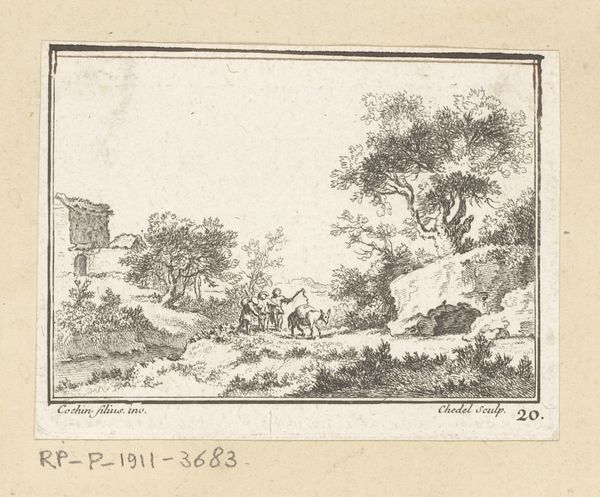

drawing, engraving

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

landscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 65 mm, width 82 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Landscape with a Ruin on the Right," created between 1725 and 1763 by Quentin Pierre Chedel, an engraving currently held at the Rijksmuseum. It strikes me as melancholic, the ruined structure hinting at a lost grandeur, now reclaimed by nature. How do you interpret this work? Curator: What interests me most is Chedel’s process. Think about the labor involved in producing this image. The metal plate itself, the tools, the precise hand movements required for each line… it all speaks to a complex system of production and consumption in 18th-century Europe. Consider the engraver's role – not just as an artist, but as a skilled worker embedded in a particular socio-economic context. What materials were available? Who commissioned the work? Where was it intended to be sold and circulated? Editor: So, rather than focusing on the aesthetic beauty of the ruin, you're drawn to the more practical aspects of its creation? I hadn't really considered that angle. Curator: Exactly. The "beauty" itself is a product of labor, of available materials, and of specific economic structures. The image reproduces and thus perpetuates power structures. Think about the relationship between landscape art and land ownership, or the emerging print market's impact on the dissemination of ideas. These landscapes romanticize an era built by exploitation. Is there a tension between the romanticism of the ruin and the harsh realities of the society that produced both the ruin and the print itself? Editor: That's fascinating! It definitely changes my perspective. I was focused on the emotional impact of the image, but now I see how much the materials and context contribute to its meaning. Curator: Precisely! The artwork is not an isolated object, but a nexus of social and economic forces. Editor: Thank you. I learned how material conditions inform artistic expression, going beyond immediate impressions. Curator: And I got to reiterate the significance of considering labor and production, which are all-too-often absent when looking at works of art.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.