Dimensions: height 220 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

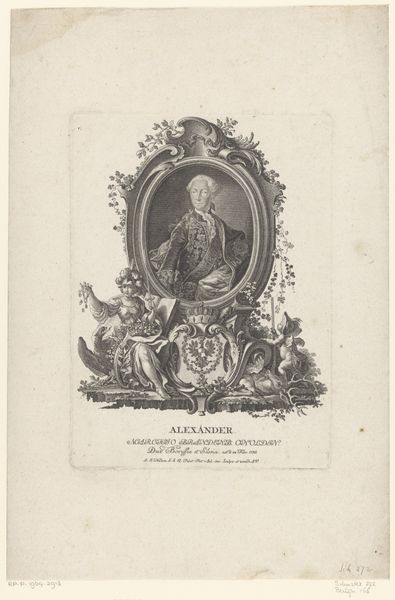

Curator: Johann Esaias Nilson created this engraving, "Portret van George III," sometime between 1760 and 1788. It’s currently held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has a very rigid feel to it. The sitter is surrounded by what appears to be a lot of political and divine iconography, the baroque framework is pretty ornate, and there are winged putti, military symbols and allegorical figures. Curator: Let's consider the materials and process. Engraving as a medium involves a labor-intensive process. Lines are cut into a metal plate, which is then inked and pressed onto paper. The repetition inherent in printmaking allows for the wide dissemination of the image and, by extension, the sitter’s authority. Who do you think it represents to those in power, then? Editor: An instrument of projecting the image of monarchy, absolutely. The presence of George III framed as if divinely appointed tells a very deliberate story of inherited power. I'm thinking about the implications of wide distribution, how access dictates reception. Was it designed to instill a particular sentiment of awe? Curator: The allegorical figures offer insights into the intended meaning. Note the female figure with her shield, representing British military power. She's coupled with chubby, playful angels bearing emblems of monarchy. How do these elements position George III? Editor: I read the ensemble of symbols as the calculated justification of the colonial endeavor and British imperialism. A suggestion, almost, of divine endorsement legitimizing actions under royal purview. What does the process of academicizing mean when applied to this form? Curator: The print situates itself within the framework of history-painting, referencing earlier styles, though it's primarily a portrait. It's not attempting to represent anything particularly revolutionary but a well-established regime. Academicism ensured consistency and perpetuated the ideals of the ruling class by disseminating their views through imagery such as this, that were quite common at the time. Editor: I see it. Looking at this through a contemporary lens, I cannot separate this object from my understanding of history and continued global consequences— particularly around trade— of 18th century imperialism. Curator: Understanding the intention, and the medium in its own context is essential when interpreting it. Even today, examining its visual vocabulary can bring insight to the role of imagery in solidifying power structures. Editor: Indeed. Studying images such as these allows us a glimpse into the production and performance of power, which can make that currency legible in other historical and contemporary contexts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.