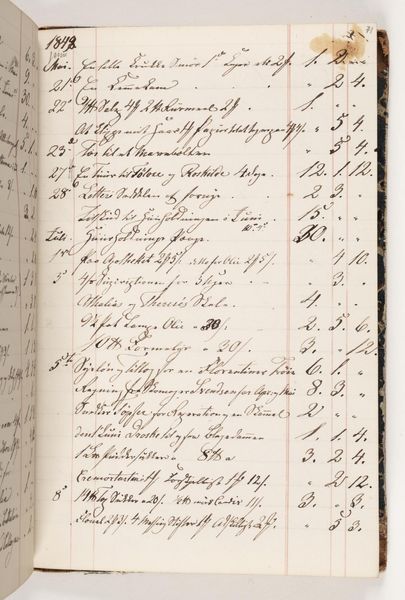

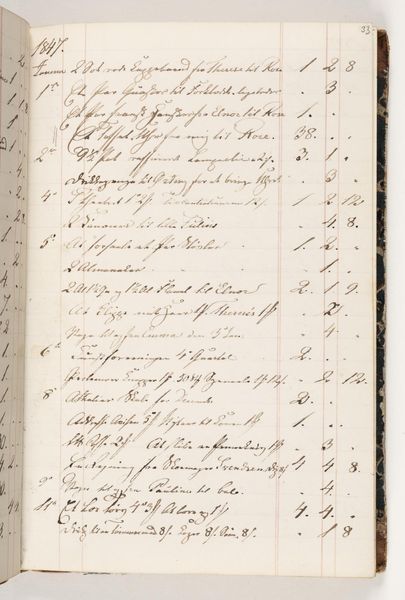

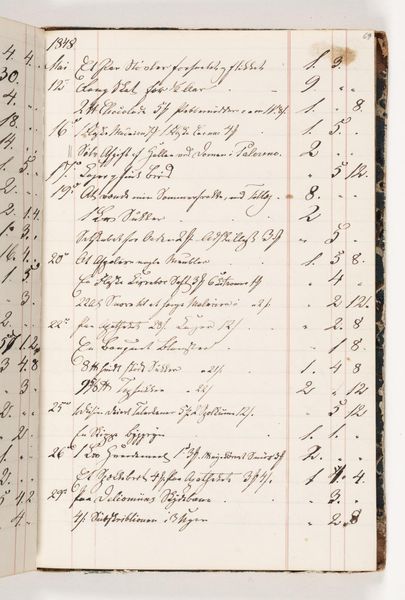

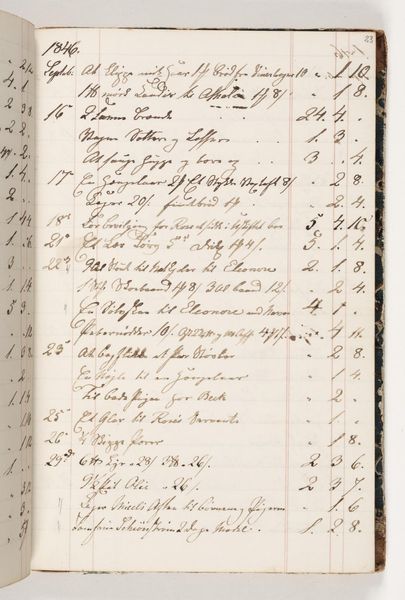

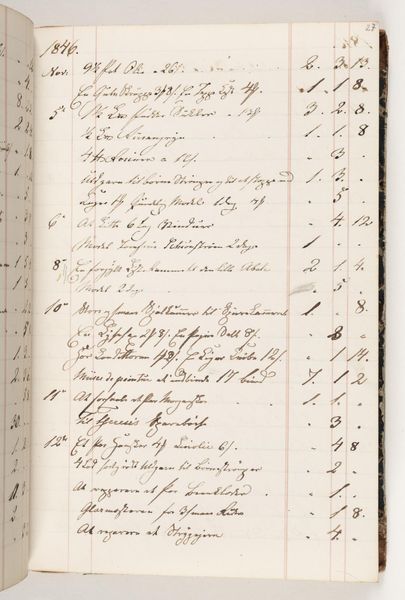

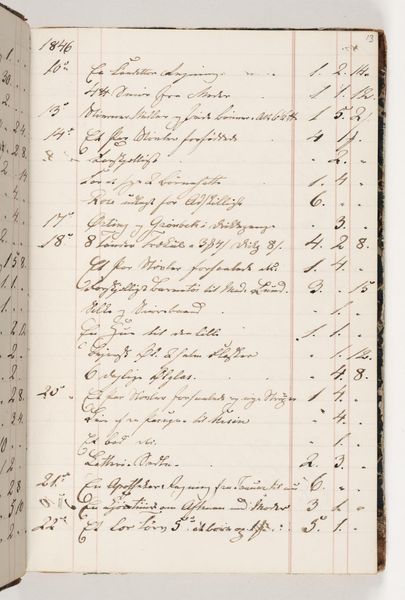

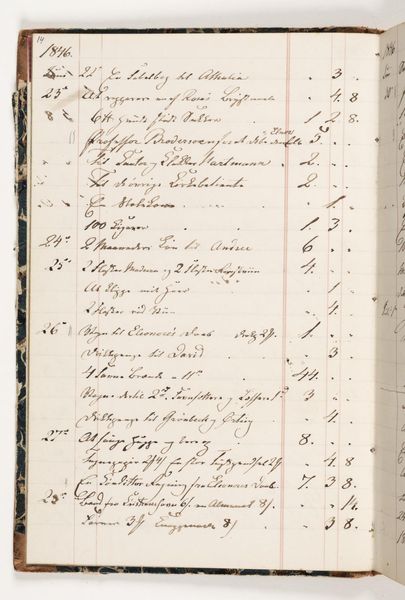

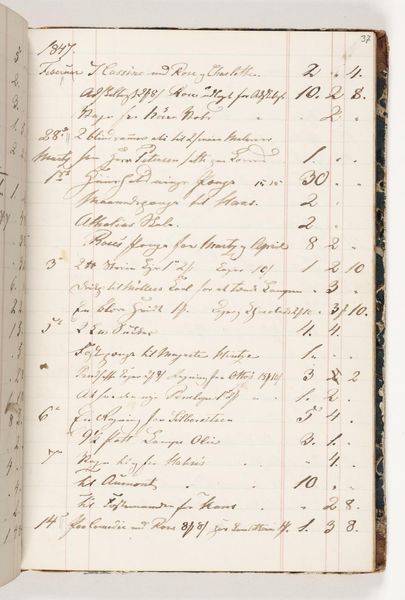

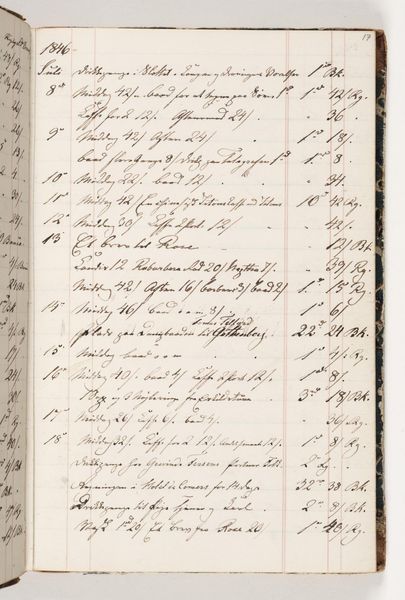

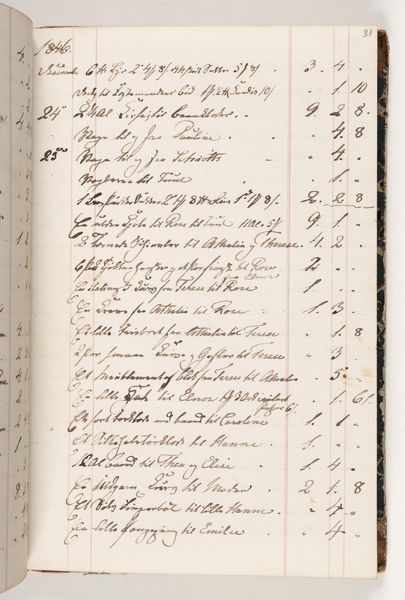

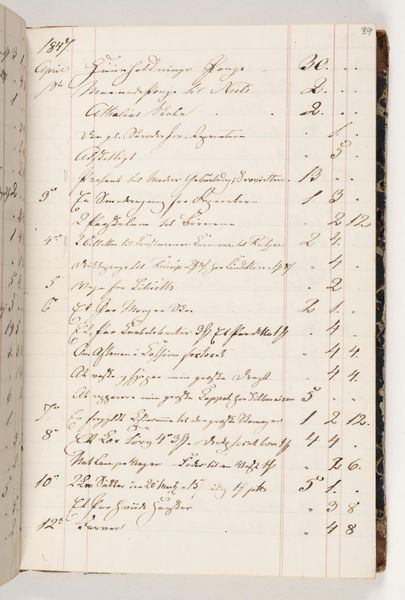

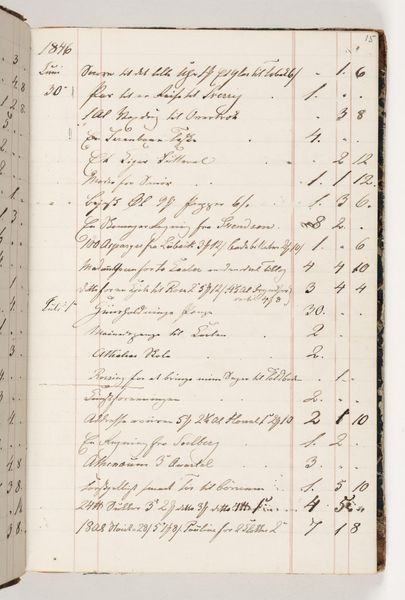

drawing, paper, ink

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: 200 mm (height) x 130 mm (width) (bladmaal)

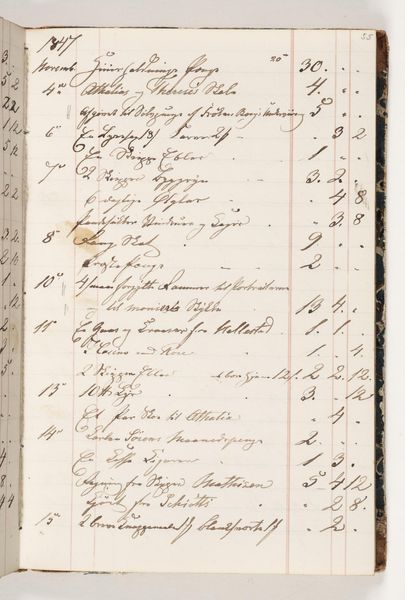

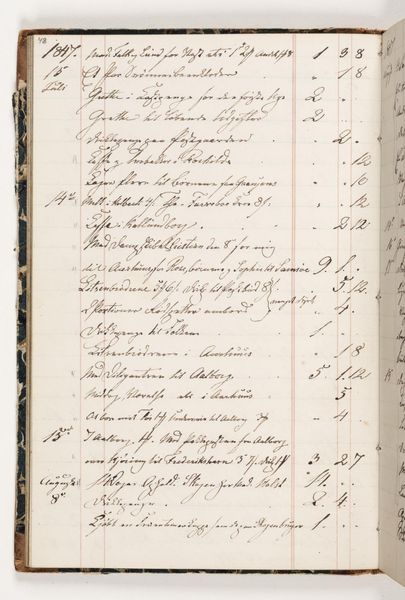

Curator: I find myself drawn to this page—"Regnskab 1848"— an accounting from 1848, executed in ink on paper by Martinus Rørbye. Its austere presence immediately communicates themes of control and accountability, almost in the mode of a history painting. Editor: My immediate impression is one of restrained austerity. The neat columns of script and figures suggest an attempt to impose order on a world in flux. I am, however, curious about who "accounts" for whom and what role accounting plays in wider power structures. Curator: Absolutely, this "history painting" speaks of a cultural drive toward systematic classification. Observe the recurring symbols; this neat ledger embodies order—a societal desire for balance during Denmark’s turbulent transition to constitutional monarchy. Every stroke tells a story about civic duty and meticulous administration! Editor: I do note the inherent contradiction, because there's also something performative about handwriting; this account appears less about accuracy and more about an attempt to give an air of validity. Whose perspective, for instance, is privileged through its inclusion in these records, while others are obscured by its existence? I wonder how such meticulous record-keeping contributed to marginalizing already-vulnerable populations. Curator: It's all there in the script. Consider the symbolic value assigned to legible accounting! Each stroke—with its carefully recorded sum—contributes towards an enduring narrative; it showcases an era dedicated towards constructing a rational world through ordered marks. This is less about marginalization than preservation; after all, the drawing has now allowed it to endure across time... Editor: But even preservation can be a deeply political act. Consider whose stories this ledger chose to safeguard—those who profited or the ones bearing its financial consequences. It might celebrate civic duty for certain figures—for othered groups the balance and "rationality" meant increased policing and governance. Curator: The cultural weight that calligraphy possesses should be remembered; its precise formation offers something deeper rather than arbitrary control—a visualization on morality by mirroring what it considered ethical behavior back again with repeated sums and notations. Editor: I’m left thinking about the unwritten histories—what isn't itemized on these pages is sometimes most reflective about 1848 society and all those silenced then and today. It speaks loudly too—about inequalities which endure. Curator: Well, looking back upon these neat entries gives valuable lessons about cultural memory; how did older perceptions make then before being enshrined for perpetuity? It certainly illuminates the ethical considerations required today!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.