tempera, painting, oil-paint, fresco

#

portrait

#

allegory

#

narrative-art

#

tempera

#

painting

#

prophet

#

oil-paint

#

figuration

#

fresco

#

oil painting

#

christianity

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

Copyright: Public domain

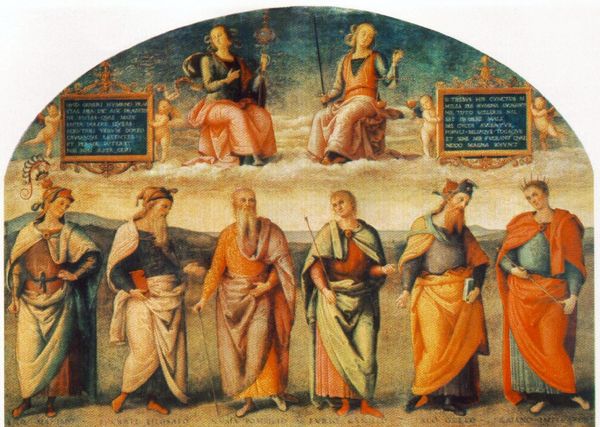

Editor: Here we have "The Almighty with Prophets and Sibyls" made around 1500 by Pietro Perugino. I'm really struck by how the fresco's made, it feels so flat, especially with those almost cartoonish cherubs floating above. How would you unpack this artwork, especially its historical and social making? Curator: Well, let's start with the fresco technique itself. It's pigment applied to wet plaster. Think about that labor - the constant need to prepare and apply fresh plaster, the speed required to paint before it dries. That process reflects a system of patronage and workshop production; time is money for everyone involved. Does that immediate, physical act change how you see the final piece, now that you know of the speed that was required? Editor: It does! It feels less "divinely inspired" and more like a well-oiled workshop cranking out religious imagery. The materials themselves also become interesting: Where did the pigments come from? Who mined them, processed them, and sold them to the artist's workshop? Curator: Exactly. The blues, for instance – are they ultramarine, derived from costly lapis lazuli and shipped from afar? If so, their use indicates a patron willing to spend lavishly, embedding social status into the artwork through materiality. Consider also the relationship between the 'high art' of fresco painting and the craft traditions involved in preparing plaster and grinding pigments. What distinctions can be drawn there? Editor: I see, so it challenges the idea of the artist as a solitary genius, highlighting instead a network of labor and trade that makes the artwork possible. Plus the economics that drove this whole operation. Curator: Precisely. By focusing on these elements of the production, we move beyond just appreciating the image to understanding its place in the material and social world of Renaissance Italy. We also open up a way of thinking about how the work's materiality itself communicates values. What have you gotten out of this thinking in a materialist way? Editor: Thinking this way really pulls back the curtain, revealing so much more beyond just what’s depicted. Now I see it not just as a religious scene, but also as a reflection of the economic and social dynamics of its time.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.