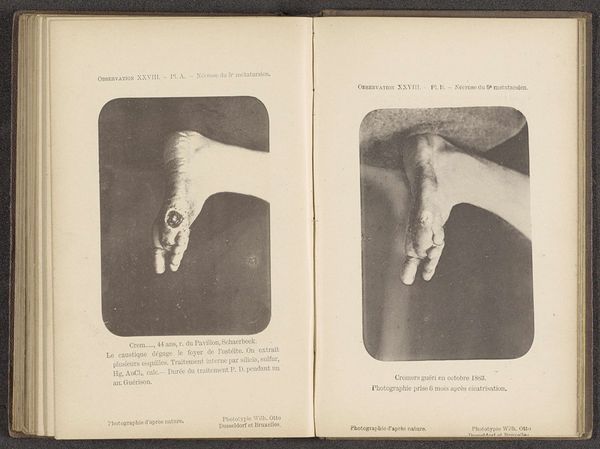

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

book binding

#

homemade paper

#

paper non-digital material

#

paperlike

#

sketch book

#

personal journal design

#

photography

#

personal sketchbook

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

publication mockup

#

letter paper

#

realism

Dimensions: height 133 mm, width 87 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

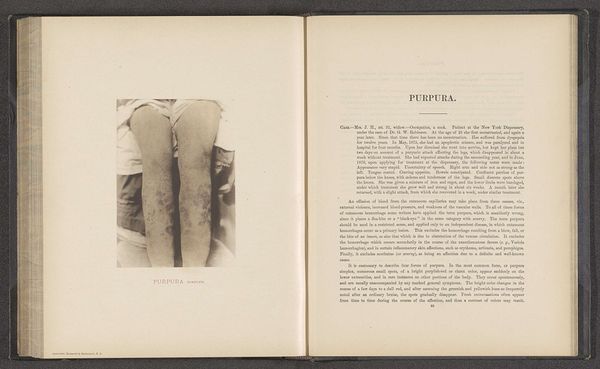

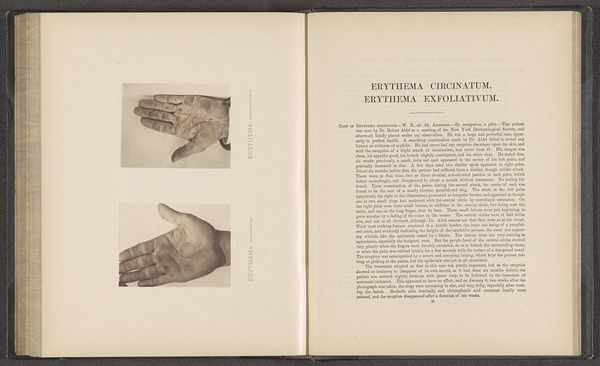

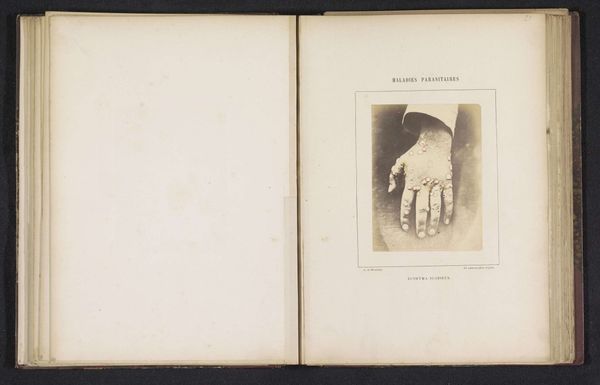

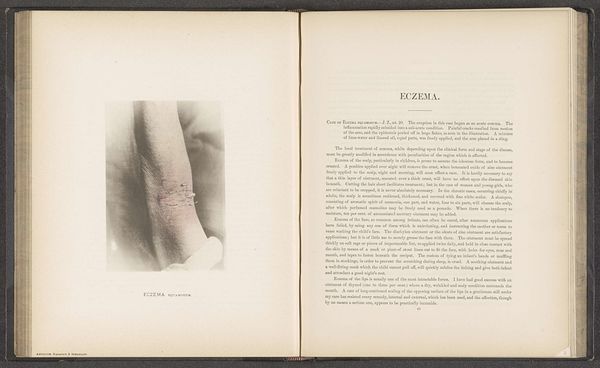

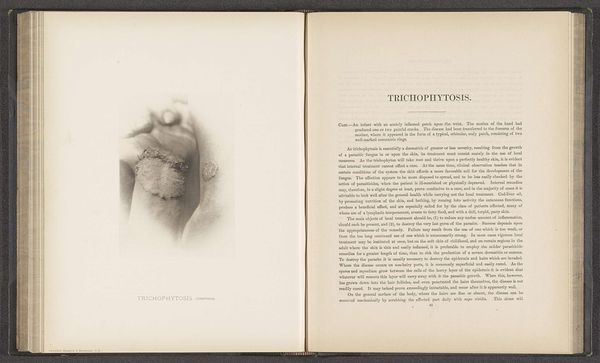

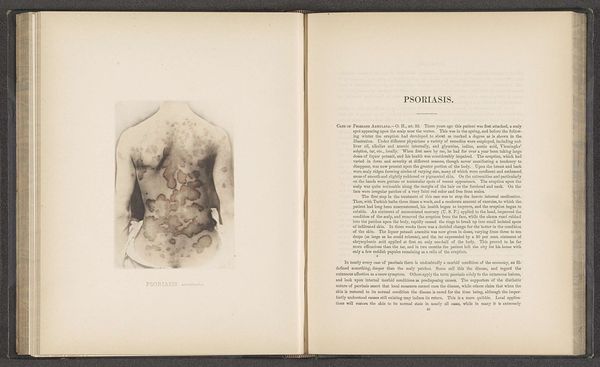

Curator: We’re looking at "Patiënt lijdend aan de huidziekte 'eczema palmae'," which translates to "Patient suffering from the skin disease 'eczema palmae.'" This gelatin-silver print is from before 1881, and the photographer is anonymous. Editor: Well, it's striking. There’s a visceral honesty about the image. It's a stark, monochrome study of a hand afflicted by eczema. Immediately, I feel empathy—a physical echo almost—resonating with the discomfort it must represent. Curator: These types of medical photographs from this era, often found bound in medical texts and journals, served a dual purpose. They were scientific documentation, intended to classify and understand disease, but they also inadvertently reflect the social dimensions of illness, right? Who had access to care, whose suffering was deemed worthy of record. Editor: Exactly. It makes you consider who the intended audience was. Was it strictly for the clinical eye, or were there other layers of meaning, like warnings or perhaps even curiosities, at play? It's clinical, yet deeply human. I’m stuck by its candor, its almost intrusive observation. There's no aesthetic buffer here; we’re faced with something raw and exposed. The fragility is quite affecting. Curator: It speaks to the power dynamics inherent in the clinical gaze and touches on contemporary discussions about representation, privacy, and medical ethics. There is something of a parallel in artmaking and this photograph, wouldn't you say? It can challenge prevailing norms on what it means to look and to document. Editor: You're right, a stark paradox arises when one gazes upon suffering preserved with meticulous care. One has to think of where is our responsibility as audience, viewer, to confront that head-on? In art as in medicine, such reflections are vital to avoid simple objectification. Curator: Precisely, its place in history allows us a glimpse into a different era of medical understanding, reminding us of the complexities of both progress and ethics in visual culture. Editor: I see that; it’s much more than just a clinical image; it is also a quiet, reflective commentary.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.