Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

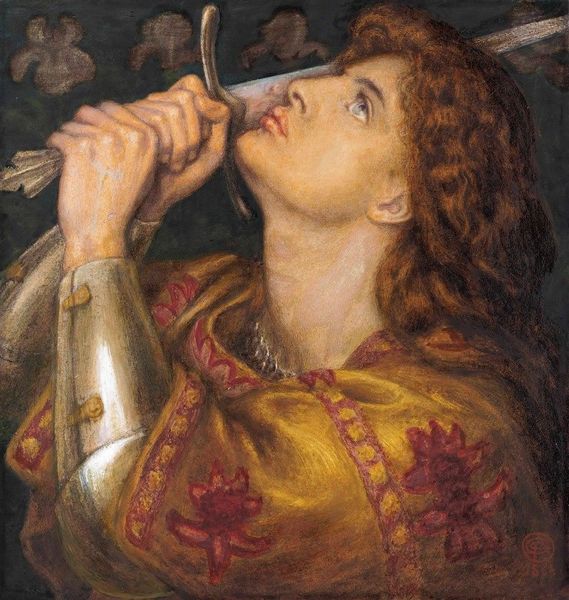

Curator: Let’s take a look at Ingres’ "Mars," created in 1864 using oil paint. It’s a study, actually, showing the god of war looking upwards. Quite an intense gaze. What's your initial feeling about this piece? Editor: The word that springs to mind is 'anguish'. He’s so young, but something troubles him. Is he looking up at divine judgment, maybe? I also notice the muted tones - a bit melancholy for the God of War, isn’t it? Curator: Yes, well, this wasn’t intended as a standalone artwork, more as preparation for a larger history painting. That muted palette is characteristic of Ingres, drawing from classical sculpture, emphasizing form and line over flamboyant color. Remember his Neoclassical training placed importance on the moral lessons that history and myth provided to public. Editor: Moral lessons... Right, and that hand above the helmet clutching… what? Is that a broken sword, maybe? He looks resigned, almost defeated, despite being Mars. Makes you question the glorification of warfare. Curator: Perhaps Ingres subtly undermined that glorification. He presents a thoughtful, even vulnerable Mars, challenging the traditional image of unbridled aggression we see associated with war. His positioning within academic debates about how the canon shapes our view is critical to note, actually. The art world shifted a few years later after this, too, towards newer subjectivities and aesthetic movements. Editor: Absolutely. And while steeped in historical art, Ingres seems to use his classical restraint to show the human cost hidden beneath the veneer of myth. Even in this brief, preliminary piece, one sees Mars’ inner conflict. It asks a very complex question. Curator: Which is exactly the kind of tension that continues to make Ingres relevant. His engagement with tradition was anything but straightforward, prompting us to rethink what classical really meant to the mid-19th century. Editor: Makes you think twice about your preconceptions, doesn’t it? A tiny brushstroke in the theatre of war’s historical interpretation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.