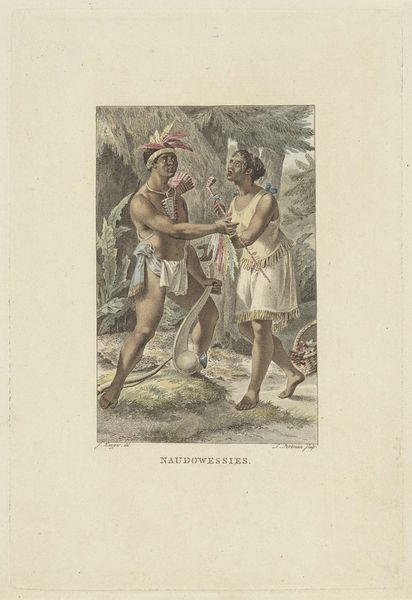

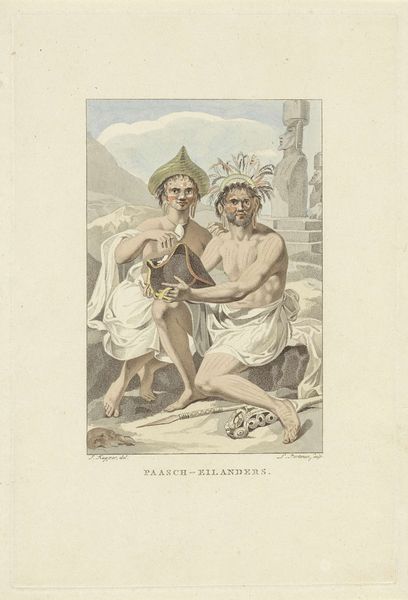

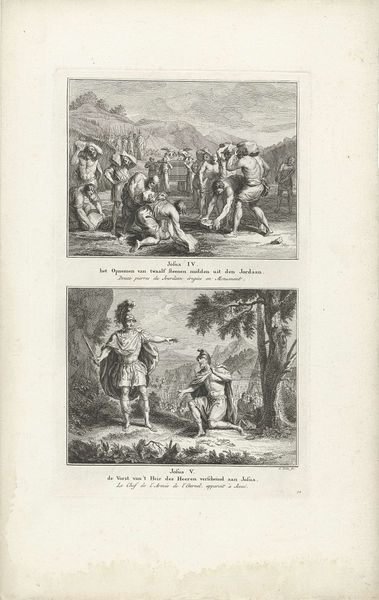

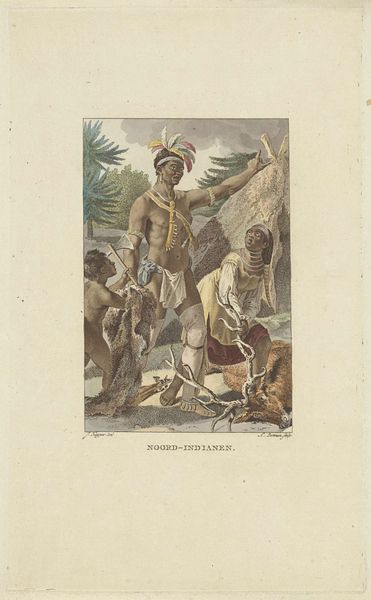

print, engraving

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 247 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Immediately striking is this slightly mournful air of... stillness, almost. Considering the plume of smoke behind them, you might expect tension, but there's a peaceful solemnity in their postures. Editor: Absolutely. And that tranquility exists alongside this visual record from 1803 titled "Bewoners van de Nieuwe Hebriden eilanden (Vanuatu)", or "Inhabitants of the New Hebrides Islands (Vanuatu)", by Ludwig Gottlieb Portman. It's an engraving, a print—a carefully constructed image that deserves our attention. Curator: An engraving, yes, meticulously crafted… There's a dreaminess to it. That volcano looks a bit like a poorly remembered nightmare, softened around the edges. I see this idyllic South Seas scene, but through a filter of European… what? Imagination, maybe? Editor: Definitely imagination—or perhaps more pointedly, Orientalism and Romanticism. This piece very much embodies the colonial gaze of the period. We're presented with these figures who become stand-ins for an entire culture, positioned within this...staged natural backdrop. Note that man playing his flute so indifferently. Curator: Ah, the flute player! It feels performative now that you mention it. The man and woman feel like props in a tableau vivant. What a stage! A distant, erupting volcano; figures arranged like classical statuary, subtly colored with—and I can't get past this—the softness of a pastel drawing… it is kind of disturbing, in a quiet way. Editor: Precisely, and that discomfort is key. We need to ask ourselves: what is the relationship between the artist, his European audience, and these Indigenous people from Vanuatu? The artist uses engraving and portraiture not just to capture their image but to translate them into a visual language that’s palatable to a Western audience—reinforcing pre-existing biases about the “exotic other.” Curator: And reducing people to pretty images. Makes you wonder about all the stories missed. Those figures probably knew so much about their landscape, each other, the very instrument in that man's hands… details Portman wouldn’t have been aware of. A beautiful picture can still hide such painful distortions, I suppose. Editor: Indeed. These romanticized images fueled the colonial project. Analyzing these visuals reminds us to interrogate the power dynamics at play when depicting marginalized communities. Curator: It’s a reminder that art, even something seemingly tranquil, can participate in systems that are far from peaceful. It challenges me to look beyond what's immediately visible, to really question those stories, as you said, that have been erased or glossed over. Editor: Exactly. Art acts as this echo chamber. And it makes me wonder about this image and who looks at it now. Maybe our dialogue might change this old artwork’s current reception for a fraction of our audience.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.