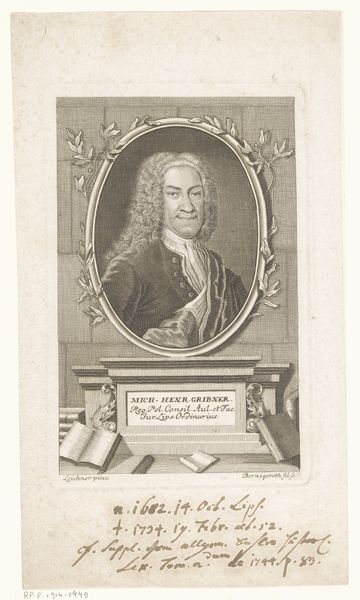

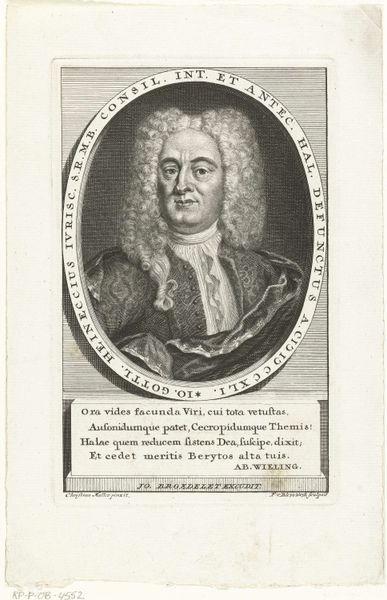

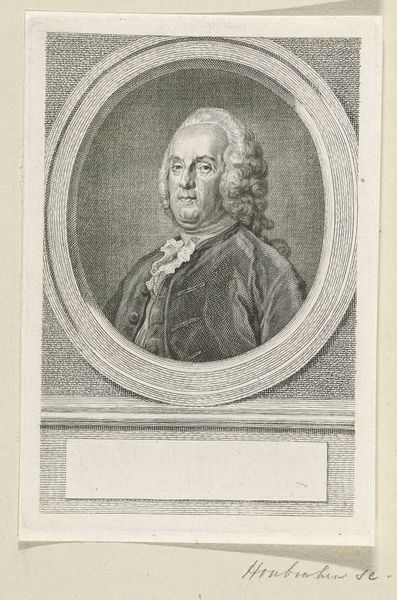

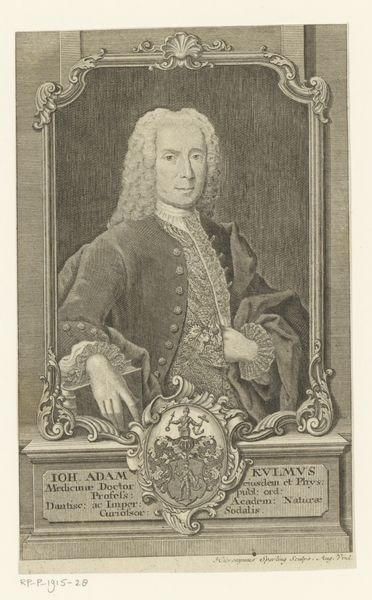

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

old engraving style

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 263 mm, width 172 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

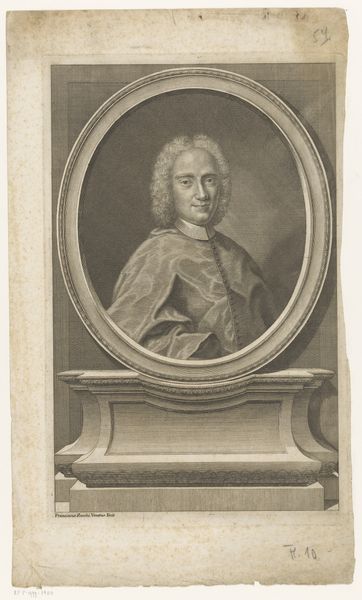

Editor: Here we have Jacob Houbraken’s "Portret van Johann Gottlieb Heineccius," dating from 1708 to 1780. It's an engraving, so a print, and the detail is just amazing. It almost feels like I'm looking at a photograph from that era, except that it's hand-crafted. What strikes you most about it? Curator: I'm drawn to how the materiality of this engraving speaks volumes about its cultural context. The very act of creating it through engraving – the labor, the tools, the social purpose of reproducing images – becomes the artwork itself. How does this portrait operate within the wider sphere of 18th-century print culture and its relationship to societal power? Editor: That's a good point. It seems so…formal, so official. Was it purely about commemoration, or was there another use of it at the time? Curator: Think about the materials: copper, ink, paper. These were commodities, circulating in a burgeoning capitalist market. The portrait wasn't just about preserving an image; it was about consumption, about disseminating an ideal of learned authority. Who was the intended consumer? Did the choice of engraving, over say, painting, have implications for access and affordability? Editor: So it's not just about *who* is portrayed, but *how* the portrait itself was produced, and how it was distributed that's important? Like, who could afford to purchase and display this kind of print? Curator: Exactly. We can also ask questions about the social function of such portraits. To what extent do they legitimize Heineccius’s position by presenting him in a format designed for mass circulation and consumption by a rising class of professionals and intellectuals? Editor: I see now. It’s fascinating to think about the materials themselves having a kind of voice. Curator: Absolutely, understanding the 'how' gives us a richer understanding of the 'why'. And perhaps, that offers us insight beyond this singular image into the values of 18th-century society itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.