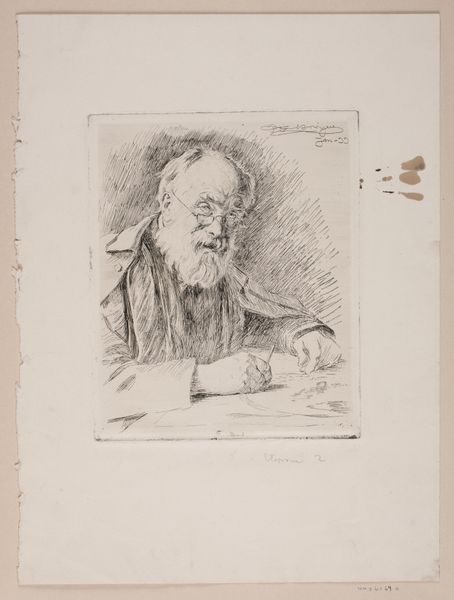

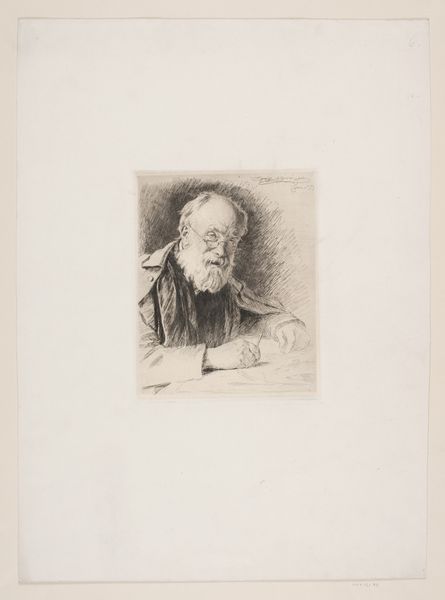

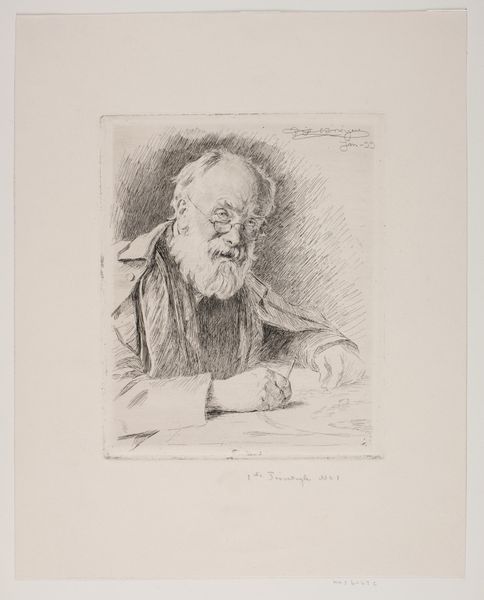

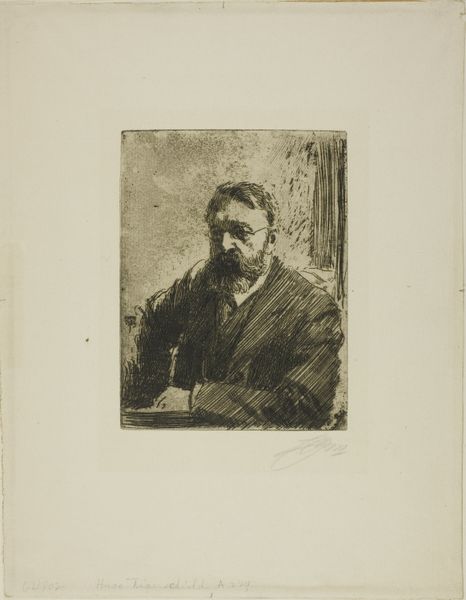

print, etching, paper

#

portrait

#

toned paper

# print

#

etching

#

paper

#

realism

Dimensions: height 527 mm, width 457 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

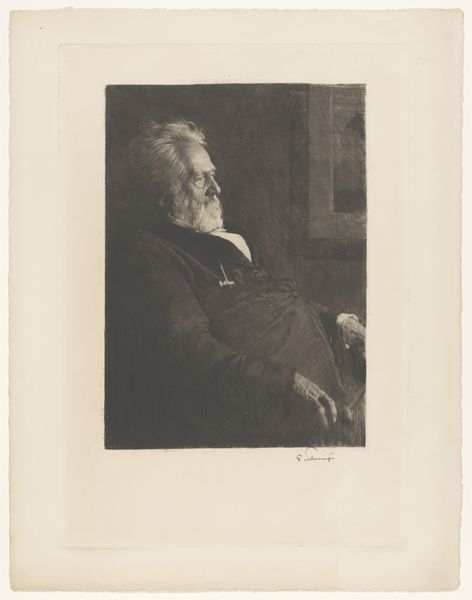

Editor: This is "Portret van Theodor Leschetizky" by Ferdinand Schmutzer, an etching on paper that was created sometime between 1880 and 1920. It's a very traditional portrait. I find the subject's expression rather intense. What's your interpretation of this work? Curator: What stands out for me is how this portrait operates within a specific cultural moment. Late 19th, early 20th century Europe was grappling with rapid social changes, shifts in class structures, and burgeoning national identities. Here, we see Theodor Leschetizky, a renowned piano teacher, elevated almost to the status of a cultural icon through this very medium, print. Consider how easily prints could circulate at the time compared to paintings, making his image accessible to a broader public. Who was included and excluded from that "public"? Editor: That's an interesting point. I hadn't considered the social impact of printmaking itself. It really does democratize access to art. I suppose a painting of him would have been much more exclusive. Curator: Exactly. And beyond just accessibility, how might this widespread distribution shape perceptions of genius, authorship, and fame itself? Look at his pose – the gaze, the hand holding what appears to be a writing instrument – are we invited to see him as a performer, a composer, or a pedagogue? How does this construction serve certain narratives about artistry, or even whiteness, during that era? Editor: So, you're saying that even seemingly straightforward portraits can reinforce existing power dynamics. Is the stack of paper behind him suggestive of his authority as well? Curator: Precisely. Those papers are almost like a symbol of knowledge and achievement. What do we take for granted when viewing such a portrait today, disconnected as we are from the nuances of its original context? What canons are created or reinforced when such figures as Leschetizky become recognizable cultural images? Editor: It's made me realize how important it is to look beyond the surface of a work and understand the social and historical factors that shaped both its creation and its reception. I’m left wondering whose portraits *weren’t* made or widely circulated. Curator: Exactly, and by asking those questions, we can start to deconstruct those historical power structures.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.