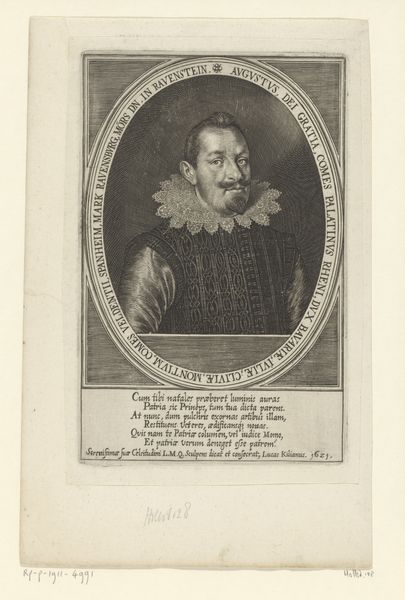

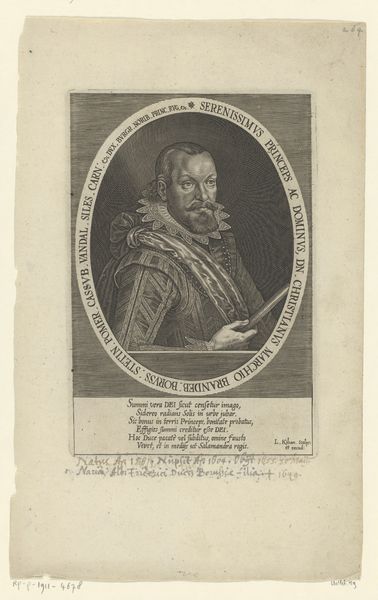

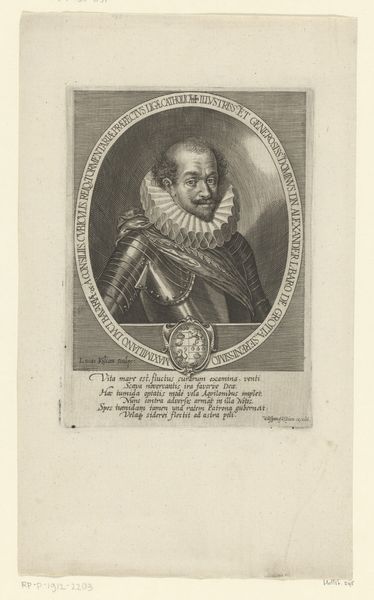

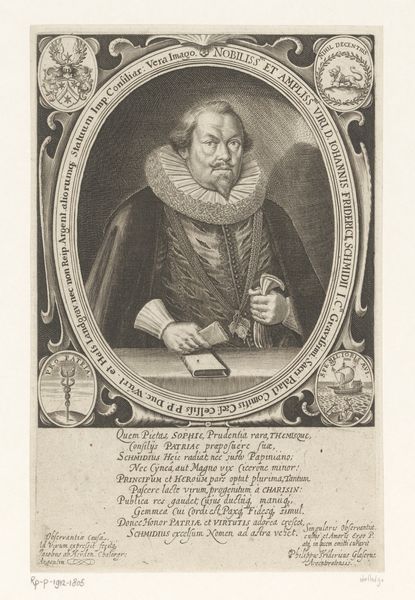

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 204 mm, width 139 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving by Lucas Kilian, "Portret van Christian von Anhalt-Bernburg" from 1615, is striking. I think it provides rich insight into early 17th-century society, don’t you agree? Editor: It really does. This print, with its formal inscription and armored figure, feels so stiff and official. It's interesting how such a mass-produced medium tries to project such power. What's your read on this? Curator: I'm immediately drawn to the materiality of the printmaking process itself. Consider the labor involved in producing the copper plate, the skills required to etch the image with such detail, and then the subsequent reproduction and distribution of these prints. Each step reveals a hierarchy, a system of production and consumption. Think about who would have been able to afford such a print, who controlled the means of its creation, and what that says about early 17th-century society? Editor: So, the value isn't just in the image of Christian, but in understanding who had access to creating and possessing such imagery? Curator: Precisely! The image of Christian serves almost as an advertisement, not only for him, but for the skilled labor and resources of his court. The engraving itself becomes a commodity, reflecting and reinforcing the existing power structures. Do you notice how the lines create a sense of texture and depth, attempting to mimic the richness of a painted portrait? Editor: I see that. It is trying to present something high end, while being more easily manufactured than painting. It almost cheapens it a bit, and makes it…advertising, like you mentioned. Curator: Yes! And look at the text surrounding Christian. Latin, indicating an educated elite audience, but also functioning as branding, associating him with nobility and even a divine right to rule. The production, dissemination, and consumption of this print reinforced this power. Editor: That really shifts my perspective. I was focused on the stern face, but it's more about who commissioned the work, who made it, and who consumed it. It shows who the powerful people were. Curator: Exactly. Thinking about these works in terms of labor, production, and material allows us to better understand not just the subject, but the social fabric of the time. I am glad you also learned to think about portraiture in the context of materials.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.