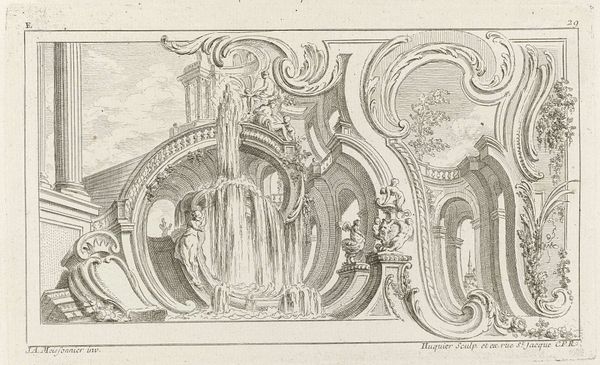

Ornament met trappen naar een terras waarop twee sfinxen 1738 - 1749

0:00

0:00

gabrielhuquier

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving, architecture

#

baroque

# print

#

pen illustration

#

landscape

#

fantasy-art

#

form

#

line

#

decorative-art

#

engraving

#

architecture

Dimensions: height 125 mm, width 220 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving, "Ornament met trappen naar een terras waarop twee sfinxen," roughly translates to "Ornament with steps to a terrace with two sphinxes." It comes to us from Gabriel Huquier, dating back to between 1738 and 1749. Editor: What strikes me immediately is the incredibly ornate framing, the cascading water, and those two stoic sphinxes observing everything from their perches. It feels both serene and performative. Curator: These types of images were used by designers and artisans for inspiration and dissemination of design trends. This print allows us to examine the architectural aspirations and interior design of the elite at the time. Consider the role of the artist in translating the vision into tangible form for the consumption of an emerging public. Editor: I find myself drawn to the contrasting textures. The smoothness of the terrace contrasts against the roughness of what seems like a grotto. The linear quality, typical of engraving, is beautifully employed to create a sense of depth and to separate space within the composition. The use of light, emerging from the shell-like structure also directs the eye. Curator: And what is that eye directed towards, if not the symbols of power and exclusivity so vital to the patrons of these designs? The sphinxes aren't just decorative; they're asserting dominance and acting as silent guardians of wealth and taste, shaping the landscape and dictating its narrative. This was about projecting an image as much as creating a space. Editor: It's a dialogue between power and presentation. The formality and rigidity, especially in the architectural forms, contrast with the organic and flowing frame of leaves. Perhaps an interesting tension there. Curator: Exactly! We can understand how the visual arts were used to express hierarchy and social position during this period and reflect upon how visual language perpetuated the dominant social order. It reminds us that art never exists in a vacuum. Editor: The relationship between what’s represented and how it’s represented, becomes, I think, even more profound after that context is offered. This takes it beyond skillful artistry. Curator: Absolutely. By situating Huquier’s engraving within the design culture of the 18th century, it gains more power as a historical document, providing tangible insight into societal desires. Editor: Agreed. I leave appreciating how visual grammar not only imitates our world, but also reinforces certain societal perspectives through the structure of form itself.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.