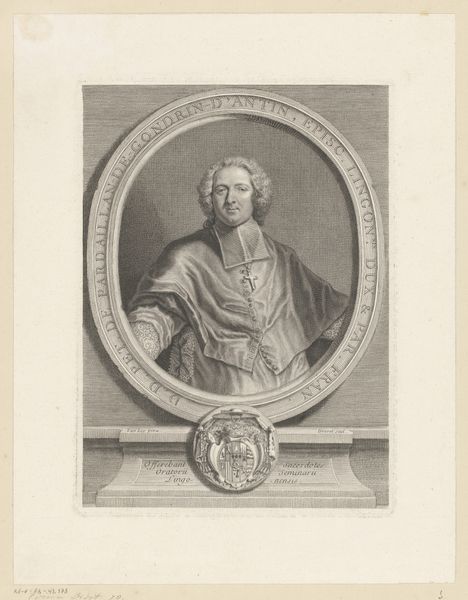

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

personal sketchbook

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 200 mm, width 165 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Portret van Arvid Bernhard Horn," an engraving from 1727. The textures achieved with just lines and dots are amazing, especially on his fur-lined robe! It gives a real sense of luxury. What do you see in this piece that I might be missing? Curator: Beyond the skilled engraving, I'm drawn to how this piece documents 18th-century systems of power and production. An engraving like this was rarely unique: it allowed for reproduction and circulation of the image of important people across great distances, impacting societal status. Note the symbols: the robes of office, his family crest, and even the cane. Each element is carefully reproduced for maximum societal impact. Editor: That’s a fascinating point! I hadn't considered it in terms of mass production, especially before photography. Does the choice of engraving itself signify something about the subject's social standing? Curator: Absolutely. Engraving was a meticulous, labor-intensive process, demonstrating value of both the material itself, and in the artisan commissioned to do it. So it acts not just as a portrait, but a commodity crafted to maintain social power. Does considering the piece in terms of the economics of image production change your perspective on it? Editor: Definitely! It reframes it from being simply a portrait of a notable person, to being a commentary on power structures, crafted through materiality and social practices of the time. It makes me want to consider art-making as labor itself, not just art object creation! Curator: Exactly! By considering the means of its production, the materials used, and the historical context, the piece becomes a social artifact reflecting its time. Editor: Thanks so much for pointing that out – I have a whole new appreciation for engravings now!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.