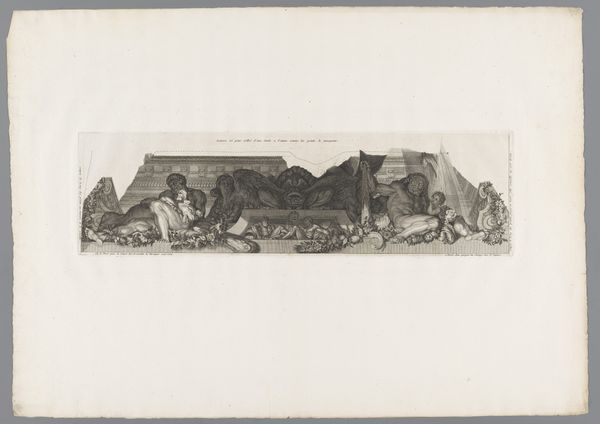

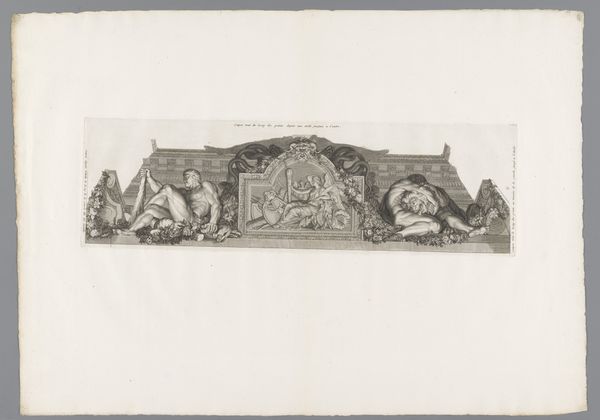

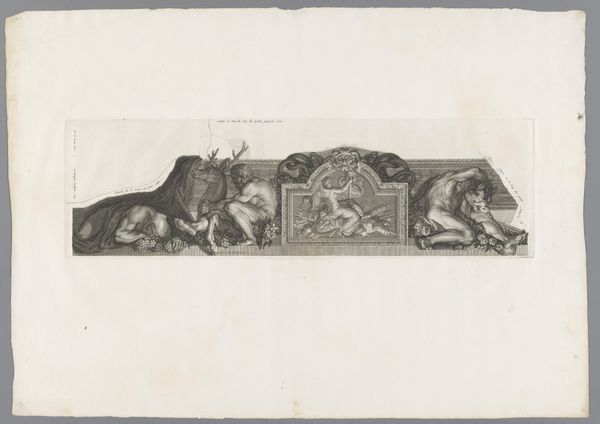

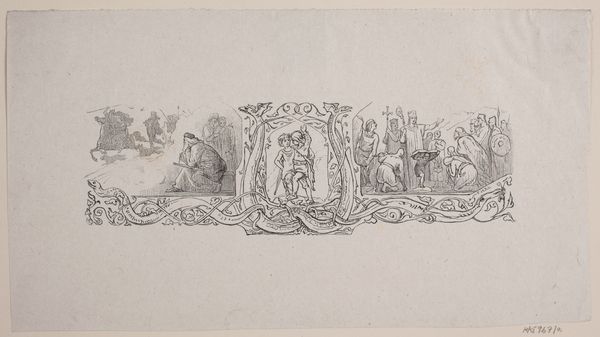

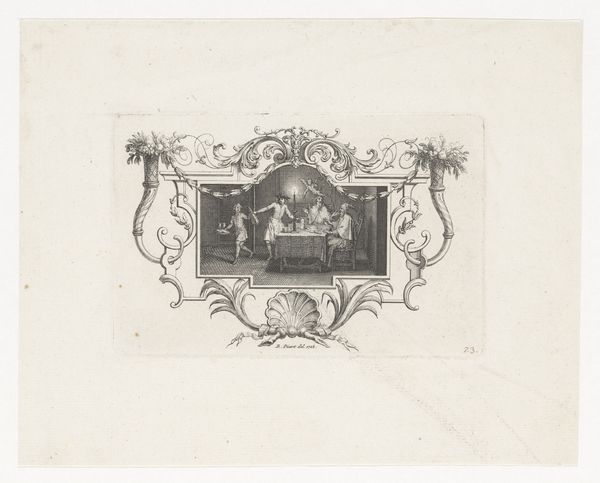

Reliëf geflankeerd door Hercules met de stier van Kreta en Hercules met een paard van Diomedes 1713

0:00

0:00

louissurugue

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

# print

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 160 mm, width 585 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This engraving from 1713, created by Louis Surugue, is called "Relief Flanked by Hercules with the Cretan Bull and Hercules with a Horse of Diomedes." It depicts scenes from mythology. I'm immediately struck by how incredibly detailed the figures are, especially considering it's a print. What can you tell me about it? Curator: Well, consider the laborious process of creating such an engraving. The artist, or more likely a workshop of artisans, painstakingly etched these lines into a metal plate. The scale of labor is substantial. Notice the recurring theme of Hercules, a figure known for his Herculean, literally, effort and triumphs over material challenges. Editor: That's a great point. The stories are about overcoming physical beasts, but the print itself is a product of intense physical work, right? It looks incredibly time-consuming to produce so many details, what are the steps in engraving process? Curator: Exactly! Engraving involves using a tool called a burin to cut lines into a metal plate, and how deep those lines are, determines the shading and level of contrast. How many people do you imagine worked on making prints with this design, at what different stages, and for how long each day? Who did the cutting, who made the ink? Also, consider where it was made and sold – was this print for a wealthy patron, a more middle-class audience, or as part of a larger book, like the many baroque illustrations printed around this period? What does the subject matter communicate about the relationship between labour, the materials of production and status? Editor: I hadn't thought about the number of people involved, and how they divided the work. So, reading it materialistically means moving away from only understanding the allegory in the image towards looking at what it tells us about labour practices at the time. Thank you, that’s so interesting. Curator: Precisely, it helps ground our interpretation in the real world of its production.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.