drawing, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

ink painting

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

figuration

#

paper

#

ink

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Copyright: Public Domain

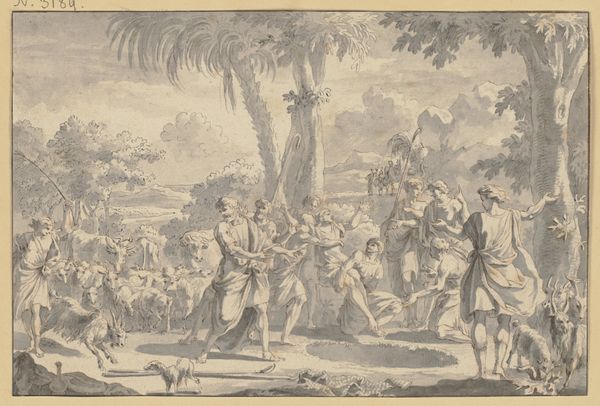

Curator: Looking at "The Adoration of the Golden Calf" by Claude Lorrain, created around 1653, I'm struck by the sheer density of the etched lines; it creates such a busy, frantic feel to the scene. Editor: Indeed. Knowing this piece is held at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt allows us to consider the socio-political lens through which the German public, then and now, might view the biblical story it represents. The choice to depict a chaotic crowd around this idol directly engages with questions of morality, social order and cultural identity, no? Curator: Absolutely. And looking at the materiality of the work - ink on paper, rendered through etching - highlights how Lorrain reproduced and disseminated this image. This was a method of producing art for a wider consumer base, challenging the exclusive nature of painting. We must ask, who was this made for? Editor: Precisely. The etching medium itself becomes part of the message. It made it accessible. Further, consider how depictions like this one played within the 17th-century political and religious landscape, specifically the power dynamics between various factions vying for influence and validation, even subtly commenting on contemporary institutions. Curator: It’s amazing how the medium facilitates his style; the swirling lines create depth and motion despite the stillness inherent in a printed image. It reminds us how the artist controlled not just the narrative, but also the physical production and replication, affecting its market value and broadening appreciation. Editor: And note the framing - Lorrain is positioning the viewer within the landscape, encouraging reflection. The composition urges viewers to examine how social pressures might lead communities to embrace transient beliefs. I mean, are there ways to contextualize the figures on display here with various types of contemporary corruption? Curator: That’s provocative. Reflecting on the physical act of producing so many lines and on his possible commercial goals highlights an interesting conflict in the narrative he has captured here, the complex interaction of devotion, commerce and the image economy. Editor: Well put. This deep-dive encourages thoughtful consideration, bridging the artistic mastery of the individual with wider historical contexts. Curator: Yes, it underlines the significance of not only the artwork itself but also the choices the artist made in making the work accessible through its manufacture and mode of dispersal. Editor: Agreed. I hope it leaves our audience eager to delve into similar explorations.

Comments

stadelmuseum about 2 years ago

⋮

The composition of this drawing appears harmonious, although it corresponds only to the left side of Claude’s “Landscape with the Adoration of the Golden Calf”, which he painted for Carlo Cardelli in 1653. Concerning his figures, Claude took his cue from Raphael – according to the impressive format of the painting and the biblical theme – and closely followed his “Adoration of the Golden Calf” in the loggias of the Vatican. As his paintings became larger and their themes more demanding, Claude became less and less inspired by the works of his former colleagues from the North. By the beginning of the 1640s he was increasingly influenced by Domenichino, Nicolas Poussin and Annibale Carracci, but above all by Raphael and his pupils. In the completed painting for Cardelli, the group of worshippers has been rearranged, the altar moved to the left, and a group of dancers has been added to the right. The landscape of the painting is also completely different. Claude placed the group in the Frankfurt drawing in a pastoral landscape that has little in common with the desert of biblical history. In keeping with his habit of combining the figures of one picture with the landscape of another, he took the background of this drawing from a sheet in “Liber Veritatis” (MRD 460) copied from a “Landscape with Dancing Satyr” from 1641. The Frankfurt drawing thus seems like an independent composition that goes directly back to Raphael’s painting. It cannot be ruled out that it played a role in the early stages of the composition, but it is curious that the background shows so little interest in the biblical text.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.