photography

#

portrait

#

charcoal drawing

#

photography

#

19th century

#

genre-painting

#

realism

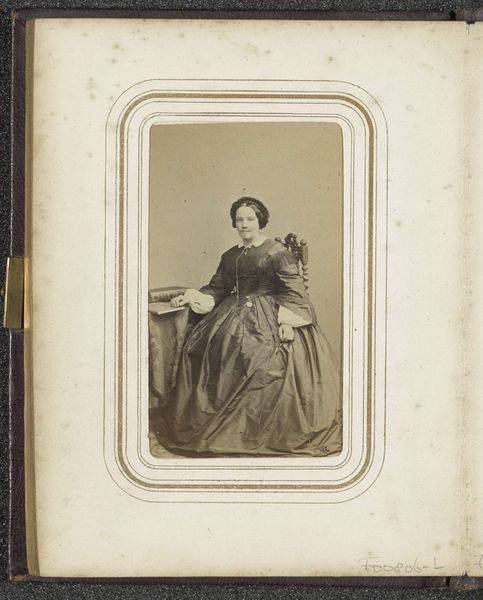

Dimensions: height 85 mm, width 52 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Standing before us is an ambrotype, a photograph called "Portret van een zittende vrouw," dating from somewhere between 1860 and 1894, attributed to Ghémar Frères, held in the collection of the Rijksmuseum. Editor: Oh, the solemn air! It strikes me as terribly formal and reserved. I imagine the sitter must have felt so stifled and rigid. It's a stark contrast to the playful abandon of modern snapshots. Curator: Yes, that air of formality is partly inherent to the genre. It presents an example of early photographic portraiture during a transitional time, a bridge between painted portraiture and the quick snapshots we take for granted. Focus on the structure—notice how the woman's placement within the frame, seated yet almost confrontational, directs our gaze. Editor: I notice, too, the light and shadow play on her face. There's a soft light falling on her. You know, you almost feel a little sorry for her. Imagine sitting perfectly still for…how long would that take in those days, anyway? Curator: Quite a while! And in unflattering lighting no less. But beyond any possible discomfort, this medium of photography offered expanding opportunities of representation to social classes who previously may not have had the chance to immortalize their images for posterity through painting. Her dress, its sheen, the details on the hem all imply status, access. Editor: Status, but at what cost? Trapped in sepia tones and rigid expectations. The woman looks utterly disengaged with her expression hard to read, an artifact from an age when photos felt more like an audit of respectability. Curator: Indeed. Her posture, attire, and expression collectively convey an air of decorum reflective of the late 19th century, perhaps hinting at societal roles or expectations that constrained individual expression during that time. We may find ourselves asking how such early technologies may reflect back the structures that conceived of them in the first place. Editor: Seeing it now, it makes you reflect on how portraits aren’t just about preserving a likeness, they are little time capsules of social etiquette, artistic potential, and unspoken feelings. Each portrait reveals a certain truth and elicits profound questions.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.