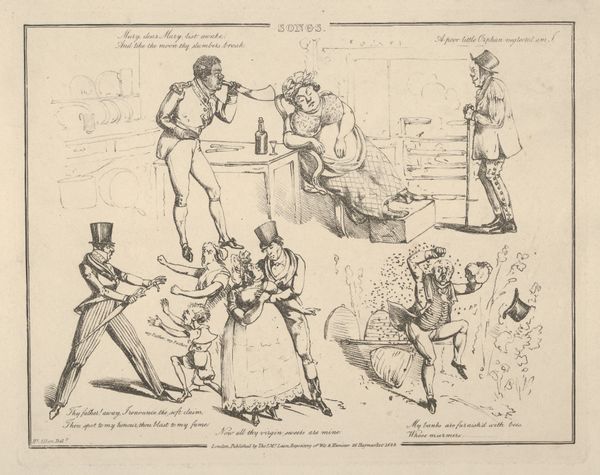

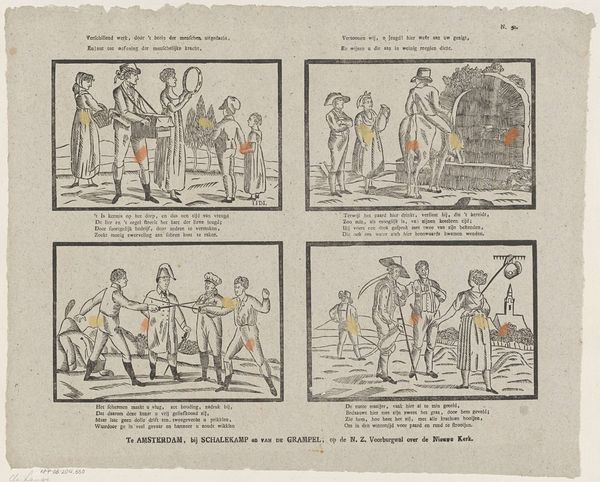

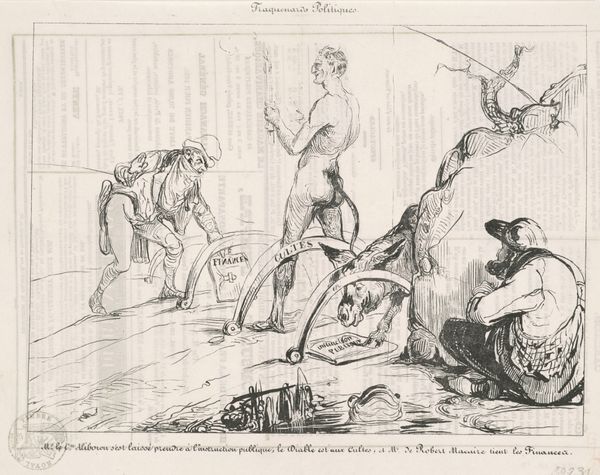

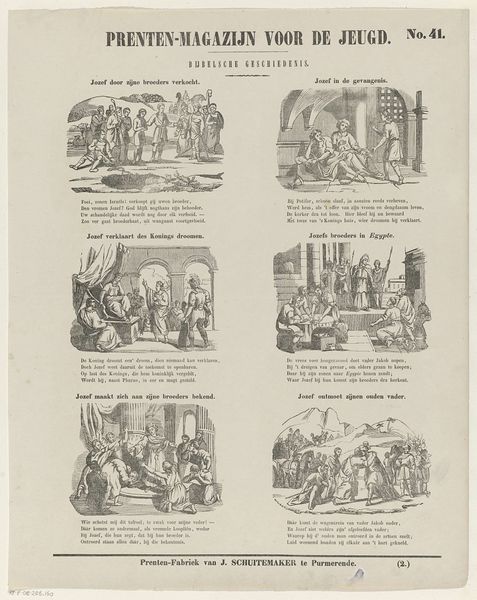

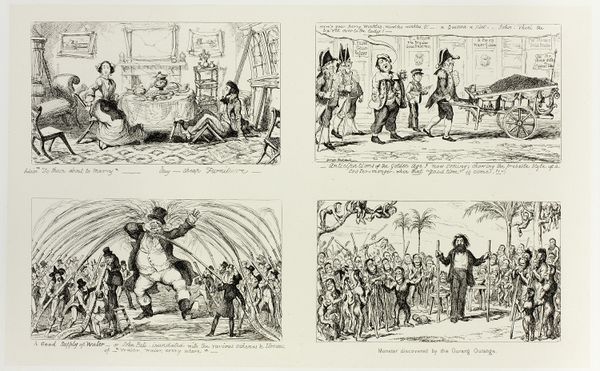

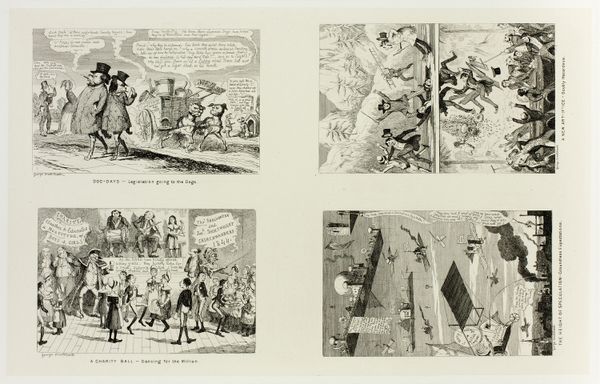

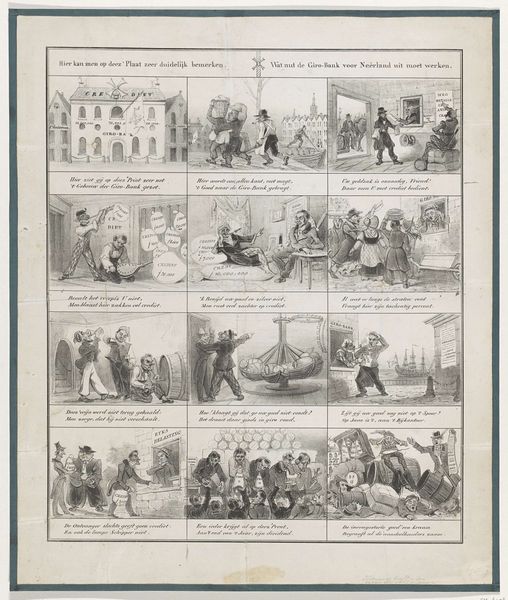

drawing, print, etching, ink, engraving

#

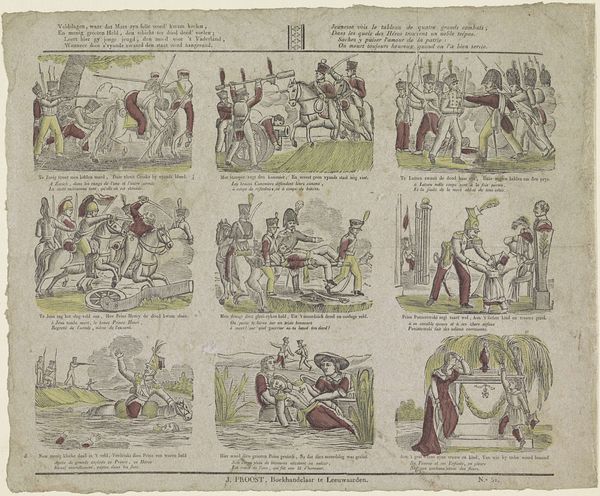

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

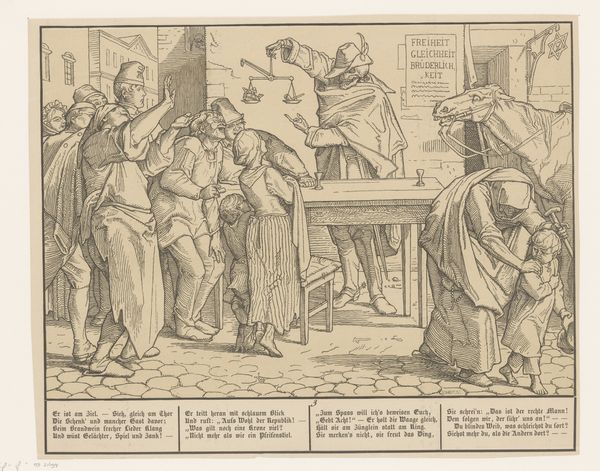

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

etching

#

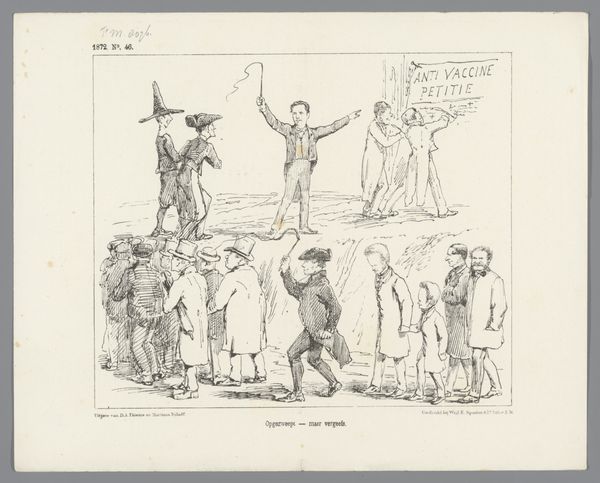

caricature

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: 306 mm (height) x 388 mm (width) (Plademål)

Curator: Salomon Savery's "Satire: Scatalogical subjects," created sometime between 1594 and 1678, invites us to delve into the scatological imaginings of the Dutch Golden Age. Savery used etching, engraving, and ink to create this narrative piece, now held at the SMK, the Statens Museum for Kunst. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the dense chaos. It's like a visual onslaught of bodily functions, with a comedic absurdity that's almost unsettling. The figures, rendered with such meticulous detail, are caught in various acts of… well, unpleasantness. Curator: Indeed. As a genre scene rendered with a high degree of caricature, the print functioned as a form of social commentary. The prominence of scatological themes reflected anxieties and obsessions present in early modern Europe. Think about the grotesque body in art history – the low and base realities, often depicted to undermine authority. Editor: I’m struck by the blatant social commentary, specifically as a vehicle for protest. We must consider class too—were such criticisms leveled only at the poor, reinforcing power structures, or was there a broader critique aimed at the elite, albeit masked in jest? Are we, the audience, meant to feel disgust, amusement, or perhaps both? Curator: Well, humor, especially of the bawdy variety, was often used as a subversive tool. Caricatures like these, widely disseminated through prints, allowed for a certain degree of public discourse, though undoubtedly within carefully policed boundaries. Its position, like much early modern satire, is fascinatingly ambiguous in that regard. We should also remember the role that prints and the printing press had on social movements as a way of disseminating news and promoting specific ideologies. Editor: It is fascinating how artists throughout time and across cultures use bodily functions to ridicule. Savery's work also suggests an interrogation of accepted behavior. How do cultural norms define what is 'acceptable' versus 'grotesque', and who has the power to decide? Perhaps “Satire” acts as an assertion, daring to show those allegedly “shameful” acts—like excreting bodily waste—thereby stripping away shame by showing that EVERYONE does them. Curator: Yes, considering who had access to these types of visual cultures would be crucial. How were these pieces viewed? Prints afforded them wide distribution, yes, but what happened with them after that is equally important. Editor: Thinking about it now, it almost feels… relevant, a reminder that even in the most 'civilized' societies, the human body and its functions are ever present. Thank you for pointing out all those contexts, it truly reshaped my point of view. Curator: My pleasure.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.