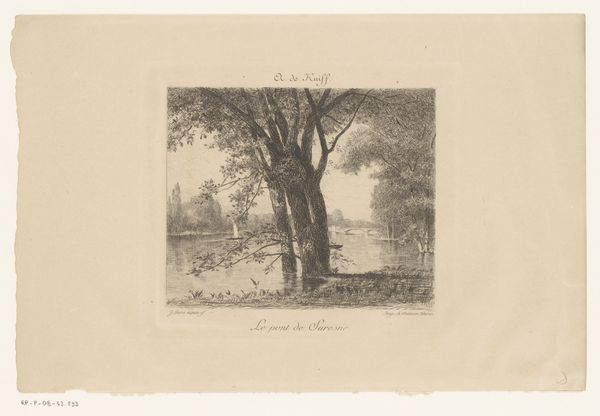

Illustration fra J.Th. Lundbyes billedrulle til H.E. Freunds børn 1848 - 1926

0:00

0:00

drawing, print, etching, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

toned paper

#

ink painting

# print

#

etching

#

incomplete sketchy

#

landscape

#

etching

#

paper

#

ink

#

sketchbook art

Dimensions: 114 mm (height) x 152 mm (width) (bladmaal)

Curator: Let's turn our attention to this etching. It's entitled "Illustration fra J.Th. Lundbyes billedrulle til H.E. Freunds børn," made between 1848 and 1926 by Waldemar Böhme. Editor: My initial impression is of a quiet, almost melancholy scene. The stark contrast of the ink on the toned paper lends it a somewhat somber, reflective quality. Curator: It’s intriguing to consider this work as an illustration for children. On one level, it reflects a very romantic vision of nature, doesn’t it? One that would impart values onto young viewers of their time period, a sense of place. It connects them to a historical landscape and their belonging to it. But beyond the beautiful scenery, who is included, who is not? What values about Danishness are imparted in such artwork, consciously or subconsciously? Editor: Absolutely. Considering the period it was made, think of the production itself: etching as a technique relies heavily on skill and labor. The materiality—the paper, the ink, the press—they speak to a particular mode of production and consumption of imagery. What's fascinating is the blend of artisanal skill with the nascent industrialization of image-making during that time. Curator: It pushes us to consider Böhme’s intentions. Is this merely a pastoral scene meant for aesthetic consumption? Or is it engaging with larger socio-political themes of his day—land ownership, perhaps, or even early environmentalism? Who was able to access this landscape and this narrative of childhood at the time? What statements does the imagery makes about land use, accessibility and privilege? Editor: I think you’re right, there is that sense of a tamed landscape for consumption. Looking closely, one is reminded that each delicate line is deliberate, repeated and reliant on skilled labor. There's labor both in the artist's hand and, presumably, in the eventual production of the print. What were the costs of production at this time, and to what economic level was it accessible? Curator: Seeing the interplay of nature and representation through both of our lenses, what stands out to you as especially relevant today? Editor: For me, it’s that persistent tension between the artistic labor involved and the way nature becomes a product that is consumed, reproduced, distributed, as it was in Böhme's time and even more so in ours. Curator: I concur. By reflecting on these overlooked stories, we find a much deeper engagement with nature and, as we recognize those often marginalized elements, it enhances our appreciation of art’s complexities in social and historical perspectives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.