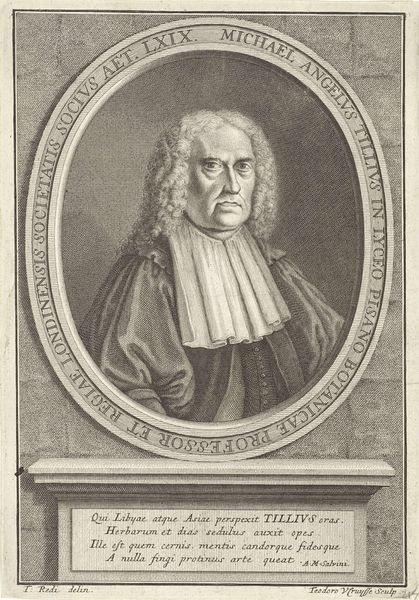

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

old engraving style

#

historical photography

#

northern-renaissance

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 355 mm, width 259 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

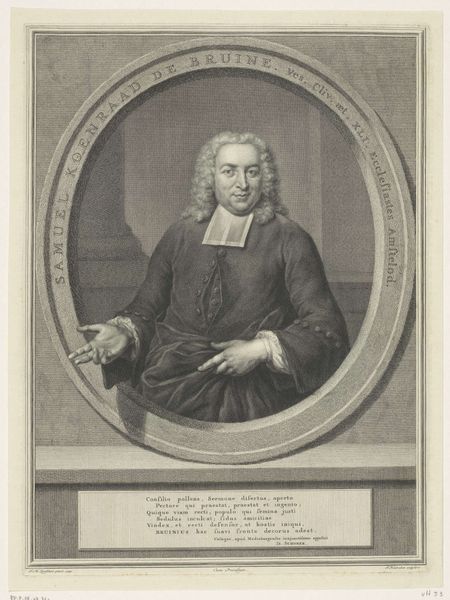

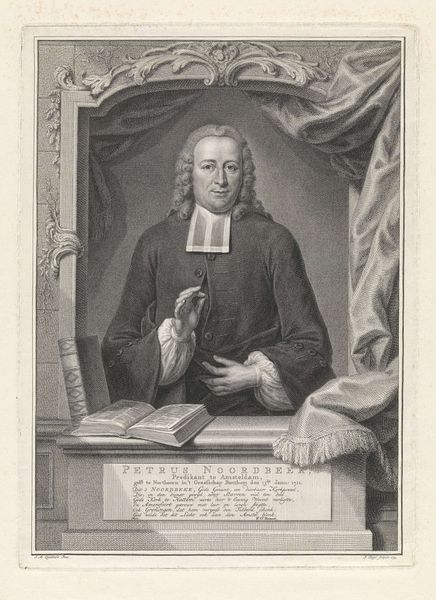

Curator: This is "Portret van Johannes Boskoop," an engraving by Jacob Houbraken dating back to 1755. It currently resides at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It strikes me as very composed, almost theatrical, wouldn’t you say? There's something about the setting – it frames him so precisely, it gives me a sense of old world dignity, but feels very… staged. Curator: Absolutely. Houbraken was a master of capturing not just likeness, but also status. Look at the symbolism: the open book, likely a bible or religious text, signifies Boskoop's vocation and learning, but it also taps into a tradition of knowledge and piety associated with portraits of prominent figures. The drapery in the back alludes to how portraits memorialized prominent members of society, almost like saints. Editor: The drape definitely heightens the sense of importance; he's got a sort of pronouncement gesture with the hand. But it almost makes it cartoonish. It’s that very careful placement, the lettering and architectural frame – are they glorifying him, or just saying, here's another guy? I feel myself questioning his genuine sincerity. It is weird? Curator: Not at all. It raises questions of power and representation inherent in portraiture of that era. He served the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Amsterdam, so he embodies the word in multiple senses. The setting also reinforces that association, because people expect it when they see an engraving of someone in the clergy. It is supposed to make a statement. Editor: It’s a visual performance of power, that's exactly it. It says “reverend man” without having to spell it out. I think, as time goes on, we tend to feel the artificiality of the genre over its intended symbolism. Does it capture this specific man, or does it stand in for a certain type? Curator: The latter is what engravers were tasked to produce at this time in Europe. However, It also taps into the deep vein of Reformation-era portraiture that sought to emphasize the individual's direct relationship with scripture, removing the need for intermediaries. Editor: I guess, in a way, that explains some of its staying power. It might seem dated now, but those visual cues carry so much historical weight. It's a little like holding a conversation with the 18th century, a conversation about faith, and how you visually signify truthfulness. Curator: A somber reminder of faith. And indeed, a window into how societal roles were visually constructed and reinforced back then. Editor: Precisely, a carefully constructed image—it's always fascinating to think about what remains, and what gets lost over time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.