Studies van een hek, een poort en een landschap met windmolen 1855

0:00

0:00

johanconradgreive

Rijksmuseum

#

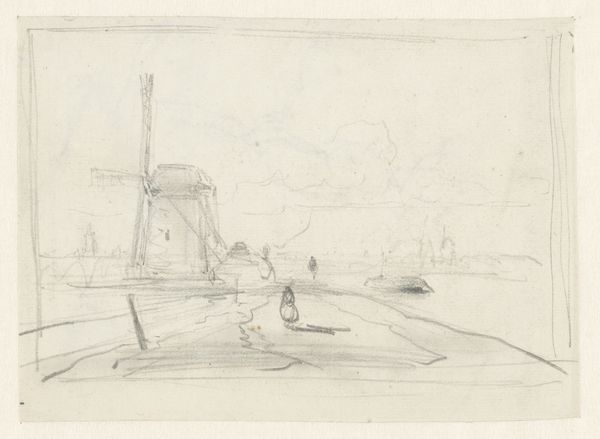

light pencil work

#

quirky sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

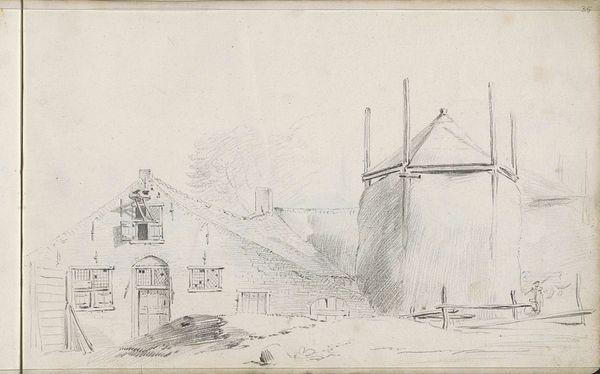

incomplete sketchy

#

personal sketchbook

#

sketchwork

#

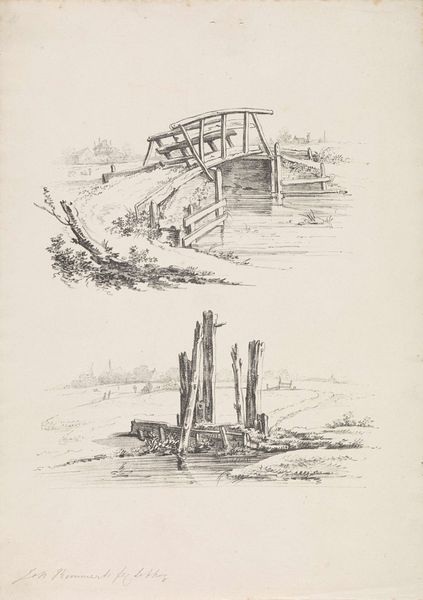

pen-ink sketch

#

sketchbook drawing

#

sketchbook art

#

initial sketch

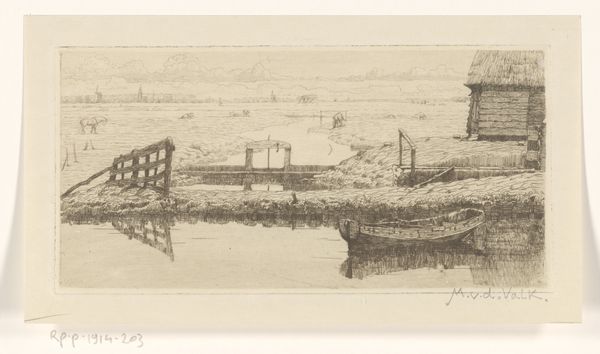

Dimensions: height 183 mm, width 271 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

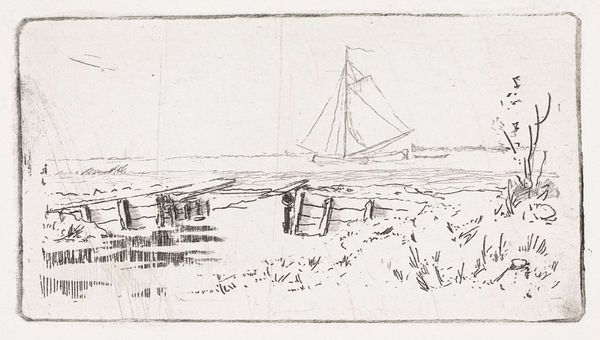

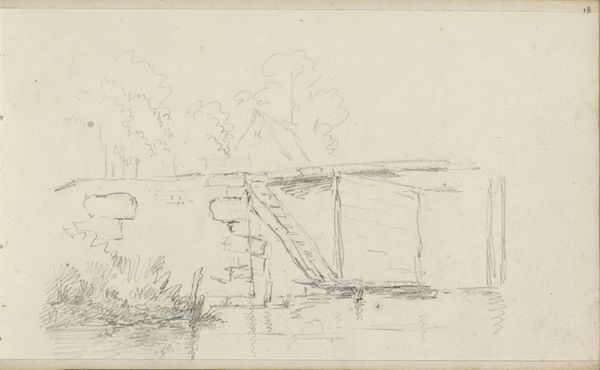

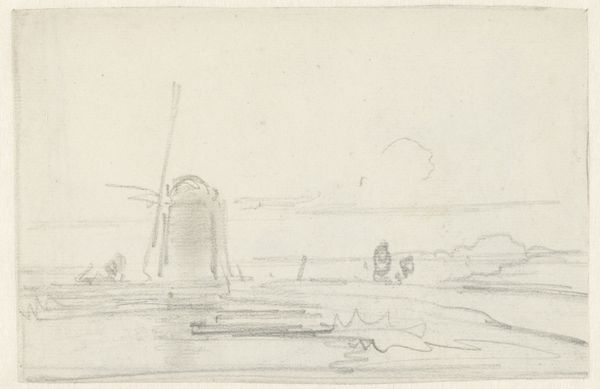

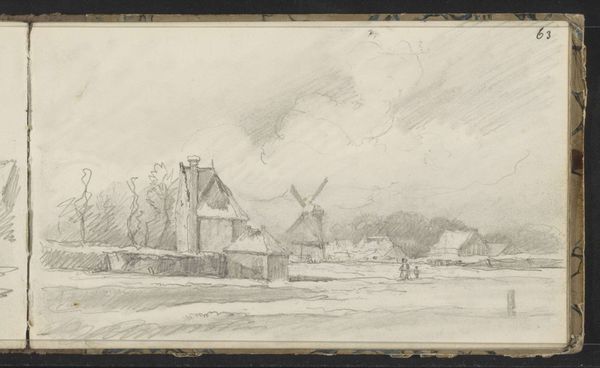

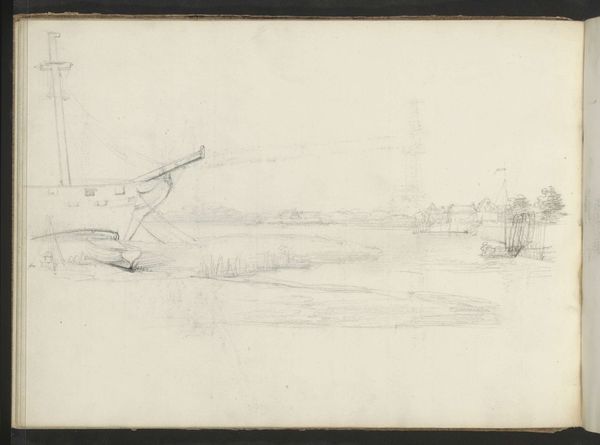

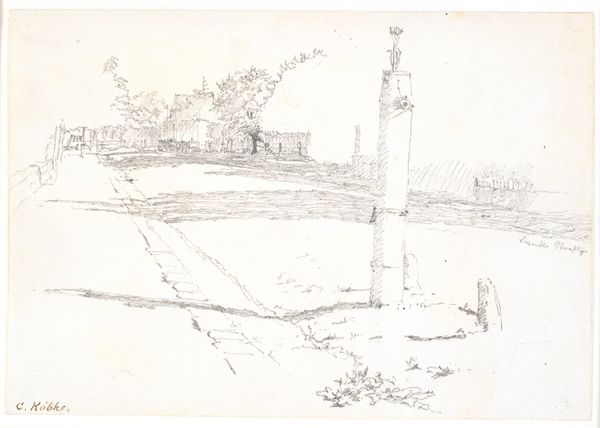

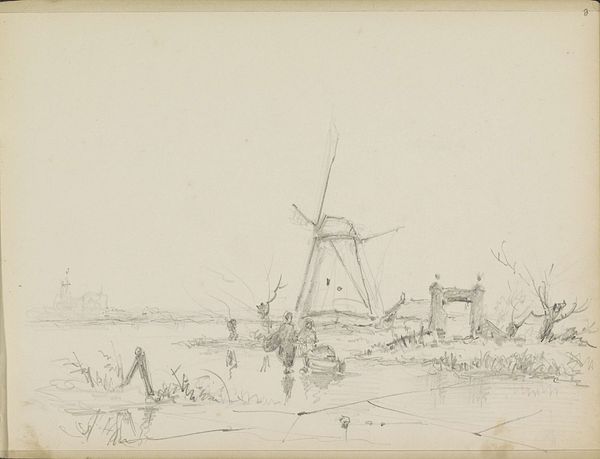

Curator: Immediately, I'm struck by the quiet simplicity, almost a melancholy in the greyscale. It feels like a memory fading. Editor: Today we're looking at "Studies van een hek, een poort en een landschap met windmolen", a pencil sketch completed in 1855 by Johan Conrad Greive, now held at the Rijksmuseum. For me, it immediately highlights questions about land use and ownership, particularly within the context of 19th-century Dutch society. Curator: Definitely, and you see how economically he uses the pencil – it speaks to the material constraints perhaps. Not a lavish work, is it? Editor: The sketch-like quality certainly invites speculation. Was this preparatory? Or was the point in depicting those fences and gates was to ask "who gets to pass and who's excluded?” The windmill too implies human intervention, changing the landscape. Curator: And I find the incomplete, almost utilitarian depiction of the windmill fascinating, it really brings to the fore the artistic decisions. The way he renders form is so basic but complete for all purposes; it’s interesting that he doesn’t bother with the sails. He captures its essence but refuses to glorify it. Editor: The gate's inclusion, especially positioned higher than the viewer, suggests power, privilege even. Looking at it in terms of the period, with increasing urbanization, this could signal anxiety about lost access, about the privatization of previously communal spaces. Curator: Perhaps Greive is highlighting the function of boundaries, the very real social and economic divisions embedded within what seems a very innocuous scene. And it’s all here – raw, unprocessed, honest, in the mark-making itself. Editor: Precisely. It is not merely a picturesque landscape. Greive is speaking about societal structure and hierarchies. His act of observing and recording becomes an active critique, asking viewers to consider who benefits and who's left out in this "idyllic" world. It's not just seeing but revealing underlying structures of power and social stratification. Curator: An insight I wouldn't have necessarily perceived, thank you. I feel I’m coming away having seen not only an artwork but its material consequences. Editor: Absolutely. Context enriches not only art historical perspectives, it hopefully sparks critical engagement.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.