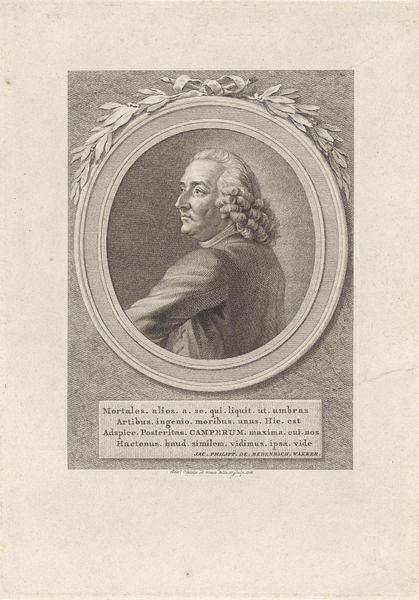

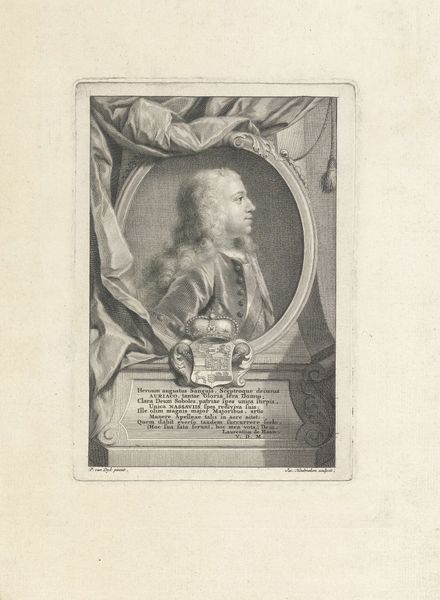

Dimensions: height 205 mm, width 130 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, we’re looking at "Portret van François de Chennevières," a 1770 engraving by Etienne Ficquet. It’s got that old-timey feel, you know? Very Baroque. What strikes me is the level of detail Ficquet achieved with this printmaking process. What stands out to you when you look at it? Curator: Immediately, I consider the labour and materials involved. Engraving, particularly at this level of refinement, was incredibly time-consuming, demanding specialized skills and tools. Consider the social context – prints like these disseminated images of the elite, like Monsieur de Chennevières here, reinforcing social hierarchies. This wasn't just art; it was a commodity. Notice also the aged paper quality. Do you see how that alters the experience from a new, clean version of this engraving? Editor: Right, the aging gives it more of an "antique" flavour now! So, is the quality of the engraving directly tied to the engraver’s status and the patron’s wealth? Curator: Precisely! The finer the work, the greater the expense in materials and time; consequently, access was limited. Engravings acted as currency in a way, showing tangible return on capital. Look closer at the rendering of clothing versus the face - does it suggest anything about Ficquet’s material or economic relationship with his patron, Chennevières? Editor: Hmm… perhaps the greater focus on Chennevières's face meant more time spent there. So it boils down to skilled labour being directed based on importance within a hierarchy... It shifts my perspective to see it that way. Curator: It is interesting how material analysis invites exploration beyond simple aesthetics. Examining art through its production, materiality, and social context allows insight into the conditions of both production and reception.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.