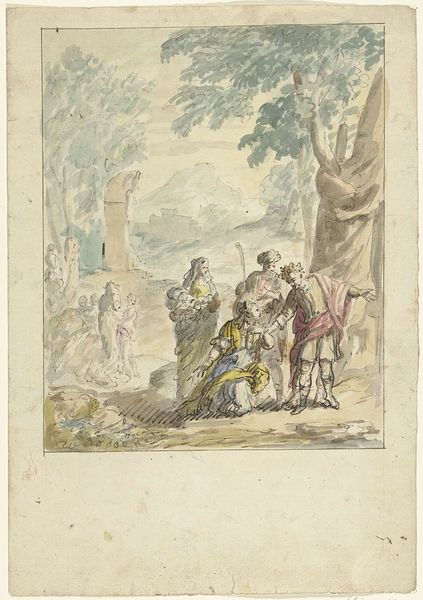

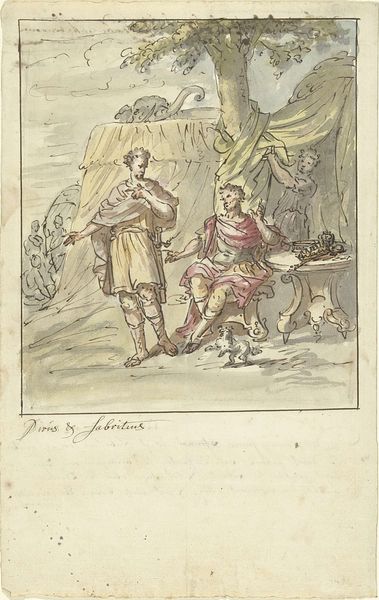

drawing, paper, ink, pen

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

#

baroque

#

paper

#

ink

#

pen

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

Dimensions: height 330 mm, width 210 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Elias van Nijmegen's pen and ink drawing, “Rebekka geeft Eliëzer te drinken,” made sometime between 1677 and 1755, captures a pivotal scene. The use of pen and ink on paper lends itself to fine details, yet a limited color palette imbues the artwork with simplicity. Editor: My first impression is one of subdued elegance. The artist’s hand is apparent, with delicate lines shaping the scene and soft colors hinting at classical influences. I see Baroque tendencies in the architecture behind the figures and the flowing robes of the figures, yet the use of light and shadow is stark. Curator: Considering that period, the story originates from Genesis 24, in which Abraham sends his servant Eliezer to find a wife for his son Isaac. Rebekah's act of offering water not only to Eliezer but also to his camels signifies her virtue and kindness, making her the chosen one. We can read into this drawing notions of duty, fate, and perhaps even proto-feminist ideals through Rebekah’s agency. Editor: Looking at the production, the materials and the method speak of accessibility. Pen and ink drawings such as this one allowed for wider circulation of biblical stories, as the printmaking of this piece would be simpler to reproduce in books. It highlights a specific function for dissemination of ideas, where biblical virtue is made available in homes that want moral instruction. Curator: That brings an interesting consideration to the reading of such stories for audiences today. The artwork, as a historical object, prompts us to question representations of women and servitude—what are the power dynamics at play in this narrative, and how might contemporary readings challenge or subvert them? Editor: Exactly! This artwork, though depicting a biblical story, offers material evidence of shifting class dynamics and the rise of the book. By bringing such aspects to light, we reveal so much of history. Curator: Exploring the intersectional elements helps unveil nuanced meanings that might have been overlooked in traditional interpretations. The piece makes you consider class, labor, gender, and moral education that reflects shifting socio-economic structures of the Dutch Republic. Editor: This discussion sheds light on how even seemingly straightforward works of art have complex origins. Considering production and disseminating this piece helps me view art not just as an aesthetic creation but as evidence.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.