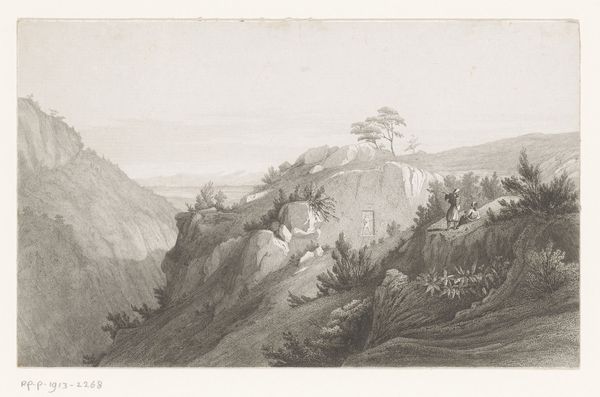

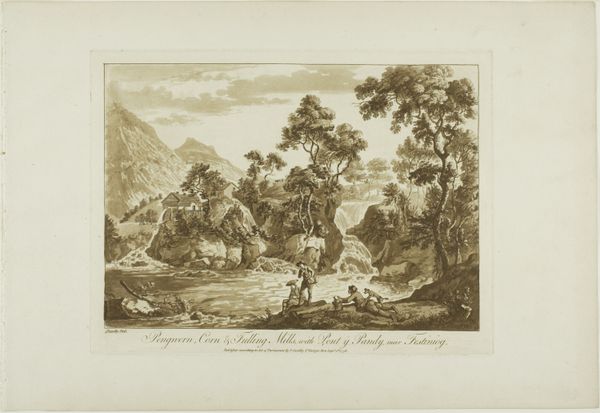

Dimensions: height 101 mm, width 145 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have Heinrich Rieter’s 1782 work, "Herder voor een grot te Montcherand," rendered in watercolor and pencil. There's such a stillness to it, a quiet reverence for the landscape... Almost melancholic. What do you see in it? Curator: Oh, melancholy for sure! But for me, it's the quiet kind that invites you to sit with it. It’s like Rieter’s whispering secrets of the Romantic era, where nature wasn't just scenery; it was a mirror to the soul. The muted tones, that lone shepherd – do you think he's content, or lost in thought? Editor: I hadn't considered the shepherd’s emotional state... Maybe a little of both? There’s something lonely about that cave, yet he’s chosen to be right beside it. Curator: Exactly! That's the Romantic paradox. A longing for wildness and solitude, while simultaneously needing connection. See how the cave isn't just a backdrop, but a looming presence? Nature was often used to symbolize power that was so often sought after during that time. Editor: That contrast makes it feel so much more dynamic. It's not just a pretty picture. How does his use of watercolor influence this? Curator: Ah, the watercolour. It gives everything this ethereal quality, like a half-remembered dream. With that thin layer it evokes something so soft and light. Imagine if it were an oil painting? Entirely different mood, I wager. What would you say it does to the sense of immediacy? Editor: Good point. The immediacy is lost; maybe it makes us reflect on the present by drawing us deeper into Rieter’s own introspection. I hadn't considered how much the medium impacts that. Curator: Precisely. And isn’t that the beauty of art? It's a dialogue across centuries. Rieter whispers, and we listen… Editor: That’s certainly changed the way I look at it. So much more there than meets the eye at first glance!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.