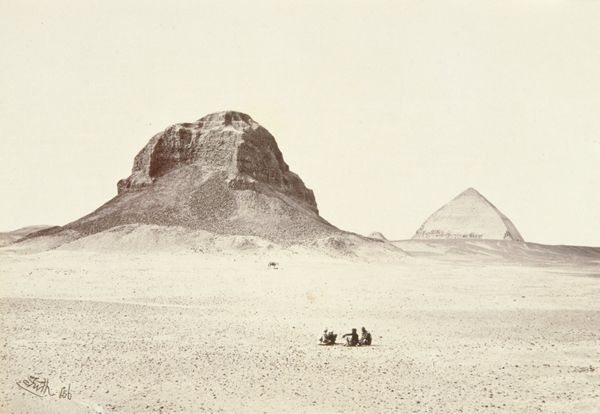

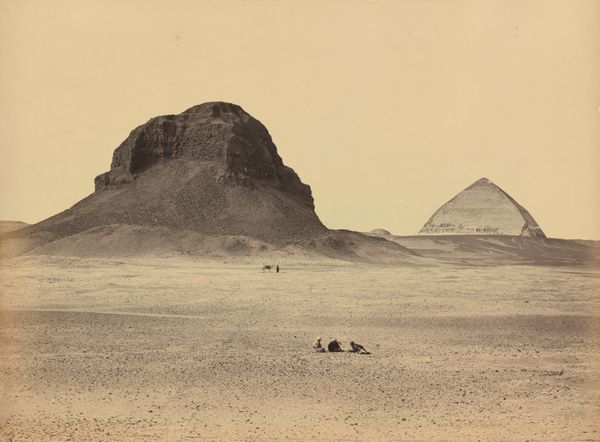

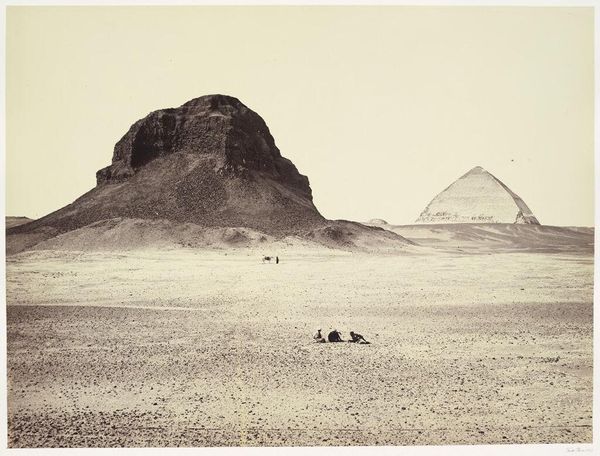

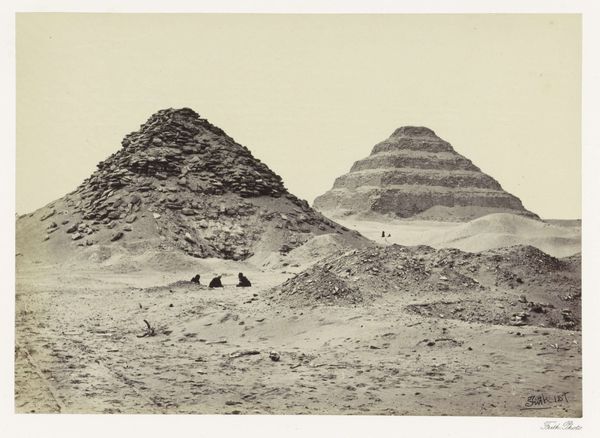

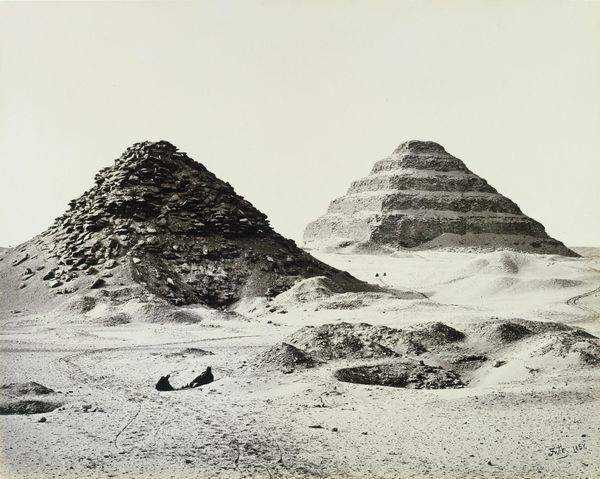

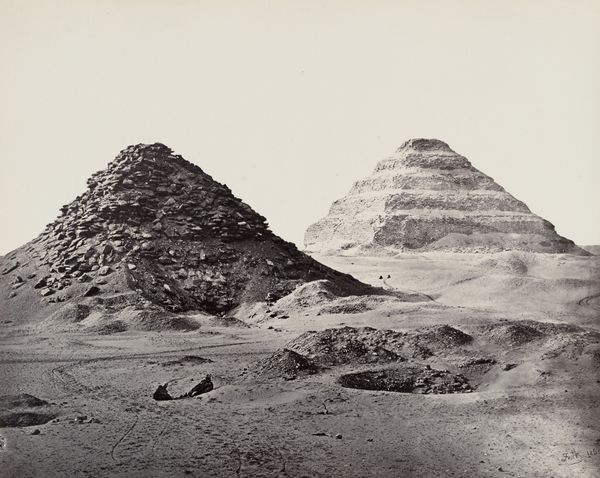

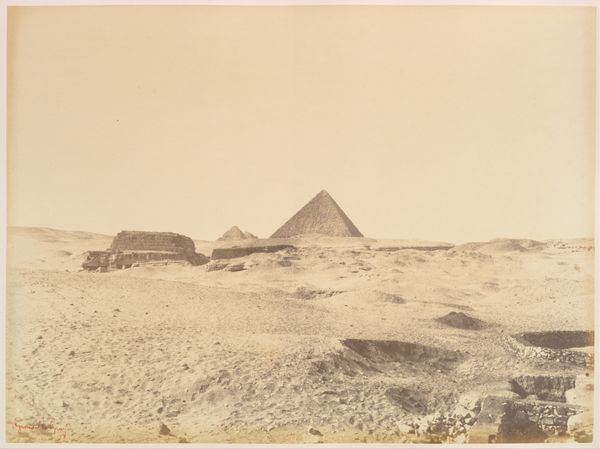

Curator: This is "The Pyramids of Dahshoor," a gelatin-silver print by Francis Frith, dating to 1857, a striking example of early landscape photography from Egypt. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the sheer expanse of that creamy sand, dominating almost the entire composition. The pyramids themselves seem dwarfed, almost secondary. Curator: Indeed. Frith was captivated by Egypt. He understood the power these monuments held, yet he also recognized the broader, often romanticized European interest in the region. Photography, like this piece, served to disseminate that vision widely. It's important to remember the political and cultural context: these images became powerful tools in shaping perceptions of the Middle East. Editor: I see that, but look at how he's structured the picture plane. The darker, more amorphous shape of the Bent Pyramid anchors the left side, balanced by the clearer geometric form of the Red Pyramid on the right, with the figures seated in the foreground as a compositional bridge. He understood how to use the interplay of light and form. The almost monochromatic palette adds to the timelessness, doesn't it? Curator: The tones, in this photographic medium, do lend a sense of timelessness, as you noted. Yet they also subtly reinforce the prevailing views of Egypt, portraying a land steeped in antiquity, removed from contemporary concerns. Think about how access to these sites was often mediated by colonial interests, influencing the way people interpreted and appreciated the image. Editor: It is impossible, even when thinking about visual design and the language of shapes to ignore those power dynamics. But the fact that this is a photograph, not a painting or an etching, also adds something to the picture’s meaning and impact, doesn't it? The purported "objectivity" of the photograph gave it extra weight. Curator: Precisely. That presumed objectivity allowed these images to circulate as documents and artworks reinforcing both scholarly and colonial narratives. Editor: So, on the one hand we can appreciate Frith’s careful balancing of light and shadow and on the other, acknowledge how the image and its circulation served particular socio-political interests. Curator: An artistic rendering shaped by complex historical currents and cultural perceptions. Editor: A synthesis of artistic intent and societal forces frozen in a moment.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.