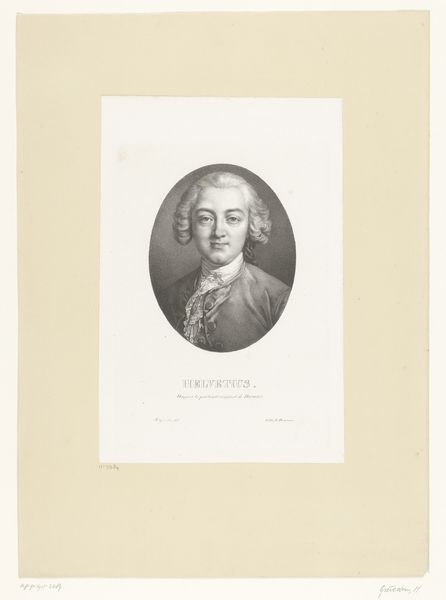

Dimensions: height 259 mm, width 207 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

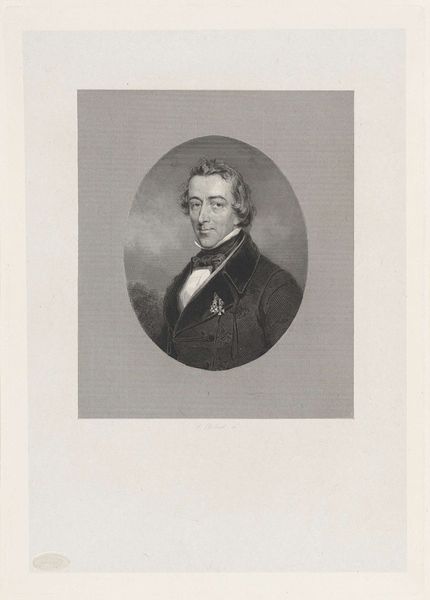

Curator: This is an engraving from 1858, titled "Portret van de predikant Wilhelm Broes," now held here at the Rijksmuseum. The artist is Dirk Jurriaan Sluyter. Editor: My immediate impression is of somber authority. The monochromatic palette emphasizes the sitter’s composed demeanor. It almost feels photographic, with the precision in the lines. Curator: Indeed, the print closely mimics the realism popularized by photography at the time. It depicts Broes in an oval frame, adorned with an order – likely a signifier of his social standing. But what interests me is the engraving itself. The precision suggests the skill involved and the engraver's access to materials; there must have been patronage. Editor: And the choice of print as the medium for portraying a religious figure also signifies how status was replicated and disseminated in mid-19th century Dutch society. Consider the rise of affordable prints, expanding the art market beyond wealthy elites. How does the accessibility influence the perception and impact of his religious message? Curator: That's fascinating. We can investigate further how images such as these supported the establishment. It points toward a democratization, but still controlled and measured through portraits of specific social and religious figureheads. The creation of such pieces was tightly controlled, from the lines employed, and even the type of paper utilized, every aspect adheres to social constructs and access. Editor: Precisely. It brings into the conversation notions about public persona, the social value attached to professions, and the institutional apparatus involved in representing, selling and circulating such prints in Dutch society. Curator: Looking closely, you can appreciate the artistry of engraving – the subtle variations in line thickness. Each element required painstaking work. We can examine and explore these skills. It begs the question of artistic value against the labor-intensive act of production, which must not be forgotten! Editor: Exactly! Viewing it this way helps reveal a bigger historical story, moving past pure aesthetic judgements, highlighting how material art embodies social, and political values of its period. Curator: It brings such a different dimension and expands the meaning beyond the surface impression. Editor: I agree. The portrait isn't only an image of a pastor, but also, the trace of economic structures that allowed it to exist.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.