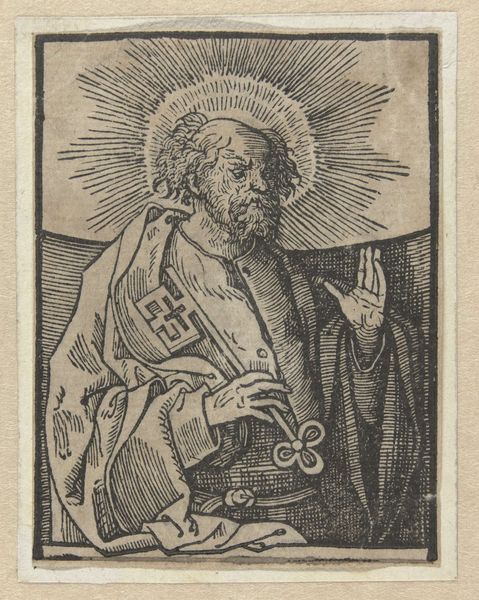

Judas Thaddaeus, from Christ and the Apostles 1514

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, engraving

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

pen illustration

#

figuration

#

11_renaissance

#

northern-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: Sheet: 8 3/16 × 5 3/8 in. (20.8 × 13.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

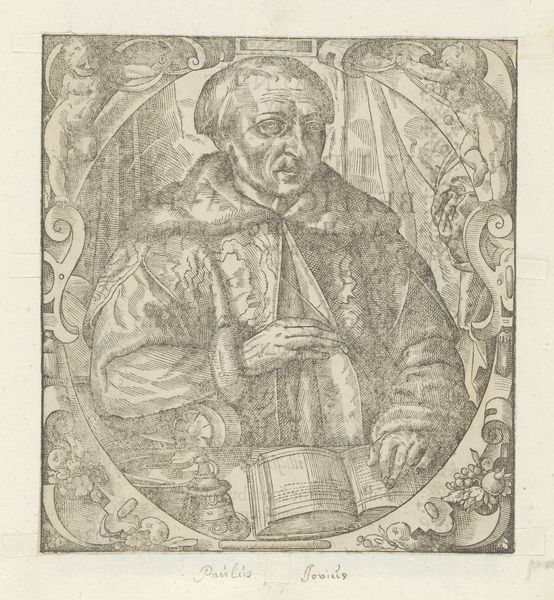

Curator: Here we have Jacob Cornelisz van Oostsanen’s "Judas Thaddaeus, from Christ and the Apostles," an engraving dating back to 1514. Look at the details rendered solely with line! Editor: It strikes me as remarkably earnest. The lines around his eyes and the set of his mouth… he has the weight of the world in those furrows. Curator: Note the symbolic objects, as Judas Thaddaeus, or Jude, is frequently shown with. In this print, he holds a book representing his authorship of the Epistle of Jude and gestures with his hand as if in discourse. Editor: Considering the Northern Renaissance's cultural anxieties, I wonder about the impact of images of apostles on those grappling with the era's religious upheavals? Visual representations helped spread particular interpretations... sometimes deliberately partisan. Curator: Indeed. Images played a crucial role in the Reformation’s debates. Observe the halo surrounding Jude’s head—a clear symbol of sanctity and divine grace, rendered with these meticulously engraved lines that almost vibrate with light. Even the ornate architectural frame emphasizes the power and importance of the central figure. Editor: Right, but the cherubic figures supporting the architectural framework seem... saccharine, even cartoonish, almost undermining the gravitas the artist seems to be aiming for with Jude's direct gaze. Perhaps an appeal to a broader audience? A way to make weighty religious content more digestible? Curator: It certainly blends Renaissance humanism with its religious themes. These "putti" add a layer of classical reference, linking Jude to a longer lineage of wisdom. Plus, within that symbolic structure, consider the role of printed images themselves in spreading ideas, a sort of mirroring. Editor: You are right. This interplay reminds me that early printed portraits not only depicted figures but actively constructed and disseminated narratives about them. That means assessing how these visuals bolstered established authority... or inadvertently subverted it. Curator: Looking at the density of line and intricacy achieved with the engraving medium I keep imagining Oostsanen hunched over a plate in the dim light of his workshop meticulously crafting each mark, and reflecting about this saint’s attributes. Editor: Thinking of that, perhaps understanding how historical power dynamics and artistic choices converge enriches how we interact with images today, because of that cultural continuity, maybe, right?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.