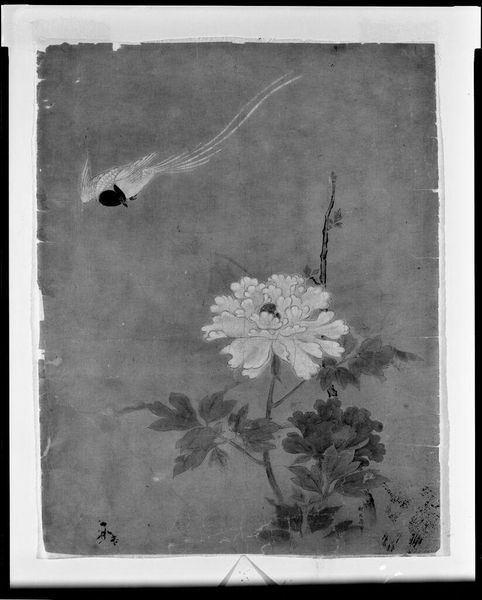

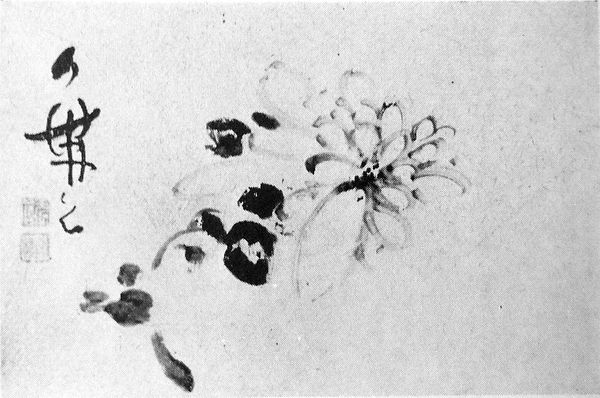

drawing, ink

#

drawing

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

ink

#

orientalism

Dimensions: 10 7/8 x 14 1/2 in. (27.6 x 36.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Welcome. Today we’re looking at "Bellflower," a drawing attributed to the Hokusai School, dating roughly between 1800 and 1868. It’s rendered in ink and currently held here at The Met. Editor: The first impression I get is one of such stillness. It's quiet, almost melancholic. The flowers seem heavy. Curator: Absolutely. Let’s delve into that "weight." Notice the meticulous inkwork— the controlled brushstrokes creating the petals' textures and the varying densities that give depth. These gradations in tone aren't accidental; they reflect the craftsman's mastery. What's significant to me is that Ukiyo-e wasn't just some detached art form but a means of production that linked artists and their workshops to society’s consumer demands. Editor: I am struck by these flowers themselves—Bellflowers often symbolize gratitude and honesty in the Victorian language of flowers, but in Japanese culture, do they hold a particular significance? It seems to represent not just the aesthetic appreciation of nature, but perhaps some moral reflection of the values or even impermanence of things, considering the flowers’ brief lifespan and how they eventually wilt. Curator: A relevant interpretation, however, remember this piece may have been intended for wider reproduction as opposed to direct consumption as ‘high art’— mass production, via printing methods for example, shifted the intent towards widespread consumption in the booming economies and markets. That fundamentally recontextualizes the symbolism somewhat. The flowers themselves become part of that overall material process. Editor: I agree, although it appears quite meditative at first glance. But even appreciating that context, you see this contrast of detailed portrayal set against such empty space…the bellflowers retain cultural power as an enduring motif of beauty but maybe, as you mention, not purely. Curator: Exactly. Its simplicity masks the complex socio-economic reality of its making. The piece is, itself, part of an evolving exchange relationship – an act of economic activity in many ways as much as of pure artistry. Editor: So perhaps instead of a wistful mood, we find it speaks volumes about social values in this particular manufacturing time period. Thank you. Curator: Thank you; a crucial reminder that cultural context shapes our understanding of aesthetics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.