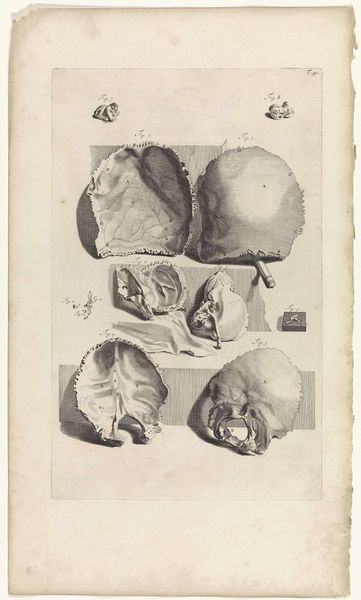

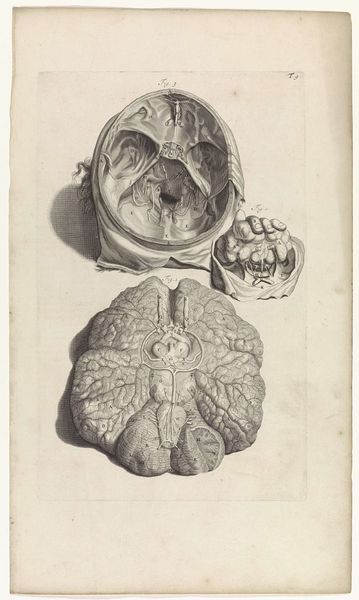

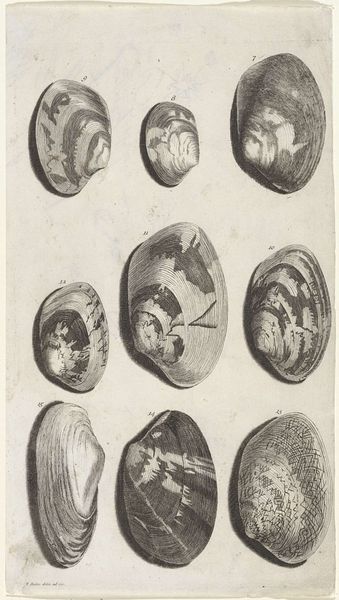

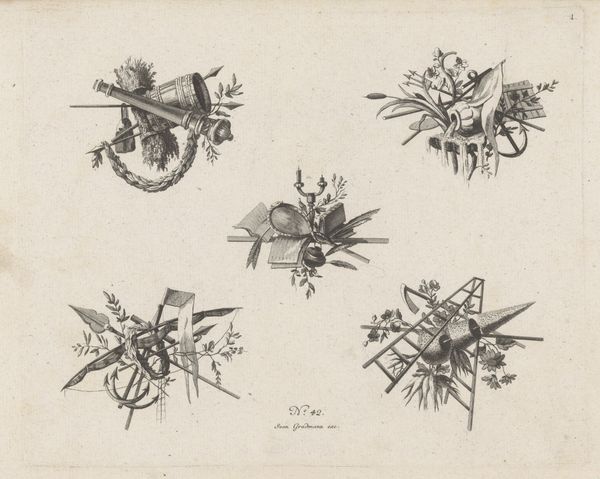

drawing, print, ink, engraving

#

portrait

#

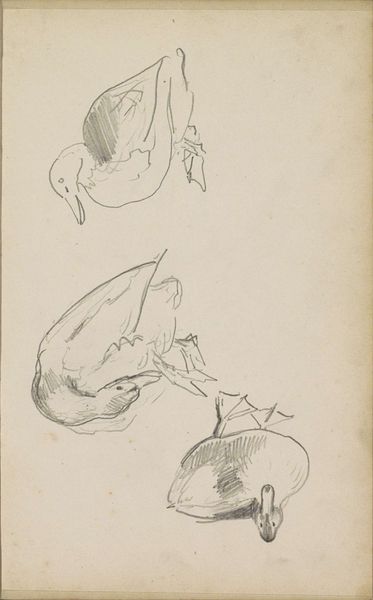

drawing

#

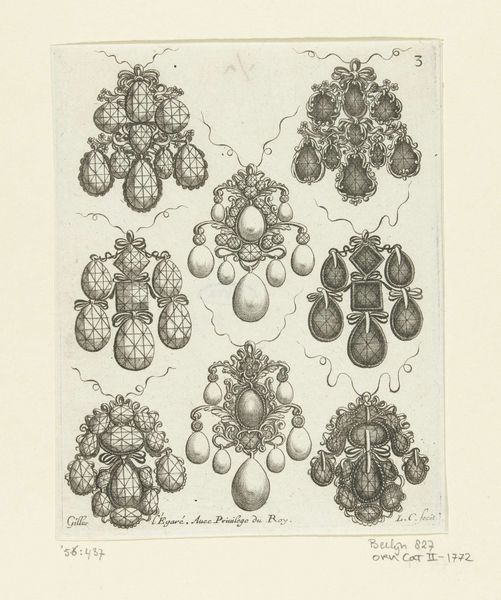

baroque

# print

#

old engraving style

#

11_renaissance

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 321 mm, height 467 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Well, that's... striking. There's something about the stark detail that is both fascinating and a little unsettling. Editor: This is "Anatomische studie van het oog," an engraving by Pieter van Gunst dating back to 1685. It's part of the Rijksmuseum's collection. And you're right; it definitely grabs your attention. Curator: It's the coldness of the medium, I think. Ink on paper, so precise, so devoid of warmth. You're looking at the mechanics of sight rendered with the detached eye of a scientist. The question that comes up is how was this piece produced? Editor: That's where it gets interesting. Prints like these weren't just about scientific accuracy; they served a vital purpose in disseminating knowledge at a time before widespread photography. It offered physicians, students, and interested public an unprecedented, if mediated, view of human anatomy. Think about it, these anatomical depictions provided valuable visual resources for education, advancing research and medical understanding across institutions. Curator: True, but the creation also has implications on artistry. The printmaking process is essentially reproductive work. Was van Gunst translating existing drawings or working from direct observation? What does this reproductive work mean in relationship to other fine arts or scientific illustrations? Editor: We can’t ignore how the very public nature of this kind of image shaped its production. It has implications far beyond science. Curator: Exactly! The institutional and societal desire for knowledge played a huge role, not just the artist's skill. Where would van Gunst present such pieces, besides medical texts? This question gives further exploration and thinking regarding its social value. Editor: And looking at this now, in a museum setting, centuries later, the context has completely shifted. We’re not using it to train surgeons. It's now an object of historical and artistic interest. Curator: It makes you appreciate the layers of meaning embedded in such a seemingly clinical work. There's science, craft, dissemination of knowledge, societal impact, all swirling around those meticulously rendered eyeballs. Editor: Indeed, it provides an exceptional overview of how society has always valued knowledge through artistic form and function.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.