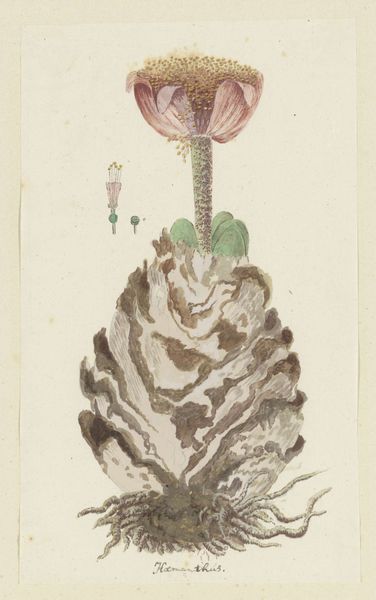

Dimensions: height 660 mm, width 480 mm, height 311 mm, width 199 mm, height mm, width mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

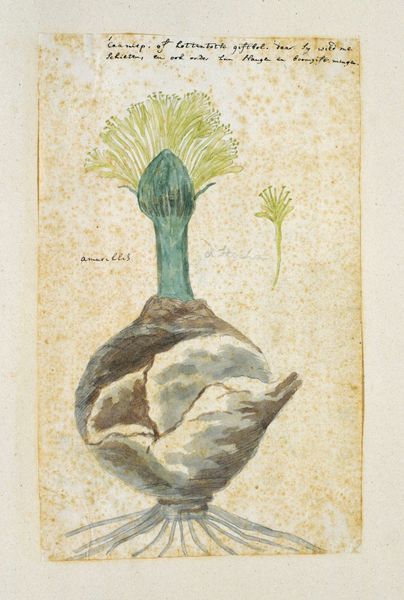

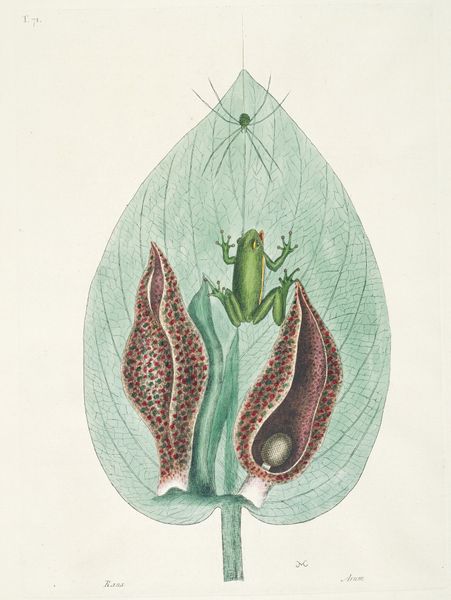

Curator: Here we have a watercolor and drawing from possibly between 1777 and 1786, attributed to Robert Jacob Gordon. It’s a study of the *Haemanthus coccineus L.*, commonly known as the Blood flower or *Bloedblom*. Editor: It’s rather striking, isn’t it? The way the artist captures the almost brutalist structure of the bulb with those fleshy leaves—and then the delicate burst of the flower itself. There's a distinct sense of the exotic captured here. Curator: Absolutely. Gordon, as a military man and explorer working for the Dutch East India Company, would have encountered this species firsthand during his expeditions in the Cape region of South Africa. This drawing isn't just a botanical record; it's a product of colonial encounter. The very act of depicting and classifying nature was bound up with asserting control over territory. Editor: I am immediately drawn to that blood red hue, like captured sunlight, bursting from what could otherwise be quite a drab package. That crimson carries powerful associations—life force, sacrifice, danger. Does the artist subtly play with this symbolism, you think? Curator: Quite possibly. Romanticism was just budding, after all. We often see botanical illustration serving empire, classifying and rendering docile the natural world for commercial use back home. But there is undeniable care given here to texture and color – beyond purely scientific purposes. Editor: Consider the title itself—*Blood Flower*. It suggests an awareness of the potent, symbolic value of the plant beyond simply a cataloging of a species, perhaps even preying on colonial anxieties, speaking to fears that even the botanical world can be dangerous. I see cultural anxiety mirrored in nature’s mirror. Curator: It also has roots, quite literally, in European trade networks. Specimens would have been collected and sent back to Europe, influencing botanical gardens and scientific study—shaping perceptions and even economies around natural resources. Gordon’s painting occupies an interesting place in that history. Editor: It speaks volumes about our complicated relationship to nature – its beauty and power and our ongoing quest to catalogue, consume, and sometimes conquer its riches. Curator: Indeed. And in a time where environmental narratives are crucial, returning to these early depictions is important if we want to trace how we came to regard nature in the way that we do now.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.