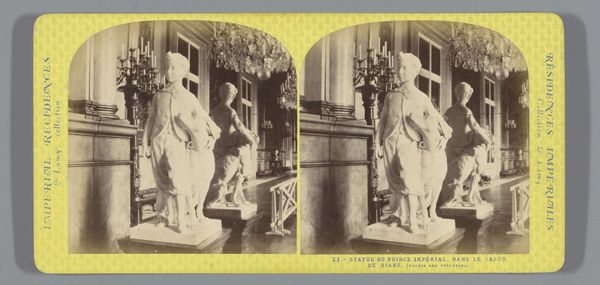

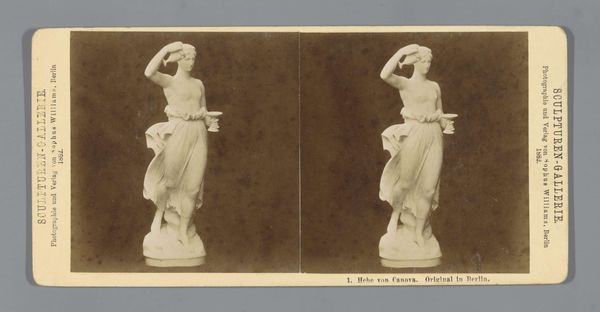

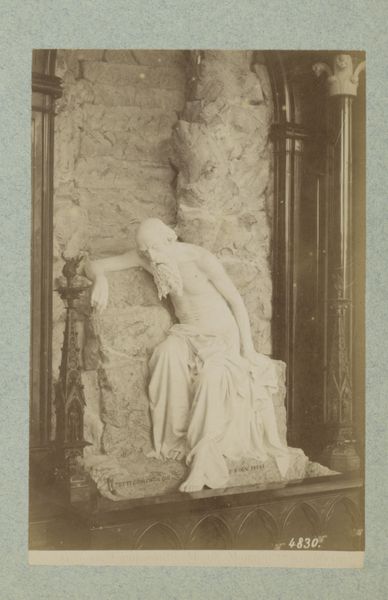

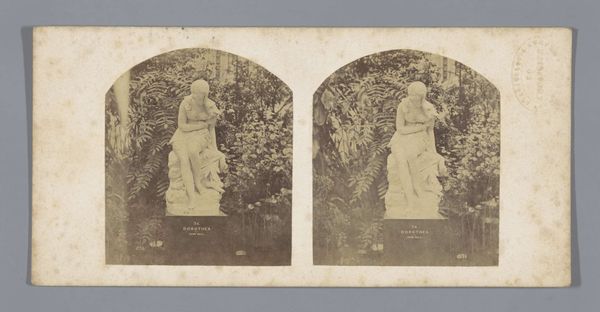

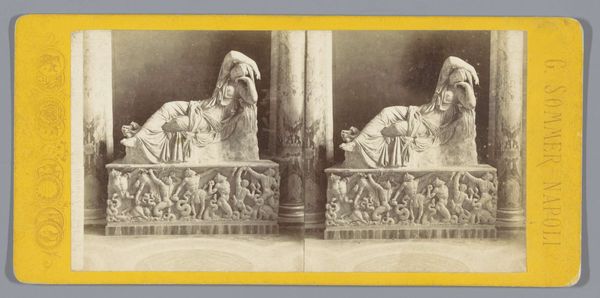

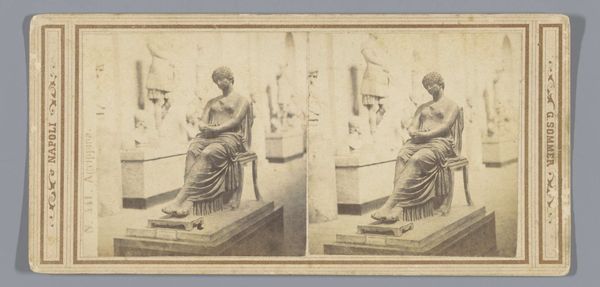

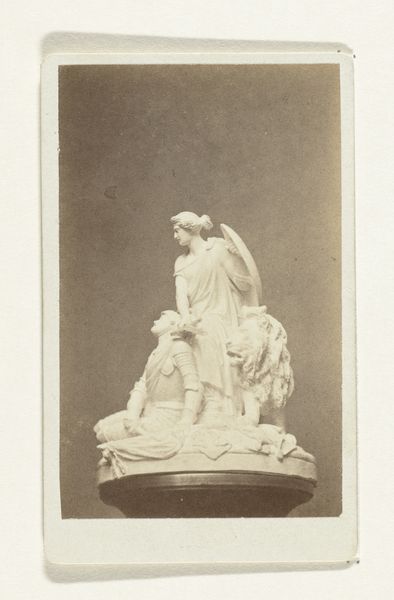

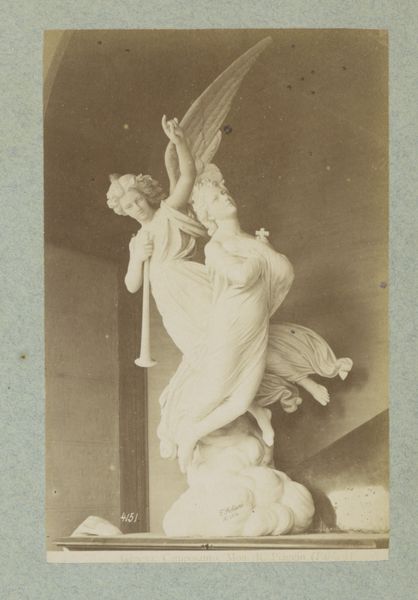

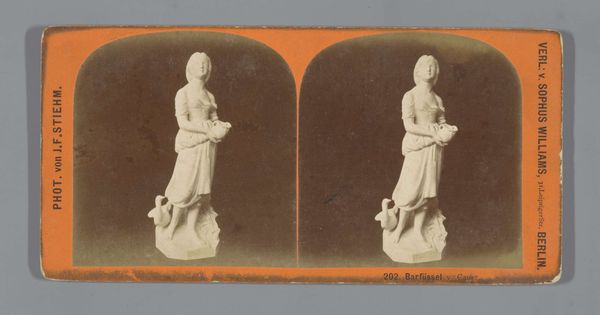

print, photography, sculpture, albumen-print

#

portrait

#

neoclassicism

# print

#

photography

#

sculpture

#

albumen-print

Dimensions: height 86 mm, width 177 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is a stereo photograph titled "Sculptuur van Bacchus in het Orangeriepaleis in Potsdam," taken by Sophus Williams in 1876. It looks like an albumen print of a neoclassical sculpture of Bacchus. I’m struck by how staged the photo seems, almost like a miniature theater set. How do you interpret its relationship to Neoclassicism, considering the social context of the time? Curator: That's a keen observation. Neoclassicism, especially in the 19th century, often served as a visual language of power, harking back to the perceived order and reason of ancient Greece and Rome. Photography like this allowed the broader dissemination of these ideals. Think about who commissioned and consumed images like these. Who was the intended audience, and what message were they meant to take away about culture and taste? Editor: It seems to me that showcasing classical sculpture in photography could democratize access to art, but the cost and availability of photographs must have limited access. So who exactly did see photographs like this, and how did it shape their perception of art? Curator: Exactly. While photography was more accessible than owning a sculpture, it was still largely a privilege. The middle and upper classes would have used images like these as a way to align themselves with perceived ideals, visually cementing social hierarchies. The ‘truth’ of photography combined with the grandeur of Neoclassicism offered a potent way to create and reinforce notions of social order and cultural legitimacy. But let’s consider also the photographer, Sophus Williams, who made this for commercial distribution. Editor: That makes me think about how museums shape public taste and understanding. Williams, by framing the sculpture this way, directs viewers toward certain ideals. Curator: Precisely! Images like these became building blocks for the construction of national identity and cultural capital, shaping how people viewed both the past and their present. We see the politics of imagery in play. Editor: I hadn't considered how photographic prints contributed to social and cultural ideas at the time. Curator: And by studying these photographs as historical objects, we gain a richer understanding of how art functioned within a specific society. What you initially saw as ‘staged’ can now be understood as a very purposeful construct with historical implications.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.