engraving

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

baroque

#

charcoal drawing

#

charcoal art

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 319 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

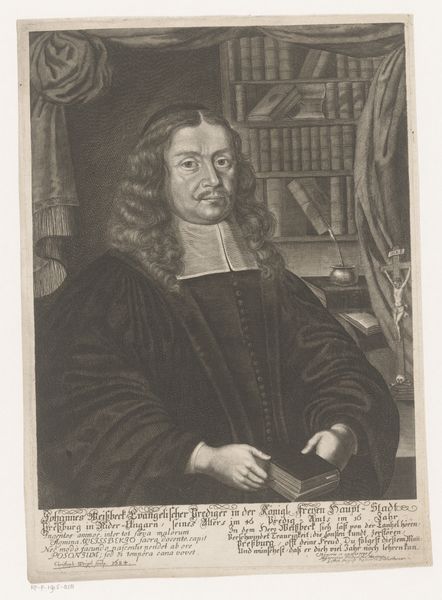

Curator: Here we have Tobias Laub’s "Portret van Johann Jakob Scheuchzer," created in 1731. The engraving on view here at the Rijksmuseum offers us a fascinating glimpse into the life of the titular subject. Editor: My first impression is one of studied seriousness. The textures created with engraving are quite interesting - especially the juxtaposition of the heavy velvet robe with the delicate objects laid out on the table. Curator: Absolutely. I’m particularly drawn to how the labor of producing engravings like this—replicating images for wider circulation—shaped perceptions and access to knowledge in the 18th century. The print served not just as a portrait but also as a tool for constructing Scheuchzer’s public persona and bolstering his scientific authority. Editor: And consider the visual politics at play. The choice of including natural specimens—the shell, the fish, the plant—connects him directly to the burgeoning scientific discourse of the time and his encyclopedic knowledge. We see this through the lens of what was considered a scholarly gentleman of the period. Curator: Indeed. The composition directs our gaze, focusing on his hand gently placed near those specimens— a visual anchor connecting the man, the objects, and the book. Each element crafted with careful and precise use of the engraving tools. The work becomes evidence of skillful artisanal labor, effectively mimicking the tactility and substance of skin, cloth, and nature itself. Editor: You bring up an excellent point regarding this image as evidence, not only of craft but also as a demonstration of societal power structures that favored certain individuals, classes and intellectual pursuits above others, and which institutions reinforced those hierarchies. Who would see this? Where would it circulate, and how would it contribute to shaping perspectives on science and the natural world in Europe? Curator: I hadn’t considered that angle as closely as you, but seeing how it portrays science is quite telling about the dissemination of knowledge. Editor: It's interesting to consider how these portraits circulated and served to solidify reputations. Each time this print was made and distributed it would enhance the power structures. Curator: Well, thanks to our time looking more deeply at the "Portret van Johann Jakob Scheuchzer," it highlights the impact of material culture. Editor: And it reminds us how historical portraiture served, both subtly and overtly, to affirm particular social roles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.