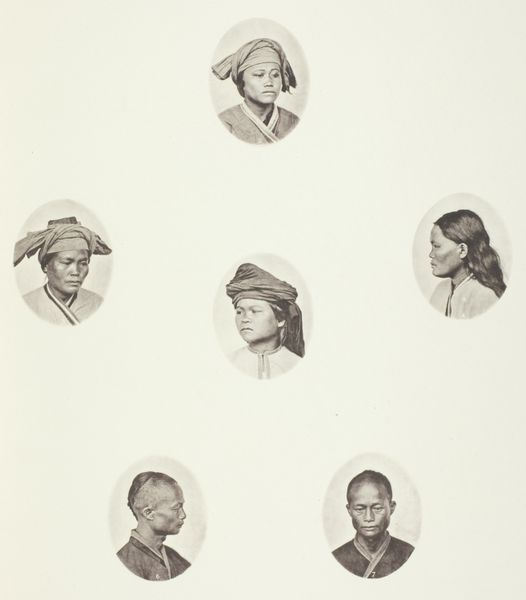

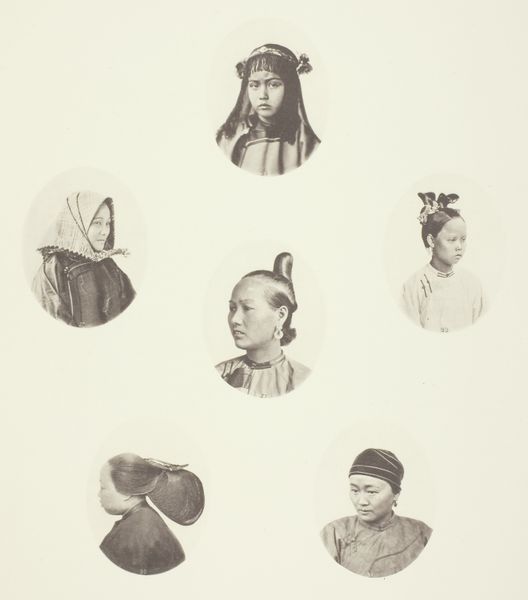

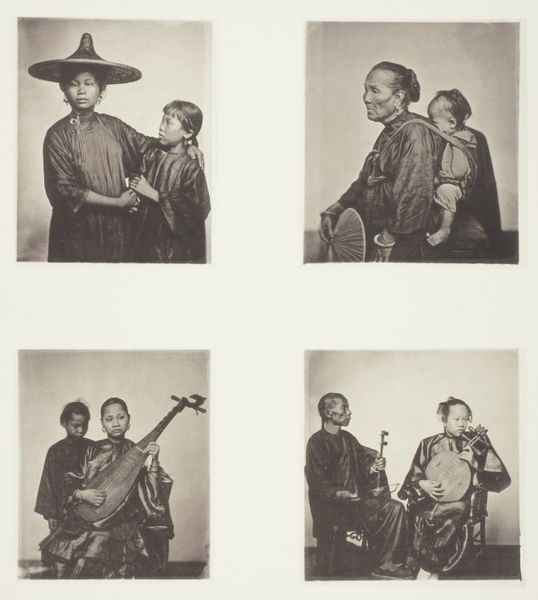

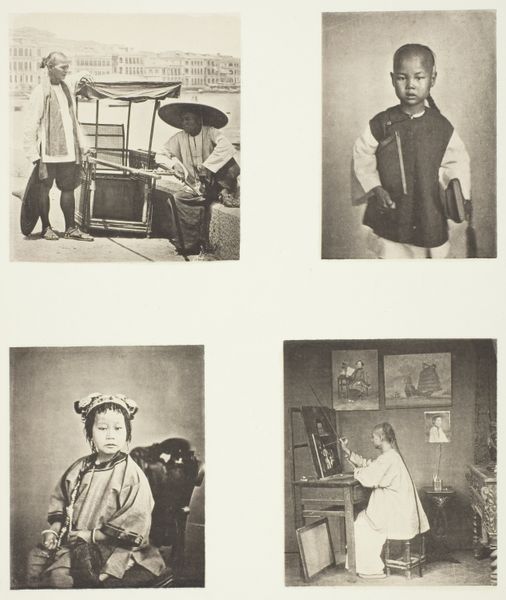

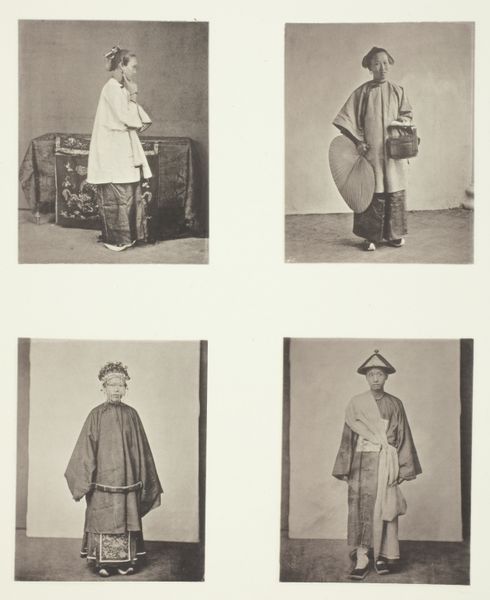

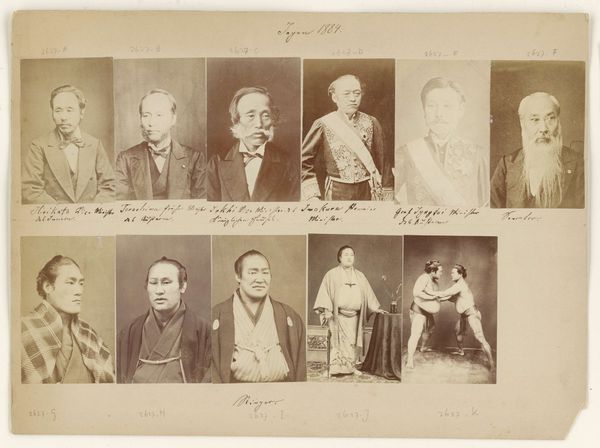

Cantonese Boy; Cantonese Merchant; Mongolian Male Head; A Venerable Head; A Labourer; Mongolian Male Head c. 1868

0:00

0:00

photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

asian-art

#

photography

#

genre-painting

#

realism

Dimensions: 7.8 × 6 cm (each image, oval); 47.1 × 34.6 cm (album page)

Copyright: Public Domain

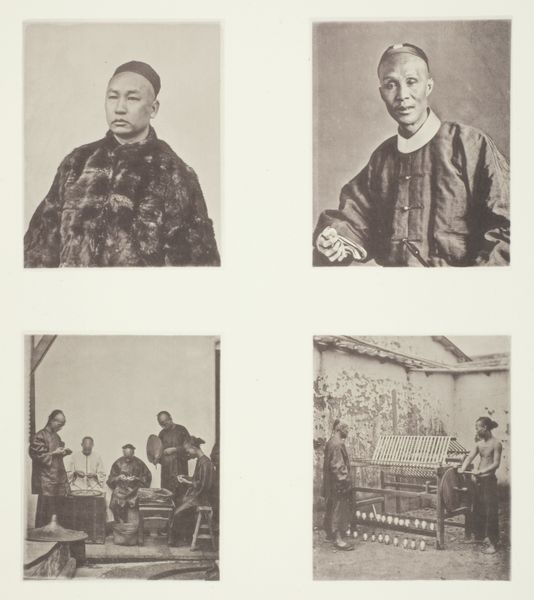

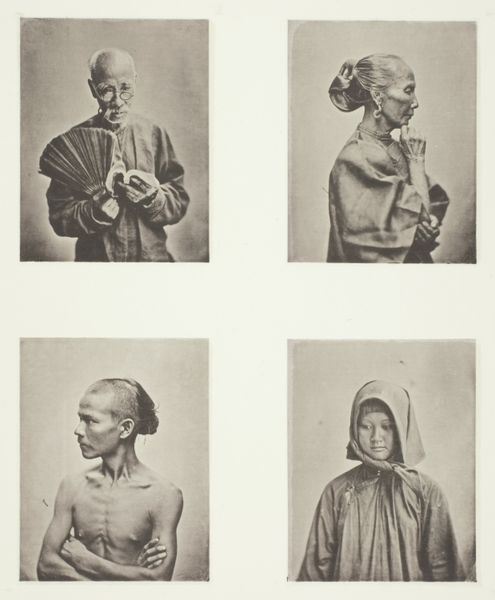

Curator: These portraits, collectively titled "Cantonese Boy; Cantonese Merchant; Mongolian Male Head; A Venerable Head; A Labourer; Mongolian Male Head", are brought to us by John Thomson from around 1868. He captured these individuals using photography. Quite a compelling display, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: Yes, the first thing that strikes me is the quiet dignity in each face. It’s a fascinating mosaic of ages and expressions, all framed in these neat oval vignettes, almost like collected botanical specimens, but of people. What was Thomson trying to capture here, do you think? Curator: Thomson’s work serves as a valuable visual document of 19th-century China, offering insights into its diverse population. In his role as a social observer, the identities denoted in the titles may reveal prevailing European attitudes towards professions and ethnicities at that time. This approach, where photography intersected with burgeoning ethnographic interests, aimed to categorize and understand a rapidly changing world through visual means. Editor: So it's both a document and, inevitably, a reflection of its time— a kind of colonial gaze frozen in silver. There's a real tension there, isn't there? I'm drawn to the older man with the distinctive queue. The lines on his face tell such a story, a stark contrast with the smooth innocence of the young boy at the top. It’s an incredibly diverse microcosm. Curator: The artistry lies not only in Thomson's technical skill, evidenced by the crisp detail achieved with the photographic methods of the time, but also in how he presents these subjects to his Western audience. Consider how such imagery shaped European perceptions of Chinese society, informing political, commercial, and cultural interactions. Editor: And, let’s not forget, affected the individuals in those societies being observed, documented, perhaps even exploited through this lens. But stepping back a moment, the arrangement of the portraits itself – that almost scientific layout. Did this influence how people viewed themselves? The performance of identity feels so intertwined here. Curator: Absolutely. The power dynamics inherent in image-making were at play, contributing to a narrative about China that was as much about European assumptions as it was about Chinese realities. Photography, still in its relative infancy, was a potent tool in constructing that narrative. Editor: Looking at this now, there's so much complexity. Beyond the historical weight, each face continues to resonate, whispering stories of lives lived. It asks more of us than to be passive observers. Curator: Indeed, it invites us to reflect not just on the subjects themselves, but on the historical forces that brought this collection of faces together, and on the ethical considerations inherent in the act of representation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.