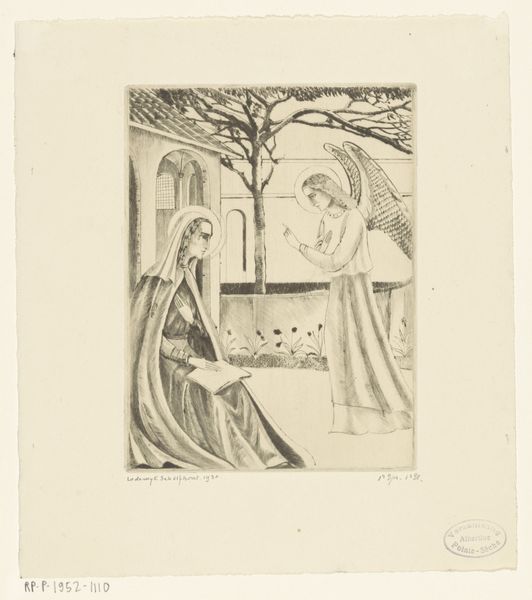

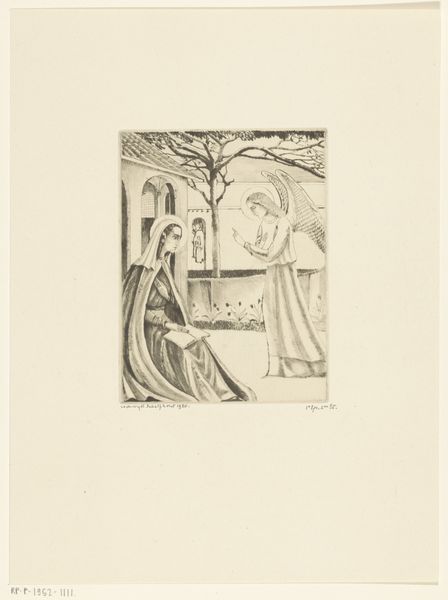

drawing, paper, pencil

#

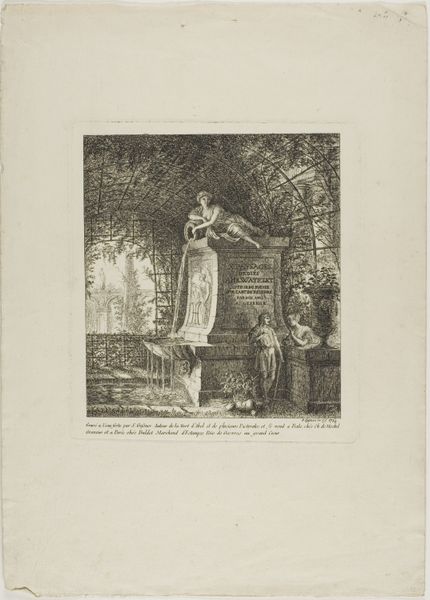

portrait

#

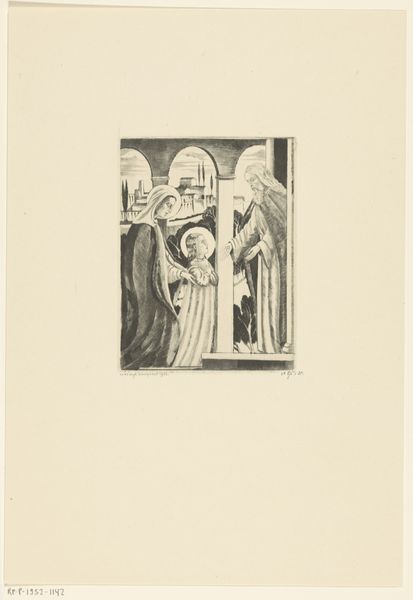

drawing

#

paper

#

geometric

#

pencil

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 158 mm, width 120 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

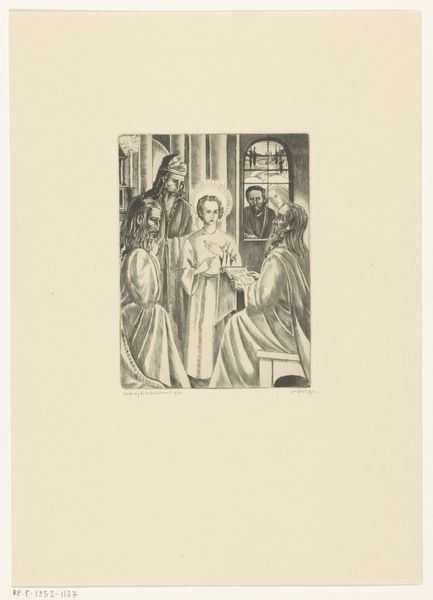

Curator: Upon entering the gallery, you'll encounter Lodewijk Schelfhout's "Marriage of Mary and Joseph," created in 1931. It’s a drawing done with pencil on paper and currently held in the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It has such a quiet, devotional atmosphere, almost like a faded memory rendered in muted grayscale. There’s a sense of solemnity evoked by the figures in prayer, framed by what appears to be Gothic arches. Curator: Indeed. Consider the deliberate use of pencil—a humble material for depicting such a revered scene. This elevates the labor, challenging traditional distinctions of sacred versus ordinary, drawing versus painting. Also, note the paper itself; what was available for the artist to use and how accessible? Editor: Absolutely. And beyond the material composition, I'm struck by the social commentary embedded within. We are looking at an unequal power structure upheld within traditional religious contexts and reinforced through gender roles, the marginalization of the feminine—Mary depicted almost passively—and the silent consent in their betrothal. Curator: Interesting angle. The geometric quality is remarkable as well. Look how each element - the architecture, the candlelight, the halos, reinforces linearity in the composition. One must remember it was created around the Depression era; rationing would apply to any material he might acquire. How does he make the best with so little, and still create such a vivid, yet muted, expression of marriage, love and tradition? Editor: I’d push back slightly, considering its historical setting within increasing sociopolitical tensions in Europe leading up to World War II. What's not spoken in the representation of Mary and Joseph’s relationship speaks volumes about prescribed roles, enforced piety, and cultural expectations. We must examine religious iconography for how it perpetuates not only faith but certain social standards. Curator: Yes. In summary, the piece isn't just about a Biblical marriage; it prompts reflections on artistic means of production and their sociohistorical roots. Editor: Exactly, which invites deeper consideration of how images like this, even in their quiet stillness, participate in wider dialogues on power, faith, and gender relations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.