Copyright: Public domain

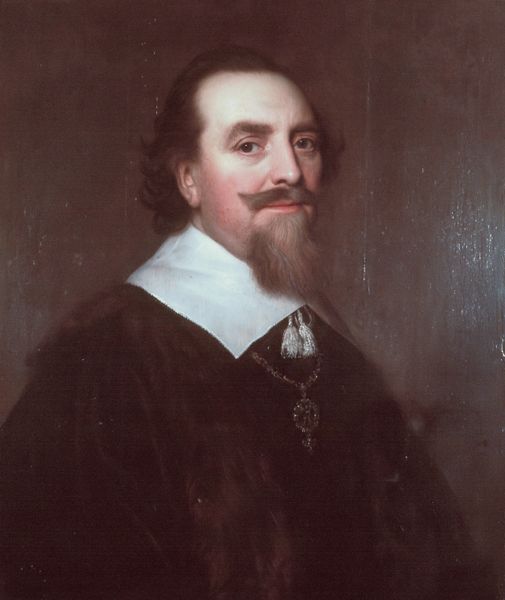

Editor: This is Henryk Rodakowski's "Marshal Jan D. Tarnowski," painted in 1889 with oil. The detail in his clothing seems so tactile. How would you approach interpreting this portrait? Curator: Let's look at this from the standpoint of material production. Rodakowski's meticulous application of oil paint serves not just to depict, but to *produce* status. The very cost of the materials, the artist’s time, speak volumes about Tarnowski's position. Consider the fabrics rendered – velvet, perhaps? Where would those originate, and who labored to create them? Editor: So, it’s not just *of* a wealthy man, but created to show wealth? Curator: Precisely. The very process elevates the subject. Now, think about the commissioning of such a work in 1889. Photography was emerging. What did an oil painting still *do* that photography couldn't? It asserted a tradition, an artisanal skill connected to a longer lineage of power and patronage. Editor: I hadn't thought about photography impacting its function like that! Curator: Exactly! How the materials perform becomes incredibly important. How the labor and process contribute to the social value represented, in the work. Who gets painted and why? The materials don't lie! Editor: This makes me think about all the decisions and hands involved beyond just the artist, like sourcing the paint or preparing the canvas. Thank you for shedding some light on the social factors behind this piece. Curator: Indeed, a true understanding involves questioning the layers of labor, cost, and social implication that constitute art history!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.